A banyan tree in the study’s restored site, where the invasive shrub Lantana camara was removed. Credit: Pooja Choksi

Small-scale restoration efforts that aim to help meet livelihood needs have the potential to contribute to ecological goals in the central Indian landscape, according to a new study published in Restoration Ecology.

The study was led by restoration ecologist Pooja Choksi, a recent graduate of Columbia University, and co-founder of Project Dhvani, a long-term acoustics research collaboration. She and her colleagues used sound recorders to monitor changes in the soundscape after a restoration project in Madhya Pradesh, India. Their findings could have implications for restoration efforts going on around the world.

In 2017, local communities along with the state forest department and the Foundation for Ecological Security began removing an invasive shrub, Lantana camara, from a forest in Mandla district in Madhya Pradesh. The shrub—originally introduced by British colonists in the 1800s—makes it difficult for native trees to sprout, which can be a problem not only for wildlife but for people who depend on the trees for firewood and other products.

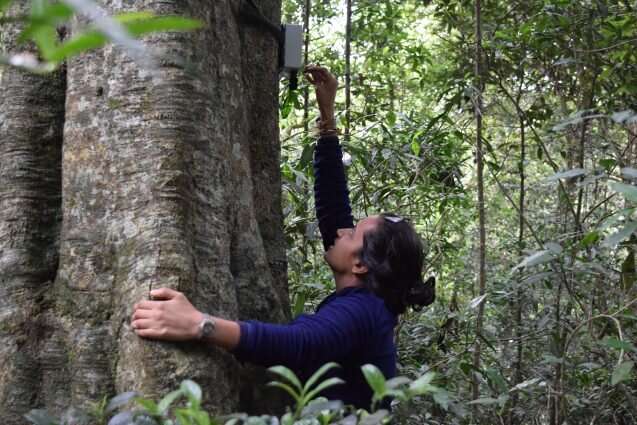

Although the restoration effort in the Mandla district was carried out to benefit the local people, Choksi and her colleagues wanted to see how the effort might affect biodiversity in the area. They tied acoustic recorders to trees in three types of areas: the restored area, forest with naturally low densities of L. camara, and forest with high densities of the invasive shrub. They left the recorders up for two years, and used the data collected to understand the impact of restoration.

Don’t be fooled by its pretty flowers. Lantana camera, originally introduced to India by British colonists in the 1800s, makes it difficult for native trees to sprout. Credit: Pooja Choksi

The researchers found that the restored site had a different community composition of birds—for example, although the total number of bird species was the same across all the sites, the researchers observed that the restored site seemed to have fewer generalist species than the unrestored sites. However, it's not yet clear whether the changes are positive or negative for the ecosystem.

"We simply take this as a sign of change with changes in the habitat," said Choksi. "Given how slowly tropical dry forests regenerate, I think it will take a few more years to see changes in these forests, if any."

The findings suggest that the soundscape was more active at the restoration site, "which is generally a positive sign for ecological health," said Choksi. However, she cautions that this could be a temporary effect of the animals reorganizing after the disruption of the L. camara removal.

-

Pooja Choksi installs an acoustic monitor on a tree. Credit: Sarika Khanwilkar

-

A closer look at one of the acoustic monitoring devices used in the study. Credit: Sarika Khanwilkar

The researchers conclude that small-scale restoration efforts that aim to help meet livelihood needs may contribute small biodiversity benefits over short timescales.

The United Nations has named 2021–2030 the "Decade on Ecosystem Restoration," with the goal of preventing and reversing the degradation of ecosystems on every continent and in every ocean. As a result, there are a large number of ongoing and planned restoration efforts around the world, including in India. With those restoration efforts comes the need to monitor the long-term social and ecological impacts, and the new study shows that measuring soundscapes can be an effective way to do so.

More information: Pooja Choksi et al, Listening for change: quantifying the impact of ecological restoration on soundscapes in a tropical dry forest, Restoration Ecology (2023). DOI: 10.1111/rec.13864

Provided by State of the Planet