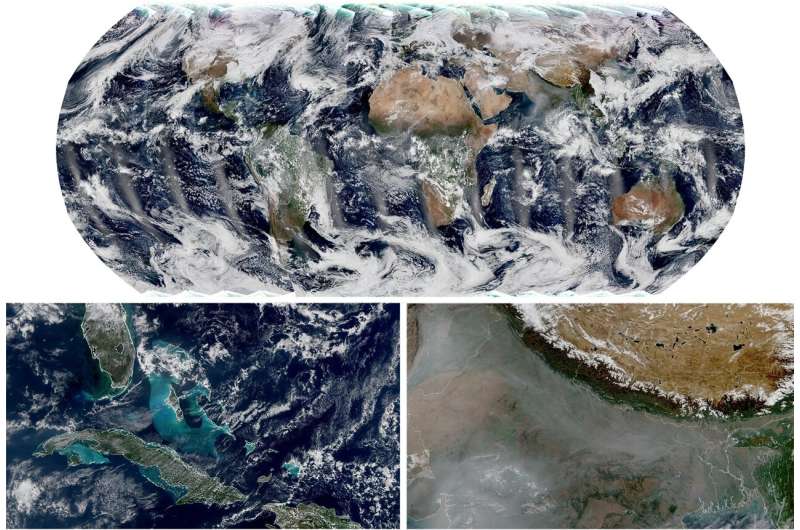

Polar-orbiting satellites capture swaths of data throughout the globe, and observe the entire planet twice each day. The global mosaic, captured by the VIIRS instrument on the recently launched NOAA-21 satellite, is a composite image created from these swaths. Bottom left: This image shows ocean color around the Southern tip of Florida and the Caribbean. Bottom right: In this image over Northern India, you can see smog from prescribed agricultural burns, and the Himalayas and Tibetan plateau to the North. Credit: NOAA STAR VIIRS Imagery Team

Bright blue water in the Caribbean Sea and smog in Northern India appear in the first global image produced with data from NOAA-21's VIIRS instrument.

The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instrument on NOAA-21 began collecting Earth science data on Dec. 5 as the satellite passed over the East Coast of the United States. Data for the global image was collected over a period of 24 hours between Dec. 5 and 6. This came three weeks after NASA launched the NOAA-21 satellite from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California on Nov. 10, 2022.

The VIIRS instrument—which also flies on the NOAA-20 and the NASA/NOAA Suomi-NPP satellites—provides global measurements of the atmosphere, land, and oceans. It was built by Raytheon Intelligence & Space in El Segundo, California.

"VIIRS serves so many disciplines, it's an absolutely critical set of measurements," said Dr. James Gleason, NASA project scientist for the JPSS Flight Project. "VIIRS provides many different data products that are used by scientists in unrelated fields, from agricultural economists trying to do crop forecasts, to air quality scientists forecasting where wildfire smoke will be, to disaster support teams who count night lights to understand the impact of a disaster."

Over the oceans, VIIRS measures sea surface temperature, a metric that's important for monitoring hurricane formation. It also measures ocean color, which helps scientists monitor phytoplankton activity, a key indicator of ocean ecology and marine health.

"The turquoise color that's visible around Cuba and the Bahamas in the bottom-left image above comes from sediment in the shallow waters around the continental shelf," said NOAA's Dr. Satya Kalluri, Joint Polar Satellite System program scientist.

Over land, VIIRS can detect and measure wildfires, droughts and floods, and its data can be used to track the thickness and movement of wildfire smoke. The bottom-right image above shows haze and smog over Northern India that is likely due to agricultural burning. The snow-capped Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau are also visible to the north.

One of the unique features of VIIRS is its Day-Night Band, which captures images of lights at night, including city lights, lightning, auroras and lights from ships and fires. And one of its most important uses is imagery over Alaska, Dr. Kalluri said. This is because these satellites, which orbit the Earth from the North pole to the South pole, fly directly over the Arctic several times a day.

The instrument also generates critical environmental products on snow and ice cover, clouds, fog, aerosols and dust, and the health of the world's crops.

This "first light" image comes two weeks after the first image from the satellite's Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder (ATMS) was released. The satellite, known as JPSS-2 during the build and launch, was officially renamed NOAA-21 after launch, following NOAA's naming conventions for polar orbiting satellites.

"We had two VIIRS on orbit, and now we've got three," Dr. Gleason said. "We launch multiple weather satellites to make doubly and now triply sure we always have one going. Space is a dangerous environment. Stuff happens and you can lose an instrument or a satellite, but we cannot lose the data. It's too important, to too many people."

Provided by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center