'Non-essential' building block proves vital to a healthy protein diet

A "non-essential" amino acid—so-called because the body can make it from other nutrients—can act as a nutritional cue to guide the body's responses to a low-protein diet, a RIKEN-led team has found in a study on fruit fly larvae. If a similar control mechanism operates in mammals, it may be possible to use it to control appetite.

To help us decide whether to chow down on another helping of beef or fish, our brains have evolved mechanisms for sensing changes in protein building blocks in the body and adjusting the intake of protein-rich foods accordingly. Researchers had long assumed this process relied only on those building blocks, known as amino acids, that the body cannot naturally produce on its own.

But now, a RIKEN-led study has found that is not always the case. "We've discovered a new mechanism of sensing and adaptation to dietary protein scarcity," says Fumiaki Obata of the RIKEN Center for Biosystems and Dynamics Research (BDR).

Known as tyrosine, the amino acid is found in dairy products, meats, nuts, beans and other protein-packed foods. But the body can also synthesize tyrosine from another amino acid called phenylalanine, which is similarly found in both plant and animal foods.

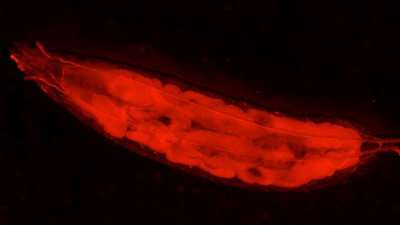

As Obata and BDR colleague Hina Kosakamoto have now shown, the flies slow down their rate of protein metabolism and ramp up food consumption when levels of tyrosine in the diet are low—a sign of adaptation to protein scarcity. But, conversely, when tyrosine is ingested in greater amounts, the flies kick their protein metabolism into high gear. They also limit intake of extra protein, thus ensuring that levels of the macronutrient remain within a healthy range.

The team identified several of the molecular players and signaling pathways involved in regulating the body's response to tyrosine levels—although how exactly this happens remains unclear. They ruled out one common mechanism by which the brain senses nutrient imbalances. But as Kosakamoto points out, "We still don't know how tyrosine is sensed in cells."

Another research priority for the team is to corroborate the findings in mouse models. This will help determine how relevant the results are for human physiology and medicine, as well as for agriculture and animal husbandry. "If tyrosine plays a similar role in mammals, then we could use tyrosine restriction to control appetite, treat metabolic syndrome or even forestall aging," Obata says. "Potentially, our knowledge could also be applied in the livestock industry to improve animal health and production."

The study is published in Nature Metabolism.

More information: Hina Kosakamoto et al, Sensing of the non-essential amino acid tyrosine governs the response to protein restriction in Drosophila, Nature Metabolism (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s42255-022-00608-7

Journal information: Nature Metabolism

Provided by RIKEN