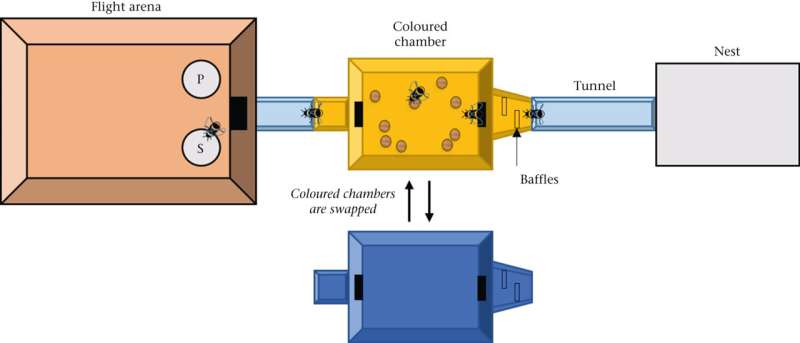

Experimental set-up for the training stage (aerial view). A nest was connected to a colored chamber via a tunnel. The chamber was connected to a flight arena with feeders providing ad libitum sucrose (S) or pollen (P); their positions were swapped each experimental day. The colored training chamber was either yellow or blue. One of the colored chambers contained movable balls and the other was empty. Baffles at the entrance of the colored chamber prevented bees seeing the presence/absence of objects. Only one colored chamber was presented at a time and they were alternated every 20 min (six times each) for a total of 2 h exposure for each color. One group of bees was trained with the yellow chamber containing balls and the other group with the blue chamber containing balls. This experimental stage was carried out on 2 consecutive days for each bee. Credit: Animal Behaviour (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2022.08.013

Bumble bees play, according to new research led by Queen Mary University of London published in Animal Behaviour. It is the first time that object play behavior has been shown in an insect, adding to mounting evidence that bees may experience positive "feelings."

The team of researchers set up numerous experiments to test their hypothesis, which showed that bumble bees went out of their way to roll wooden balls repeatedly despite there being no apparent incentive for doing so.

The study also found that younger bees rolled more balls than older bees, mirroring human behavior of young children and other juvenile mammals and birds being the most playful, and that male bees rolled them for longer than their female counterparts.

A bee rolling a balls. Credit: Samadi Galpayage.

The study followed 45 bumble bees in an arena and gave them the options of walking through an unobstructed path to reach a feeding area or deviating from this path into the areas with wooden balls. Individual bees rolled balls between 1 and, impressively, 117 times over the experiment. The repeated behavior suggested that ball-rolling was rewarding.

This was supported by a further experiment where another 42 bees were given access to two colored chambers, one always containing movable balls and one without any objects. When tested and given a choice between the two chambers, neither containing balls, bees showed a preference for the color of the chamber previously associated with the wooden balls.

The set-up of the experiments removed any notion that the bees were moving the balls for any greater purpose other than play. Rolling balls did not contribute to survival strategies, such as gaining food, clearing clutter, or mating and was done under stress-free conditions.

An example of ball rolling by a bumble bee at speed ×0.5. The bee approaches a wooden colored ball while facing it, touches the ball with her forelegs, holds onto the ball using all of her legs, rolls the ball, detaches from and leaves the ball. The bee approaches a second ball, rolls it and detaches. Credit: Animal Behaviour (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2022.08.013

The research builds on previous experiments from the same lab at Queen Mary, which showed that bumble bees can be taught to score a goal, by rolling a ball to a target, in exchange for a sugary food reward. During the previous experiment, the team observed that bumble bees rolled balls outside of the experiment, without getting any food reward.

The new research showed the bees rolling balls repeatedly without being trained and without receiving any food for doing so—it was voluntary and spontaneous—therefore akin to play behavior as seen in other animals.

Study first-author, Samadi Galpayage, Ph.D. student at Queen Mary University of London says that "it is certainly mind-blowing, at times amusing, to watch bumble bees show something like play. They approach and manipulate these 'toys' again and again. It goes to show, once more, that despite their little size and tiny brains, they are more than small robotic beings."

"They may actually experience some kind of positive emotional states, even if rudimentary, like other larger fluffy, or not so fluffy, animals do. This sort of finding has implications to our understanding of sentience and welfare of insects and will, hopefully, encourage us to respect and protect life on Earth ever more."

Professor Lars Chittka, Professor of Sensory and Behavioral Ecology at Queen Mary University of London, head of the lab and author of the recent book The Mind of a Bee, says that "this research provides a strong indication that insect minds are far more sophisticated than we might imagine. There are lots of animals who play just for the purposes of enjoyment, but most examples come from young mammals and birds."

"We are producing ever-increasing amounts of evidence backing up the need to do all we can to protect insects that are a million miles from the mindless, unfeeling creatures they are traditionally believed to be."

More information: Hiruni Samadi Galpayage Dona et al, Do bumble bees play?, Animal Behaviour (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2022.08.013

Journal information: Animal Behaviour

Provided by Queen Mary, University of London