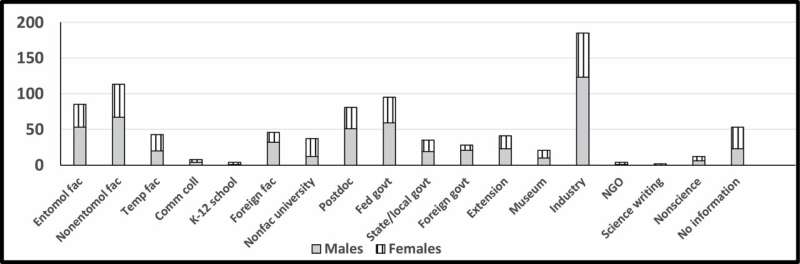

Gender distribution of 2001–2018 entomology doctoral graduates among occupational categories in 2021. Credit: Annals of the Entomological Society of America (2022). DOI: 10.1093/aesa/saac018

Women pursuing careers in entomology face persistent challenges in obtaining jobs compared to men, according to a new study analyzing career tracks of recent entomology doctoral graduates.

Among entomologists obtaining Ph.D.s between 2001 and 2018, significantly more men than women held industry positions as technical representatives and research scientists as of 2021. Across job categories, women outpaced men only in nonfaculty university positions. Meanwhile, men published significantly more research articles than women during their graduate programs and then went on to attain higher measures of publishing volume and influence.

Entomologist Karen Walker, Ph.D., retired from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, conducted the analysis, published October 12 in the Annals of the Entomological Society of America. She says these findings should be cause for concern for university entomology programs that seek to be drivers of opportunity for a diverse crop of aspiring professionals in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields.

"Why should a woman enroll in an entomology program if she knows or finds out that she will be less successful in getting a job than if she enrolls in another STEM program?" Walker says. "What's going to happen to university entomology programs if enrollment drops?"

The new study builds on Walker's previous research into the gender gap in entomology. In 2018, she reported that men exceed women in university and federal entomology jobs by a roughly 3-to-1 ratio, even though women had earned more than 40 percent of doctoral degrees in entomology for the preceding decade.

Her latest analysis illuminates the apparent hurdles in career advancement that women face in entomology. For example, 18 percent of men in the study found jobs in the year they graduated, while 12 percent of women did. Meanwhile, at five years after graduation, significantly more men than women had obtained jobs as entomology professors or in the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And by 2021, while 17 men in the study had earned full-professor status in university entomology departments, just one woman had.

A variety of underlying factors, some unique to entomology and others common across STEM fields, may be at play, Walker says. Her research uncovered one clear dynamic that gives men in entomology a head start: As graduate students, men in the study published more of their research in academic journals than women did.

Men published an average of 3.5 research articles during their time as graduate students, while women averaged 2.5 published articles. Similarly, men were first authors on 2.3 articles on average, while women were first authors on an average of 1.4 articles.

This advantage led to higher average scores for men than women as measured by their H index, which compares an author's volume of published articles and level of citations those articles have received. (For example, an author with an H index of 5 has published at least five research articles that have each received five citations in other publications.)

Among graduates in the study hired to university faculty roles, men's H indices in 2021 exceeded women's whether working in entomology departments (19.5 average H index for men versus 15.2 for women) or non-entomology departments (16.6 versus 11.8).

As in many fields, graduate studies and early professional years often coincide with starting families, which can disproportionately affect women's career tracks. Walker's findings illustrate how this may be playing out within entomology.

"I think that students and early-career women in entomology should try to obtain relationships with as many potential collaborators as possible and to publish as often as possible," Walker says.

"If taking a break for parental leave or family leave, I'd encourage women to maintain as many ties with other scientists as possible and to continue doing research as possible. This might be very difficult, unfortunately. But the alternative often appears to be that the woman is viewed by potential employers as though she doesn't have the qualifications for jobs simply because she took a break to focus on her family."

Over the past 15 years, the Entomological Society of America (ESA) has seen significant increases in women members, primarily in student, student-transition, and early-career membership levels. But retention among women has been less than among men. Notably, however, women entomologists have risen to top leadership ranks in the organization in recent years; ESA members have elected a woman entomologist to serve as ESA president in four of the past seven years as well as each of the next three years.

Among efforts to enhance gender equity within entomology, ESA has instituted a stringent ethics statement with a code of conduct and reporting process aimed at eliminating harassment at its events, supported a "Women in Entomology" breakfast at its annual conference, increased its funding to support childcare for conference attendees, and provided private spaces for nursing mothers at its events.

In 2022, the Society also launched a salary benchmarking program that will enable analysis of compensation practices across various job types and employee demographics.

"Dr. Walker's research shows we have plenty of work to do in building an equitable field of entomology," says ESA President Jessica Ware, Ph.D. "The findings in this study are one clear example of why equity work is so important. At ESA we want entomologists of all backgrounds to succeed and grow our science, and we celebrate the diversity of gender identity, race, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation found among our members."

More information: Karen A Walker et al, Longitudinal Career Survey of Entomology Doctoral Graduates Suggests That Females Are Disadvantaged in Entomology Job Market, Annals of the Entomological Society of America (2022). DOI: 10.1093/aesa/saac018

Provided by Entomological Society of America