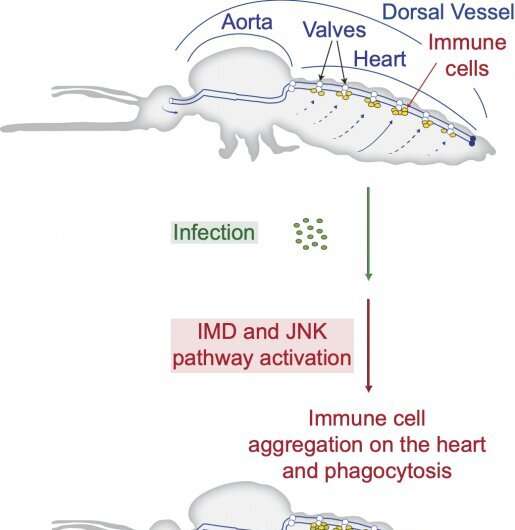

Diagram showing the components of the circulatory systems of mosquitoes, and the infection-induced recruitment of immune cells to the heart by the IMD and JNK pathways. Credit: Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt biologists have discovered the genetic pathways that link the immune and circulatory systems of mosquitoes during the fight against infection. A mosquito fighting infection of malaria or bacteria attracts immune cells to its heart that filter microbes that are flowing in its blood, called hemolymph. The discovery of two pathways that link immunity and hemolymph circulation is a major contribution to the understanding of how mosquitoes, which are themselves disease vectors, respond to infection.

Julián F. Hillyer, professor of biological sciences, and his research team investigate the physiology of mosquitoes and, specifically, how the mosquito heart pumps hemolymph, how its immune cells fight infection and how these processes interact.

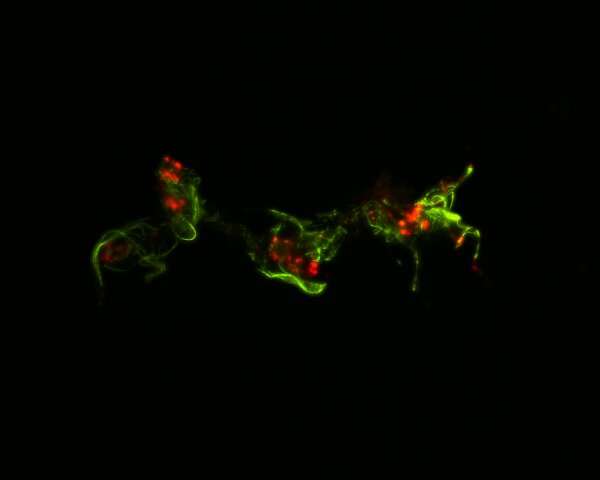

In some cases, mosquitoes beat infection through immunologically active cells in the heart. Because the circulatory system of mosquitoes contains only one contracting vessel and no arteries or veins, their hemolymph flows freely throughout the body. "Insects deploy a powerful immune response against infection, with immune cells aggregating on the heart to destroy passing microbes. Yet, the genetic mechanisms that guide these immune cells to the heart remained unknown," said Yan Yan, Ph.D., a lead researcher on the project.

Hillyer's team studied the expression of every gene in the mosquito heart and identified the genetic pathways that become significantly activated on the heart when an infection occurs. By disrupting these pathways using a technique called RNA interference, the researchers discovered how the genetic pathways are involved.

Mosquito heart, removed from the abdomen of a mosquito. Heart muscle is shown in green, and immune cells are shown in red. Credit: Vanderbilt University

The immune deficiency pathway, which produces and secretes immune proteins, also recruits free-floating immune cells to settle on the heart. The team also found that a pathway that plays a role in longevity, reproduction and defense brings immune cells to the heart. Immune cells that arrive on the heart eat and digest microbes, increasing a mosquito's likelihood to overcome infection.

Hillyer, Yan and their team hypothesize that the genetic pathways identified in this study drive immune responses on the hearts of other insects—including disease vectors, agricultural pests and crop pollinators—because the immune and circulatory systems are functionally integrated throughout the insect tree of life and are evolutionarily conserved in the insect lineage.

"This research could lay the foundation for novel strategies that protect beneficial insects or harm detrimental ones," Hillyer added.

To continue this advance in knowledge, Hillyer's team is investigating how pathway disruption affects insect heart contractions and is looking for heart-specific factors that act as "homing signals" for the arrival of immune cells on the heart.

The article, "The immune deficiency and c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathways drive the functional integration of the immune and circulatory systems of mosquitoes" was published in the journal Open Biology on Sept. 7.

More information: Yan Yan et al, The immune deficiency and c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathways drive the functional integration of the immune and circulatory systems of mosquitoes, Open Biology (2022). DOI: 10.1098/rsob.220111

Journal information: Open Biology

Provided by Vanderbilt University