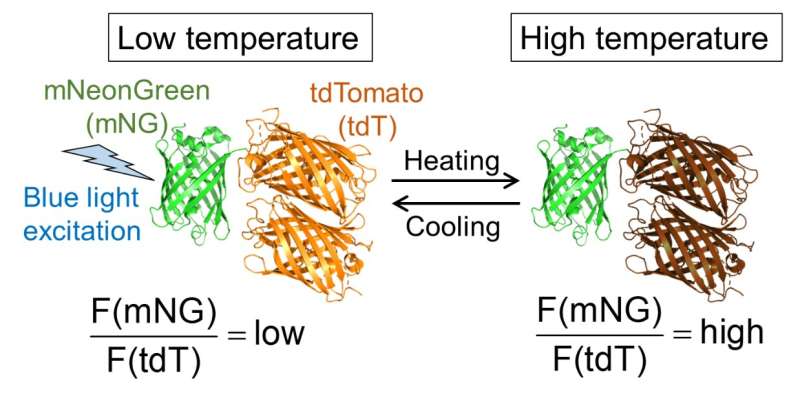

Fig.1. Molecular design of B-gTEMP and the expected fluorescence response to temperature. F(mNG) and F(tdT) are fluorescence intensity of mNeonGreen and tdTomato, respectively. Credit: Kai Lu et al.

Body temperature is a basic indicator of health. Intracellular temperature is also a basic indicator of cellular health; cancer cells are more metabolically active, and thus can have a slightly higher temperature than healthy cells. However, until now the available tools for testing such hypotheses haven't been up to the task. In a study recently published in Nano Letters, researchers from Osaka University and collaborating partners have experimentally measured temperature gradients within human cells and at unprecedented precision. This study will open up new directions in drug discovery and medical research.

Many researchers have suspected that transient intracellular temperature gradients have a broader effect on human health than commonly appreciated but were unable to test their hypotheses owing to the limitations of the technology available to them. "Current intracellular thermal detection technology has insufficient spatial, temporal, and readout resolution to answer some long-standing medical hypotheses," explains Kai Lu, lead author, "but our research changes this. Our genetically encoded fluorescent nanothermometer overcomes prior technical hurdles and will be invaluable for testing such hypotheses."

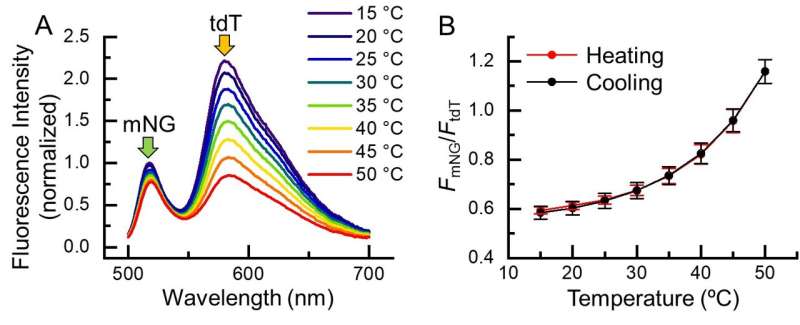

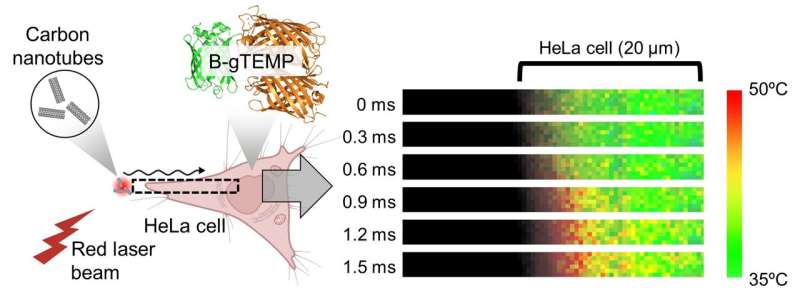

The researchers' protein-based nanothermometer is based on modulated fluorescence output that's sensitive to small changes in temperature within cells. Its readout speed is at least 39 times faster than comparable technology, and a thousand times faster than a typical blink of your eye. The nanothermometer enabled the researchers to discover that intracellular heat diffusion is more than 5 times slower than heat diffusion in water. It also showed that the readout resolution is only 0.042 degrees Celsius at physiological temperature, which is an even higher resolution than that in a comparable setup that's several thousand times slower.

Fig. 2. Temperature response of B-gTEMP. (A) Fluorescence spectrum of B-gTEMP at various temperatures. mNG: mNeonGreen; tdT: tdTomato. (B) Fluorescence intensity ratio of mNG to tdT in response to temperature during a cycle of heating and cooling. Credit: Kai Lu et al.

"We tested the hypothesis that there's a substantial temperature difference between the cell nucleus and cytoplasm," says Takeharu Nagai, senior author. "We didn't find a significant difference, but test conditions that more closely mimic typical physiology might give different results."

Fig. 3. Rapid heat transport in cells. Heat was generated by irradiating carbon nanotubes with a focused red laser beam; the heat then diffused into the adjacent HeLa cell. This process was captured in real time by kilohertz temperature imaging with B-gTEMP. Credit: Kai Lu et al.

There are several means of improving the functionality of the researchers' nanothermometer. One is to improve how long it lasts under microscopic illumination. Another is to reengineer it to be sensitive to red or infrared light, and thus be less damaging to cells for long-term imaging. In the meantime, researchers now have the technology to realistically probe intracellular temperature gradients, and uncover the physiology that underpins these gradients. Perhaps with this knowledge, drugs can one day be designed to take advantage of this underappreciated aspect of cell physiology.

More information: Kai Lu et al, Intracellular Heat Transfer and Thermal Property Revealed by Kilohertz Temperature Imaging with a Genetically Encoded Nanothermometer, Nano Letters (2022). DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c00608

Journal information: Nano Letters

Provided by Osaka University