Precursor of spine and brain forms passively

Researchers at ETH Zurich have conducted a detailed study of neurulation—how the neural tube forms during embryonic development. They conclude that this happens less actively than previously thought. This also has implications for understanding defects such as spina bifida.

In the human embryo, the neural tube forms between the 22nd and 26th day of pregnancy. Later, the brain and spinal cord will develop from this tube. The neural tube forms when an elongated flat tissue structure, the neural plate, bends lengthwise into a U shape and closes to form a tube. What drives this development is not yet clear. Researchers in the group of Dagmar Iber, Professor of Computational Biology at the Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering at ETH Zurich in Basel, have now been able to show that the surrounding tissue is likely to play a significant role by exerting pressure from the outside.

The formation of the neural tube is an extremely important step in embryonic development, as ETH Professor Iber points out. In about one in a thousand embryos, this tube does not form completely. These children are born with a spinal malformation called spina bifida (from the Latin for "split spine"); in extreme cases, they are born with an "open back" (spina bifida aperta) that requires surgery. Not least in order to better prevent this kind of birth defect, scientists would like to understand neurulation—the process of forming the neural tube—in as much detail as possible.

"In recent decades, this question has been the focus of intense research," says Roman Vetter, a scientist in Iber's group and co-author of the new study, which the researchers are now publishing in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It is known that linear regions in the middle and on the sides of the neural plate are particularly strongly curved. These regions are called hinge points. Until now, scientists assumed that local biochemical signals in the cells of the neural plate lead to the formation of these hinge points, and that the hinge points play an active role in the formation of the neural tube. However, there has been no explanation as to why the hinge points form exactly where they do.

Computer modeling leads the way

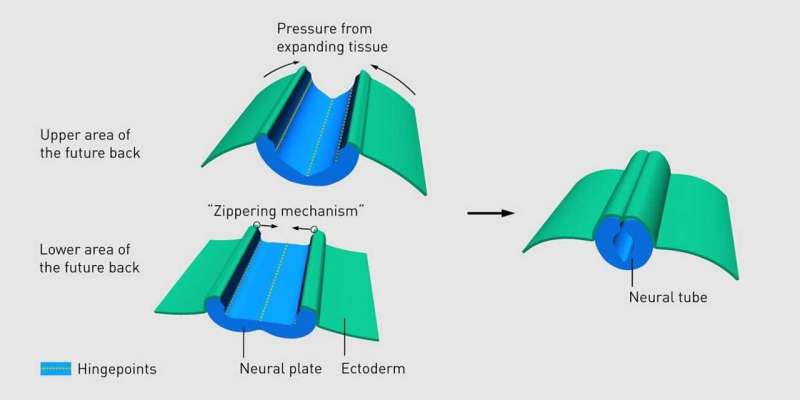

The ETH researchers now postulate an alternative mechanism, according to which the neural plate does not actively bend itself, driven by the hinge points, to form a tube. Rather, the neural plate initially adopts a slightly curved shape for anatomical reasons. Subsequently, the tissue lying either side of the neural plate (ectoderm and mesoderm) expands. This applies pressure to the neural plate from the side and causes it to passively form into a tube.

The researchers arrived at these findings with the help of computational modeling. Using existing image data from human and mouse embryos, the researchers created a computer model of neurulation based on the physical laws of nature. They then used a supercomputer at ETH Zurich to simulate several possible mechanisms for forming the neural tube.

This showed that the processes were best explained by the expansion of the surrounding tissue. "We use this to demonstrate that hinge points can arise as a result of external pressure. So they are probably not drivers of neurulation, as was previously thought, but a side effect of it," Iber says. Instead, the driver appears to be the surrounding tissue.

Further mechanism in the lower back

Especially in the upper part of the back, neurulation can be explained by the expansion of the adjacent tissue, because for anatomical reasons the neural plate is slightly pre-bent already. Further down the future back, this initial curvature is absent; the neural plate is flat in this area.

With their modeling, the ETH scientists were able to show that here, too, neurulation can be explained by external forces: protein fibers and anchor proteins help to pull the neural plate together like a zip. This causes the neural plate to curve and close into a tube.

According to the researchers, the fact that the mechanisms differ in the upper and lower back could explain why spinal malformations don't occur with the same frequency all along the back. Spina bifida is more common in the lower back, where the surrounding tissues are less supportive.

"We were able to show that mechanical effects are responsible for neurulation," Vetter says, "and our computer modeling was the key to revealing this in the first place." ETH Professor Iber adds, "It's impossible to demonstrate and understand a mechanical effect using biological and genetic experiments alone, without such simulations." Experimental researchers are now likely to try to confirm the ETH researchers' predictions with experiments in animals.

The aim is also to get one step closer to the causes of defects and thus their prevention. It is known that a deficiency of folic acid as well as other deficiency symptoms promote these malformations of the spine. Further research is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms in detail.

More information: Veerle de Goederen et al, Hinge point emergence in mammalian spinal neurulation, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2117075119

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by ETH Zurich