Why haven't we discovered co-orbital exoplanets? Tides may offer a possible answer

In our solar system, there are several thousand examples of co-orbital objects: bodies that share the same orbit around the sun or a planet. The Trojan asteroids are such an example. We have not yet observed any similar co-orbitals in extrasolar systems, despite discovering more than 5,000 exoplanets. In a new study published in Icarus by Anthony Dobrovolskis, SETI Institute, and Jack Lissauer, NASA Ames Research Center, the authors theorize that some Trojan exoplanets form, but the ones that are large and on short-period orbits (and thus relatively easy to detect) are typically forced out of shared orbit by tides. They collide with either their star or their giant planet when that happens.

'"If or when Trojan exoplanets are discovered, this work may help to reveal some properties of their internal structures," said Dobrovolskis, research scientist at the SETI Institute.

Here on Earth, friction caused by tides causes Earth's rotation to slow down, resulting in our moon moving away from Earth. Generalizing the theory of tidal friction to systems with more than two bodies, the authors apply the theory to systems that include a star, a giant planet, and an Earth-like planet oscillating around a giant planet's L4 or L5 or the giant planet's equilateral point.

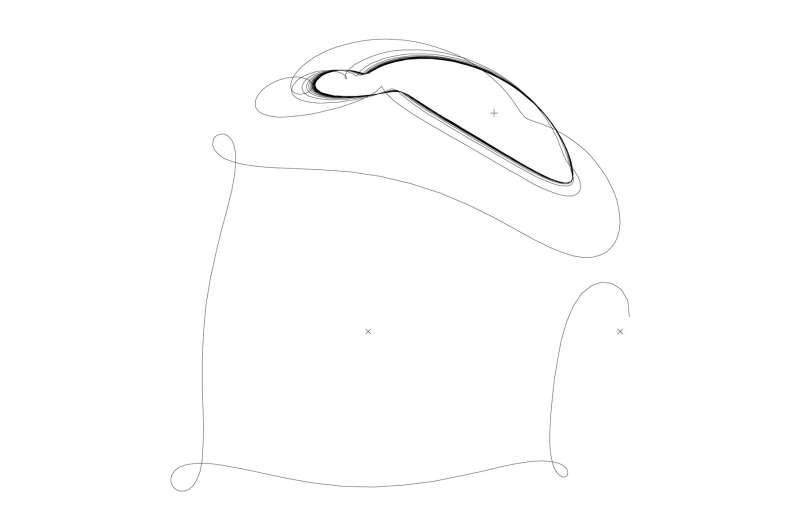

Based on their analysis, the tides raised by the star and the giant planet on the Earth-like planet caused its oscillations to grow until they became unstable. The researchers did numerical simulations that show the Trojan's oscillations change from oval-shaped to banana-shaped and ultimately break out of the shared orbit, colliding with either the star or the giant planet.

The findings are consistent with previously published results from 2013 by Rodriguez et al., and in 2021 by Couturier et al. This suggests that tides are removing co-orbital exoplanets before we can observe them. If that's the case, we may yet discover co-orbital exoplanets. It's also possible that NASA's Lucy mission to the Trojan asteroids, which launched last October, may provide additional clues about the role of tides in co-orbital systems.

More information: Anthony R. Dobrovolskis et al, Do tides destabilize Trojan exoplanets?, Icarus (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2022.115087

Journal information: Icarus

Provided by SETI Institute