Credit: fauxels from Pexels

There are many reasons to employ people living with intellectual disability. Most obvious is that it's the right thing to do—it helps promote social justice, diversity, corporate social responsibility, and equal opportunity.

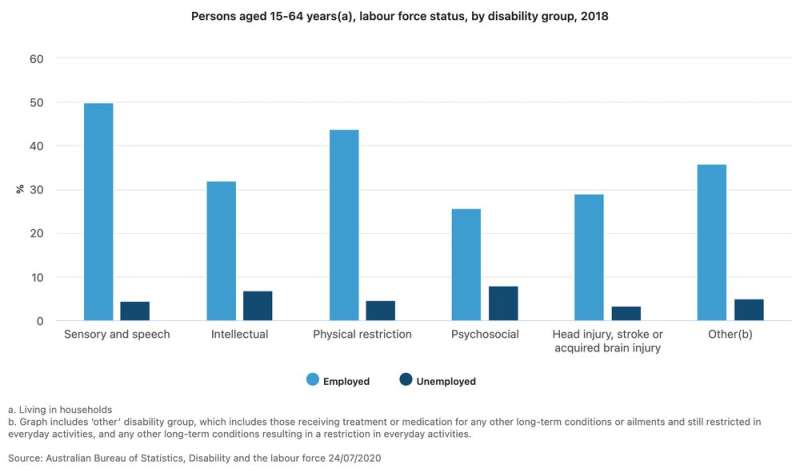

Even so, data released in 2020 (the latest available) show just 53.4% of people with disability are in the labor force, compared with 84.1% of people without disability.

The situation is worse for people living with intellectual disability; only 32% of this group are employed.

People living with intellectual disability are ready, willing and able to work.

What employers often don't realize is that hiring from this oft-neglected segment of the workforce can also bring benefits for business.

Resilience, perseverance and positive outlook

The recent Australian television documentary series, Employable Me, highlighted the employment difficulties faced by people living with a disability.

It's hard not to admire the incredible resilience, perseverance and positive outlook of this group.

Despite these qualities, people living with intellectual disability who want to work face barriers such as:

- employer attitudes

- stigma

- preconceived beliefs

- discriminatory work practices and

- a limited knowledge of their capabilities.

It's true employers may need to make workplace adjustments to accommodate these employees' needs, such as:

- communicating in pictures rather than words (for example, using signage with symbols to indicate who and what goes where)

- breaking tasks down into simple steps

- specialized training for workers living with an intellectual disability, as well as supervisors and co-workers.

Yes, these changes may represent an initial cost. But research shows the profound benefits of hiring people living with intellectual disabilities, which can include:

- improvements in profitability

- greater cost-effectiveness

- lower employee turnover

- high rates of employee retention, reliability, punctuality, loyalty, and

- benefits to the company image.

Persons aged years a labour force status by disability group. Credit: Australian Bureau of Statistics

The organizations highlighted in such studies include retail organizations, the military, small and medium enterprises, professional services and landscaping.

To achieve such results though, requires employee support, changes to work procedures, flexibility in supervision, and—perhaps most importantly—an open mind.

'A massive waste of human resource'

People living with intellectual disability can and do make a significant contributions at work when given the opportunity.

Many tend to be employed part-time, and in segregated settings—often in Australian disability enterprises or what used to be called "sheltered workshops."

One of us (Elaine Nash) has been researching the business benefits of employing people living with intellectual disability. The (yet to be published) research has involved interviews with policy makers, leaders, disability advocates, managers, employers, and staff.

One interview was with Professor Richard Bruggemann, a disability advocate and last year's South Australia Senior Australian of the year. He described the low labor force participation rate of people living with an intellectual disability as "a massive waste of human resource."

He said: "People living with intellectual disability are ready, willing, and able to make a difference to organizations beyond the traditional sheltered workshop setting. All they need is an opportunity to do so."

Bruggemann's observations are supported by international research about workers living with intellectual disability. Many studies have called for a whole-of-government approach to boost employment rates in this cohort.

Making it happen

Employing people living with intellectual disability won't always be suitable.

It is not a silver bullet for corporate success, higher efficiency, or greater profits. But in some settings, it may help address problems that have been concerning employers.

As Simon Rowberry, CEO of Barkuma (a not-for-profit that supports people with disability) told us in an interview: "There are costs and benefits in any employment decision. Incorporating workers living with intellectual disability into your workforce is no different. Preparation, understanding what the upsides as well as the downsides are, and a need to be flexible are non-negotiables."

Perhaps the most critical success factor is a genuine desire to make it happen. Where there's a will, there's usually a way.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()