Stressed out worms use epigenetic inheritance to produce more sexually attractive offspring

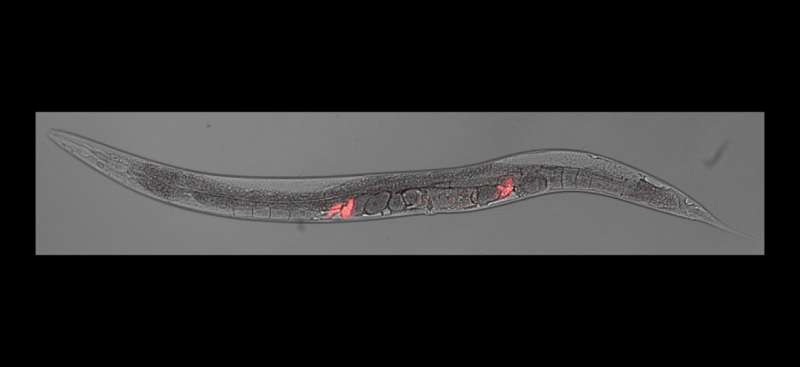

Sexual reproduction allows organisms to mix up their genes and develop new adaptations to survive a harsh and ever-changing environment. Under nutrient-rich conditions, the worm C. elegans is typically asexual, but after enduring several generations of stress, the worms begin to reproduce sexually and release pheromones to appear more sexually attractive to male worms. In the journal Developmental Cell on February 7th, researchers have determined how sexual attractiveness is passed on, and that it occurs not through modification of the worm's DNA, but instead through the transfer of small RNAs.

"For over a decade we've been studying a very controversial question: can parental responses to environmental challenges transmit from generation to generation?" says Oded Rechavi, lead author of the study and a professor studying RNA memory inheritance at Tel Aviv University. "We know that this can't happen via changes to the DNA sequence, but surprisingly our work and the work of many others show that it can happen, at least in simple organisms (notably C. elegans nematodes), via inheritance of small RNA molecules."

Small RNAs can influence an organism's gene expression through a phenomenon known as gene silencing. "Unlike the DNA, small RNAs are synthesized in response to certain environmental conditions, leading to gene expression changes that persist across generations to progeny that weren't exposed to the stressful environment," says co-author Yael Mor and MD-Ph.D. student at the Rechavi lab.

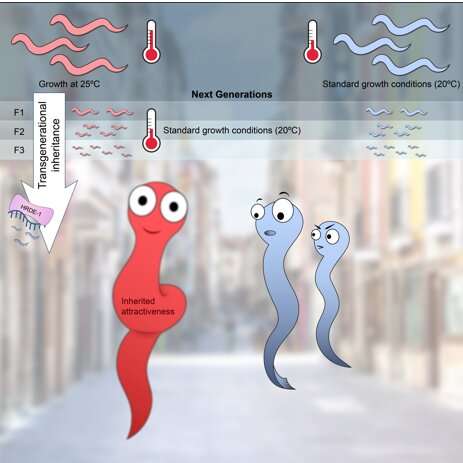

The researchers simulated mildly stressful conditions in the lab by raising the worms at 25°C, which is warm for the worms, but within the standard temperature range for lab cultures. Normally, the hermaphroditic worms would wait until the end of their life cycle when they stop producing sperm to start secreting male-attracting pheromones, but these stressful conditions triggered the worms to become prematurely attractive to males.

"An additional exciting aspect of our study is that sperm and sperm small RNAs can serve as a stress sensor (or a rheostat)," says Rechavi. His team found that elevated temperatures induced defects in the worm's sperm, and this is what triggers the increase in sexual attraction under environmental stress.

To identify the pathway by which the worms regulate sexual attraction, the researchers examined worms with different small RNA species turned off and tested if they were more attractive than normal worms. "We developed a unique system that allows us to eliminate the Argonaute protein HRDE-1 that binds heritable small RNAs," says co-author Itamar Lev, former Ph.D. student in the Rechavi lab and now a postdoc at the University of Vienna. "We found that removing HRDE-1 in the descendants (depleting the heritable small RNAs) eliminates the inheritance of the attractiveness."

"One result that surprised us at first was that the hermaphrodites won't secrete the male-attracting pheromone right away when grown at higher temperatures: they wait about ~10 generations (~4 weeks) before raising their attractiveness," says co-author Itai Toker, former Ph.D. student in the Rechavi lab and now postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University. "In retrospect, this makes a lot of sense—persisting experience from previous generations can provide a relatively robust 'prediction' to organisms that this environment might persist for longer."

C. elegans has a unique dual-mode reproductive strategy, but Rechavi's team hopes to determine if similar heritable effects occur in other organisms. "This work connects short term epigenetic inheritance with long term, hard-wired genetic changes, and thus with the process of evolution," says Yael Mor.

More information: Oded Rechavi, Transgenerational Inheritance of Sexual Attractiveness via Small RNAs Enhances Evolvability in C. elegans, Developmental Cell (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2022.01.005. www.cell.com/developmental-cel … 1534-5807(22)00005-3

Journal information: Developmental Cell

Provided by Cell Press