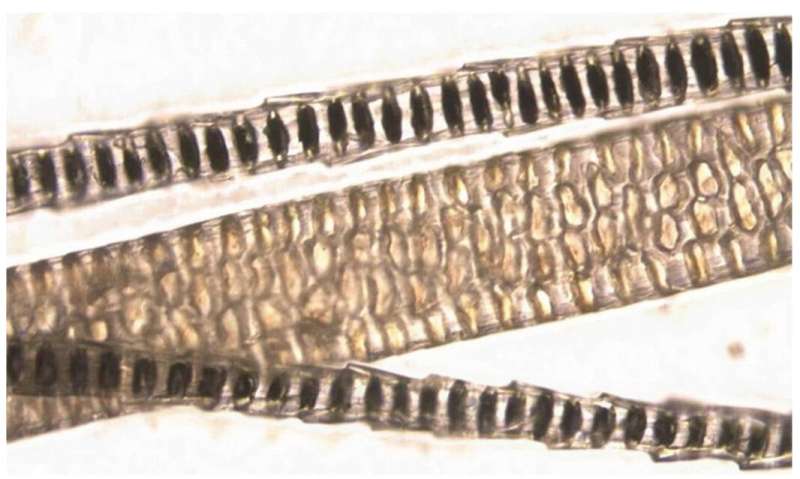

Figure 1. Two hair types from Mus musculus showing characteristic banding and a scale compatible with an infrared function. The small hairs are so-called zigzag hairs and the large one is the widest part of a spear-shaped guard hair—approximately the same width as a human hair. Credit: DOI: 10.1098/rsos.210740

Ian Baker, a physicist specializing in camera imaging, who works for Leonardo U.K. Ltd., a British defense company, has discovered that a bristly type of mouse hair has structures that resemble those in some manmade optical sensors. In his paper published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, Baker suggests that mouse and other mammalian fur may serve as infrared antennas—allowing its owner to sense heat.

Mice serve as prey for a wide variety of predators, including snakes, owls and cats, and have therefore evolved a number of senses to help them survive. They have sharp eyesight, for example, and a keen sense of smell, and acute hearing. In this new effort, Baker suggests that they may have another sense, as well—the ability to sense heat emanating from the bodies of predators.

Baker made this discovery while using specialized cameras to study wildlife around his home in Southampton, England. As part of that work, he noticed that predators sneaking up on mice quite often behaved in ways that suggested they were trying to shield their heat emanations. Cats, for example, slunk down to keep their bodies behind their heads which were fronted by cold noses. And owls twisted awkwardly as they dived after prey, seemingly to keep their warm parts hidden from view.

Intrigued, Baker captured some of the mice and cut off some of their fur, which he placed under a microscope. He found that the structure of the guard hair looked a lot like the structures he was used to seeing in his optical equipment at work. After taking measurements, he found that the span between the fur structural parts was approximately 10 microns, which, he notes, is the same spacing used in manmade optical sensors—it corresponds to 10-micron radiation.

Baker then obtained fur samples from several other small animals that often serve as prey—squirrels, antechinus and shrews—and found they all had similar structures with the same 10-micron features. He suggests that the fur presents a strong case for heat sensing in such animals. He suggests that biologists in the field take a closer look to find out if there are any sensors in the skin of such animals that could process heat sensing data from the fur.

More information: Ian M. Baker, Infrared antenna-like structures in mammalian fur, Royal Society Open Science (2021). DOI: 10.1098/rsos.210740

Journal information: Royal Society Open Science

© 2021 Science X Network