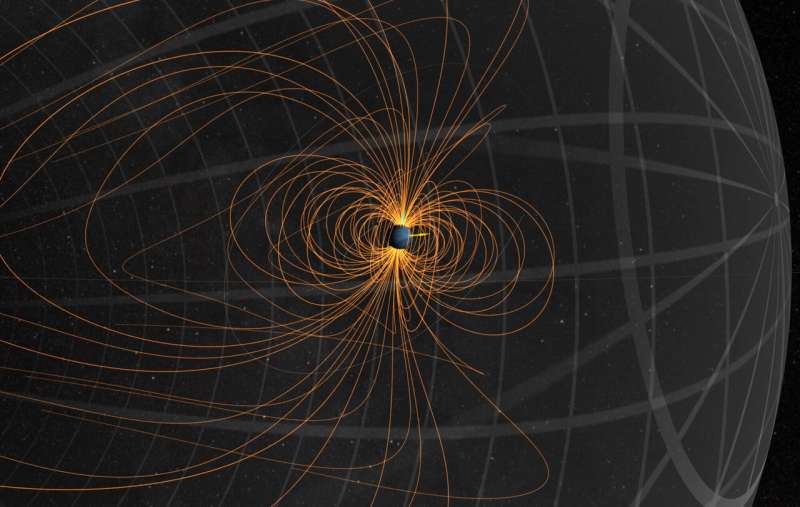

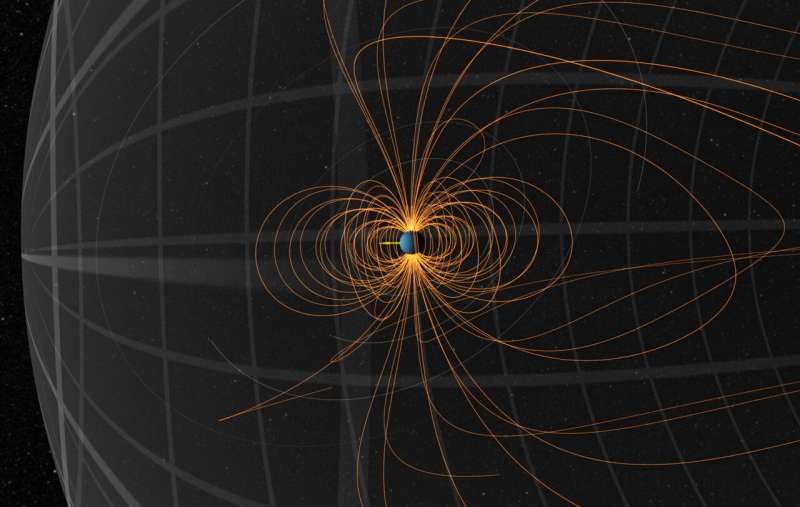

The magnetic field of Neptune, like that of the Earth, is not static but varies over time. Pictured is a snapshot from August 2004. Credit: NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio

Not all ice is the same. The solid form of water comes in more than a dozen different—sometimes more, sometimes less crystalline—structures, depending on the conditions of pressure and temperature in the environment. Superionic ice is a special crystalline form—half solid, half liquid—and electrically conductive. Its existence has been predicted on the basis of various models and has already been observed on several occasions under extreme laboratory conditions. However, the exact conditions at which superionic ices are stable remain controversial.

A team of scientists led by Vitali Prakapenka from the University of Chicago, which also includes Sergey Lobanov from the German Research Center for Geosciences GFZ Potsdam, has now measured the structure and properties of two superionic ice phases (ice XVIII and ice XX). They brought water to extremely high pressures and temperatures in a laser-heated diamond anvil cell. At the same time, the samples were examined with regard to structure and electrical conductivity. The results were published today in the renowned journal Nature Physics. They provide another piece of the puzzle in the spectrum of the manifestations of water. And they may also help to explain the unusual magnetic fields of the planets Uranus and Neptune, which contain a lot of water.

Hot ice?

Ice is cold; at least type I ice from our freezer, snow or from a frozen lake. In planets or in laboratory high-pressure devices, there are different species of ice, type VII or VIII for example, which exist at several hundred or thousand degrees Celsius. However, this is only because of very high pressures of several tens of Gigapascal.

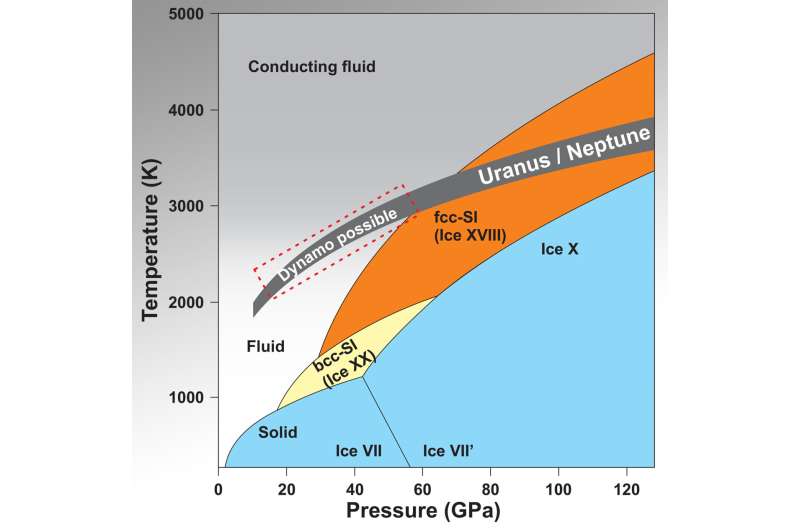

Pressure and temperature span the space for the so-called phase diagram of a substance: Depending on these two parameters, the various manifestations of water and the transitions between solid, gaseous, liquid and hybrid states are recorded here—as they are predicted theoretically or have already been proven in experiments.

Shown is a snapshot of the magnetic field of Uranus in January 2007. Credit: NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio

Linking fundamental physics with geological questions

The higher the pressure and temperature, the more difficult such experiments are. And so the phase diagram of water—with ice as its solid phase—still has quite a few inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the extreme ranges.

"Water is actually a relatively simple chemical compound consisting of one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms. Nevertheless, with its often unusual behavior, it is still not fully understood. In the case of water, the fundamental physical and geoscientific interests come together because water plays an important role inside many planets. Not only in terms of the formation of life and landscapes, but—in the case of the gaseous planets Uranus and Neptune—also for the formation of their unusual planetary magnetic fields," says Sergey Lobanov, geophysicist at GFZ Potsdam.

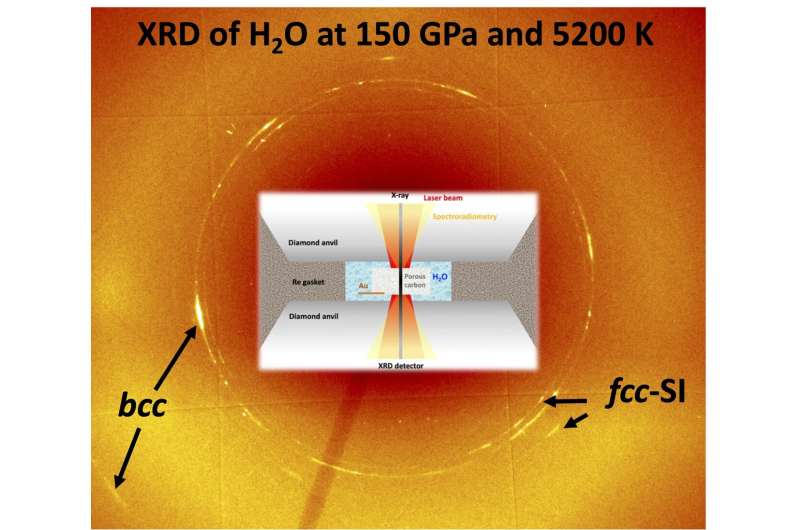

Figure illustrating how the experiments were performed, revealing two forms of superionic ice. Credit: Vitali Prakapenka

Unique conditions in the lab

Sergey Lobanov is part of the team led by first author Vitali Prakapenka and Nicholas Holtgrewe, both from the University of Chicago, and Alexander Goncharov from the Carnegie Institution of Washington. They have now further characterized the phase diagram of water at its extremes. Using laser-heated diamond anvil cells—the size of a computer mouse—they have generated high pressures of up to 150 Gigapascal (about 1.5 million times atmospheric pressure) and temperatures of up to 6,500 Kelvin (about 6,227 degrees Celsius). In the sample chamber, which is only a few cubic millimeters in size, conditions then prevail that occur at the depth of several thousand kilometers inside Uranus or Neptune.

The scientists used X-ray diffraction to observe how the crystal structure changes under these conditions. They carried out these experiments using the extremely bright synchrotron X-rays at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) of the Argonne National Laboratory at the University of Chicago. A second series of experiments at the Earth and Planets Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution of Washington used optical spectroscopy to determine the electronic conductivity.

The phase diagram shows the state of water (H2O) under very high pressure (X-axis) and temperature conditions (Y-axis). These conditions apply in the interior of the ice planets Uranus and Neptune (dark grey field), where states are reached in which the water becomes electrically conductive and is thus able to generate magnetic fields (red dotted area). For comparison: At the core-mantle boundary of the Earth at a depth of approx. 2900 kilometres, temperatures of between 3000-4000 Kelvin and pressures of around 135 gigapascals (GPa) are assumed. This pressure corresponds to almost 14 tonnes per square millimetre. Credit: S. Lobanov, GFZ

Structural changes in ice as it passes through phase space: Formation of superionic ice

The researchers first produced ice VII or X from water at room temperature by increasing the pressure to several tens of Gigapascal (see the phase diagram). And then, at constant pressure, they increased the temperature by heating it with laser light. In the process, they observed how the crystalline ice structure changed: First, the oxygen and hydrogen atoms moved a little around their fixed positions. Then only the oxygen remained fixed and formed its own cubic crystal lattice. As the temperature rose, the hydrogen ionized, i.e. gave up its only electron to the oxygen lattice. Its atomic nucleus—a positively charged proton—then whizzed through this solid, making it electrically conductive. In this way, a hybrid of solid and liquid is created: Superionic ice.

Its existence was predicted on the basis of various models and has already been observed on several occasions under laboratory conditions. The scientists have now been able to synthesize and identify two superionic ice phases—ice XVIII and ice XX—and to delineate the pressure and temperature conditions of their stability. "Due to their distinct density and increased optical conductivity, we assign the observed structures to the theoretically predicted superionic ice phases," explains Lobanov.

Consequences for the explanation of the magnetic field of Uranus and Neptune

In particular, the phase transition to a conducting liquid has interesting consequences for the open questions surrounding the magnetic field of Uranus and Neptune, which presumably consist of more than sixty percent water. Their magnetic field is unusual in that it does not run quasi parallel and symmetrically to the axis of rotation—as it does on Earth—but is skewed and off-center. Models of its formation therefore assume that it is not generated—as on Earth—by the motion of molten iron in the core, but by a conductive water-rich liquid in the outer third of Uranus or Neptune.

"In the phase diagram, we can draw the pressure and temperature in the interiors of Uranus and Neptune. Here, the pressure can roughly be taken as a measure of the depth inside. Based on the refined phase boundaries we have measured, we see that about the upper third of both planets is liquid, but deeper interiors contain solid superionic ices. This confirms the predictions about the origin of the observed magnetic field," Lobanov sums up.

Outlook

The geophysicist emphasizes that further investigations to better clarify the inner structure and the magnetic field of the two gas planets will be carried out at the GFZ. Here, in addition to the diamond anvil cells already in use, there is both the corresponding high-pressure laboratory and the highly sensitive spectroscopic measuring equipment. Lobanov set up the latter as part of his funding as head of the Helmholtz Young Investigators Group CLEAR to investigate the phenomena of the deep Earth with unconventional ultra-fast time-resolved spectroscopy techniques.

More information: Vitali Prakapenka, Structure and properties of two superionic ice phases, Nature Physics (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41567-021-01351-8. www.nature.com/articles/s41567-021-01351-8

Journal information: Nature Physics

Provided by Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres