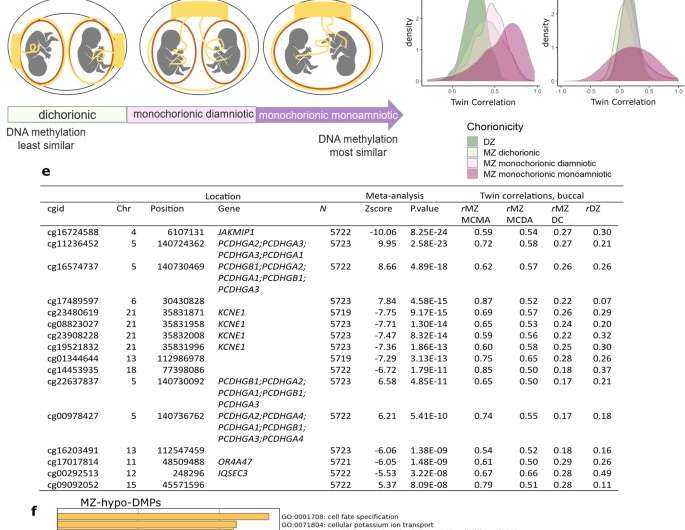

MZ twinning DMPs identified in a meta-analysis of data from 5723 twins. a Manhattan plot of the EWAS meta-analysis based on whole blood DNA methylation data from five twin cohorts (total sample size = 5723) that identified 834 MZ-DMPs. The red horizontal line denotes the epigenome-wide significance threshold (Bonferroni correction). Dark red dots highlight significant DMPs near centromeres. Orange dots highlight significant DMPs near telomeres. b Dichorionic (DC) MZ twins have separate chorions, amnions, and placentas. Monochorionic diamniotic (MCDA) MZ twins have separate amnions and a common chorion and placenta. Monochorionic monoamniotic (MCMA) have a common chorion, amnion, and placenta. It has been hypothesized that DC MZ twins result from separation soon after fertilization, whereas MC twins are thought to result from separation ≥3 days after fertilization, with MCMA twins arising later than MCDA twins. c Density plots of twin correlations for the differentially methylated positions in monozygotic twins (MZ-DMPs) identified in the EWAS meta-analysis illustrate that the overall distribution of twin correlations at MZ-DMPs show the following pattern: rMZ-MCMA > rMZ-MCDA > rMZ-DC. d Twin correlations for genome-wide autosomal methylation sites do not follow this pattern. MZ monozygotic twins, DZ dizygotic twins. e MZ-DMPs with larger correlations in monochorionic MZ twins compared to dichorionic MZ twins. The CpGs were selected by three criteria (1) rMZ-MCMA > rMZ-MCDA > rMZ-DC; (2) rMZ-MCDA > 0.5; (3) rMZ-DC < 0.2. cgid = Illumina CpG identifier. Chr = chromosome; rMZ-MCMA = correlation in monozygotic monochorionic monoamniotic pairs. rMZ-MCDA = correlation in monozygotic monochorionic diamniotic pairs. rMZ-DC = correlation in monozygotic dichorionic pairs. f–g Pathway enrichment analysis results based on the nearest genes of the 834 Bonferroni-significant MZ-DMPs identified in the meta-analysis. f Top enriched gene ontology (GO) pathways for MZ-hypo-DMPs (differentially methylated positions with a lower methylation level in monozygotic twins). The darker the color, the stronger the enrichment. g Top enriched gene ontology (GO) pathways for MZ-hyper-DMPs (differentially methylated positions with a higher methylation level in monozygotic twins). The darker the color, the stronger the enrichment. Credit: DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-25583-7

An international group of researchers has made a groundbreaking discovery that could lead to new insights into the blueprint of identical twins.

The findings of the study, published on September 28 in Nature Communications, represent a huge step forward in understanding identical twins. The study was led by twin researchers from the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The findings based on the Dutch twin cohort were replicated in three other cohorts, one of them being the Finnish Twin Cohort.

From the University of Helsinki, Professor Jaakko Kaprio and Academy Researcher Miina Ollikainen from the Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland FIMM contributed to the study.

Despite a century of amazing progress in most areas of science we still have no idea how identical (monozygotic—MZ) twins arise. In contrast we are making fast progress on understanding the biological origins of nonidentical twins, which run strongly in families, pointing to genetic influences.

Identical twins have unique epigenetic profile

In this study, instead of focusing on genomics, an epigenome wide association study was done. This led to an important discovery: epigenetic information in the chromosomes differs between identical twins and others. These epigenetic differences are not in the DNA code itself, but in small chemical marks associated with it.

Around the building blocks of DNA (the DNA code) are control elements that determine how genes are tuned and how strongly they are expressed. This is the so-called epigenome. A useful analogy is how the holding the shift key on a keyboard, can make the letter "a" become capitalized "A" allowing another level of regulation on how each letter or number on the keyboard can be displayed. Likewise, DNA methylation (like pressing the shift key) controls which genes are "on" and which genes are "off" in each cell of the body. The field that studies this tuning of genes is called epigenetics.

The researchers measured the level of methylation at more than 400,000 sites in the DNA of more than 6,000 twins. They found 834 locations in the DNA where the methylation level was different in identical twins than in non-twins. Many of these locations in the DNA are involved in functions in early embryonic development.

"The results points to unusual methylation patterns in genes involved in cell adhesion which might explain why there is spontaneous fission of an early developing embryo into two identical halves," said Miina Ollikainen.

Important breakthrough

"This is a very big discovery. The origin and birth of identical twins has always been a complete mystery. It is one of the few traits in which genetics plays no or very modest role. This is the first time that we have found a biological marker of this phenomenon in humans. The explanation appears not to lie in the genome, but in its epigenome," said Professor Dorret Boomsma of the Netherlands Twin Register who led the study.

In addition to insights into the fabrics of monozygotic twins, the results may lead to a better understanding of congenital abnormalities that occur more often in monozygotic twins in the future.

"A particularly surprising finding in this study is that we can determine from the epigenetic profile of a person whether he/she is an identical twin or has lost a monozygotic twin sibling early in pregnancy," said Professor Jaakko Kaprio.

More information: Jenny van Dongen et al, Identical twins carry a persistent epigenetic signature of early genome programming, Nature Communications (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-25583-7

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by University of Helsinki