New report: State of the science on western wildfires, forests and climate change

Exceptionally hot and dry weather this summer has fueled dozens of wildfires across the western U.S., spewing smoke across the country and threatening to register yet another record-breaking year. More than a century of fire exclusion has created dense forests packed with excess trees and brush that ignite and spread fires quickly under increasingly warm and dry conditions.

Scientists largely agree that reducing these fuels is needed to make our forests and surrounding communities more resilient to wildfires and climate change. But policy and action have not kept pace with the problem and suppressing fires is still the norm, even as megafires become more common and destructive.

Seeing the urgent need for change, a team of scientists from leading research universities, conservation organizations and government laboratories across the West has produced a synthesis of the scientific literature that clearly lays out the established science and strength of evidence on climate change, wildfire and forest management for seasonally dry forests. The goal is to give land managers and others across the West access to a unified resource that summarizes the best-available science so they can make decisions about how to manage their landscapes.

"Based on our extensive review of the literature and the weight of the evidence, the science of adaptive management is strong and justifies a range of time- and research-tested approaches to adapt forests to climate change and wildfires," said co-lead author Susan Prichard, a research scientist in the University of Washington's School of Environmental and Forest Sciences.

These approaches include some thinning of dense forests in fire-excluded areas, prescribed burning, reducing fuels on the ground, allowing some wildfires to burn in backcountry settings under favorable fuel and weather conditions, and revitalizing Indigenous fire stewardship practices. The findings were published Aug. 2 as an invited three-paper feature in the journal Ecological Applications.

The authors studied and reviewed over 1,000 published papers to synthesize more than a century of research and observations across a wide geographic range of western North American forests. The analysis didn't include rainforests in the Pacific Northwest or other wet forests where thinning and prescribed burning wouldn't be advised.

"The substantial changes associated with more than a century of fire exclusion jeopardize forest diversity and keystone processes as well as numerous other social and ecological values including quantity and quality of water, stability of carbon stores, air quality, and culturally important resources and food security," said co-lead author and UW researcher Keala Hagmann.

This ambitious set of articles was inspired by the reality that under current forest and wildfire management, massive wildfires and drought are now by far the dominant change agents of western North American forests. There is an urgent need to apply ecologically and scientifically credible approaches to forest and fire management at a pace and scale that matches the scope of the problem, the authors say.

Part of the solution involves addressing ongoing confusion over how to rectify the effects of more than a century of fire exclusion as the climate continues to warm. Land managers and policymakers recognize that the number and size of severe fires are rapidly increasing with climate change, but agreement and funding to support climate and wildfire adaptation are lagging.

To that end, these papers review the strength of the science on the benefits of adapting fire-excluded forests to a rapidly warming climate. The authors address 10 common questions, including whether management is needed after a wildfire, or whether fuel treatments (thinning, prescribed burning) work under extreme fire weather. They also discuss the need to integrate western fire science with traditional ecological knowledge and Indigenous fire uses that managed western landscapes for thousands of years.

-

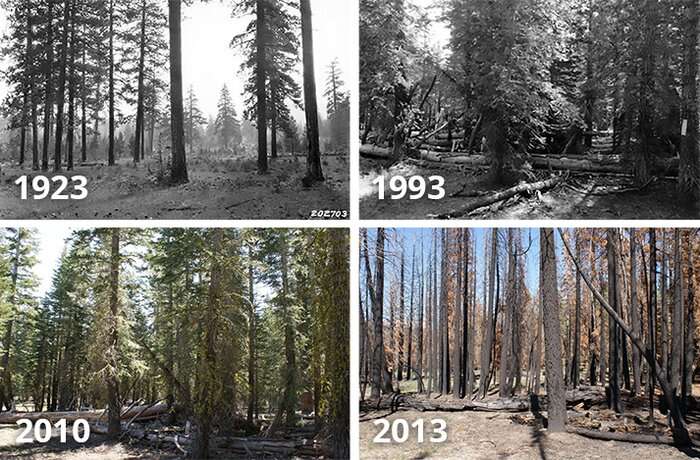

Forest change caused by fire suppression in Lassen Volcanic National Park in northeastern California, shown during four different years: 1923, 1993, 2010 and 2013. The forest burned severely in the 2012 Reading Fire. Historically, these forests burned about every 10 years at low to moderate severity until fire suppression was implemented in 1905. High surface fuel loads and development of a dense forest understory due to fire exclusion created conditions for the high severity Reading Fire in 2012. Credit: A.H. Taylor and A.E. Weislander -

An aerial photo showing untreated forestland (left) across the road from an area that has been thinned (right). Credit: John Marshall Photography -

A low-intensity prescribed burn to reduce fuels in a forest accustomed to wildfires. Credit: John Marshall Photography -

Fire crews work to control a low-intensity prescribed burn to reduce fuels in Ochoco National Forest in central Oregon. Credit: U.S. Forest Service-Pacific Northwest Region

Although climate change brings with it many uncertainties, the evidence supporting intentional forest adaptation is strong and broad based. The authors clearly demonstrate that lingering uncertainties about the future should no longer paralyze actions that can be taken today to adapt forests and communities to a warming climate and more fire.

"This collection represents a blending of scientific voices across the entire disciplinary domain," said co-lead author Paul Hessburg, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service and affiliate professor at the UW. "After reviewing the evidence, it is clear that the changes to forest conditions and fire regimes across the West are significant. The opportunity ahead is to adapt forests to rapidly changing climatic and wildfire regimes using a wide range of available, time-tested management tools."

More information: Paul F. Hessburg et al, Wildfire and climate change adaptation of western North American forests: a case for intentional management, Ecological Applications (2021). DOI: 10.1002/eap.2432

Journal information: Ecological Applications

Provided by University of Washington