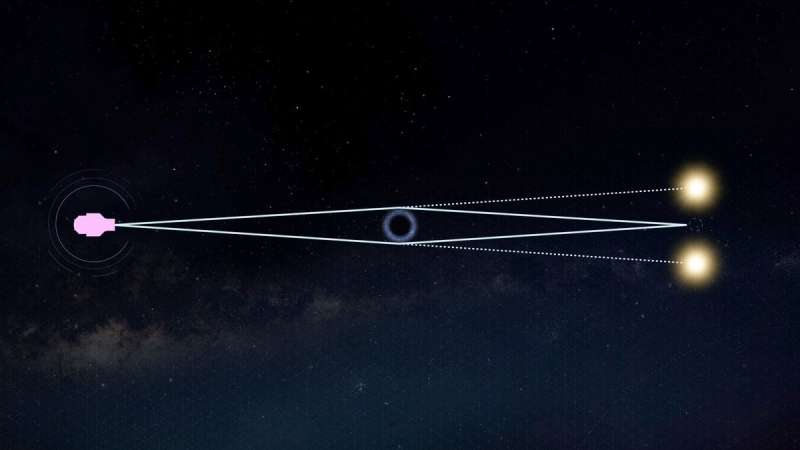

How microlensing around a black hole would work. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

In the past, we've reported about how the Roman Space Telescope is potentially going to be able to detect hundreds of thousands of exoplanets using a technique known as microlensing. Exoplanets won't be the only things it can find with this technique, though—it should be possible to find solitary black holes, as well.

Solitary black holes are unique, as most black holes that scientists have identified are those that are directly interacting with another object. However, those that are relatively small that could be roving around the galaxy by themselves, which would be almost impossible to detect, since they absorb all electromagnetic wavelengths.

Usually, these small black holes weigh around 10 times the weight of the sun. They form when a star dies and either goes supernova or collapses directly into a black hole, depending on its weight. If the black hole isn't surrounded by any gas or dust to absorb, it would then become essentially invisible to almost all instruments.

So far, scientists have found 20 of these stellar-mass black holes, but only because they are proximal to another astronomical object, making their gravitational force apparent in the companion object's movements.

The neat thing about the microlensing technique that Roman will use to detect planets is that any large gravitational field will cause the microlensing effect. So if Roman sees what appears to be a microlensing effect with no obvious source of mass, it is likely to be a black hole causing it.

In order to find the slight disturbances that would cause the microlensing, Roman will have to stare at hundreds of millions of stars for a very long time. But that is exactly what it is designed to do. With this additional data, scientists will be able to answer questions such as why solitary black holes only seem to have mass around 10 times that of the sun, or exactly how many stellar-mass black holes there are in the galaxy. The current estimate is around 100 million.

How to use gravitational lensing to detect black holes. Credit: NASA

No matter the answers to these questions, Roman will provide more data to inform conclusions on these questions and many others when it launches around 2025.

Provided by Universe Today