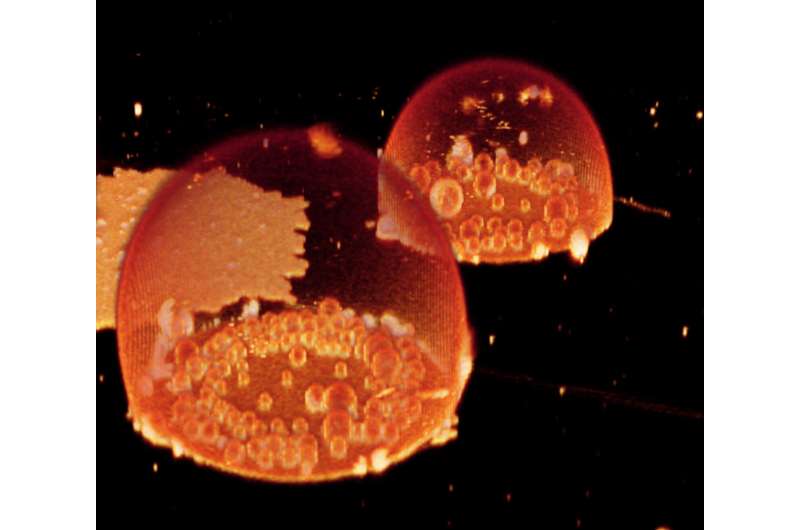

"Protocells" containing bubble-like compartments formed spontaneously on a mineral-like and encapsulated fluorescent dye. This could have been what happened 3.8 billion years ago when cells first began to form. Credit: Karolina Spustova

Scientists have long speculated about the features of our long-ago single-celled ancestors and the order in which those features came about. Bubble-like compartments are a hallmark of the superkingdom to which we and many other species, including yeast, belong. But the cells in today's superkingdom have a host of specialized molecules that help make and shape these bubbles inside our cells. Scientists wondered what came first: the bubbles or the shaping molecules? New research by Karolina Spustova, a graduate student, and colleagues in the lab of Irep Gözen at the University of Oslo, shows that with just a few key pieces these little bubbles can form on their own, encapsulate molecules, and divide without help. Spustova will present her research, which was published in the journal Small, on Wednesday, February 24 at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Biophysical Society.

Around 3.8 billion years ago, our single-cell ancestor came to be. It would have preceded not only complex organisms in our superkingdom, but also the more basic bacteria. Whether this "protocell" had bubble-like compartments is a mystery. For a long time, scientists thought that these lipid bubbles were something that set our superkingdom apart from other organisms, like bacteria. Because of this, scientists thought that these compartments might have formed after bacteria came to exist. But recent research has shown that bacteria have specialized compartments, too, which led Gözen's research team to wonder—could the protocell that came before bacteria and our ancestors have them? And if so, how could they have formed?

The research team mixed the lipids that form modern cell compartments, called phospholipids, with water and put the mix on a mineral-like surface. They found that large bubbles spontaneously formed, and inside those bubbles were smaller ones. To test whether those compartments could encapsulate small molecules, as they would need to do to have specialized functions, the team added fluorescent dyes. They observed that these bubbles were able to take up and hold onto the dyes. They also saw instances where the bubbles split, leaving smaller "daughter" bubbles, which, according to Spustova, is "something like simple division of the first cells." All of this occurred without any molecular machines like those in our cells, and without added energy.

The idea that this could have happened on Earth 3.8 billion years ago is not inconceivable. Gözen explained that water would have been plentiful, along with silica and aluminum, "which we used in our study, and are present in natural rocks." Research shows that the phospholipid molecules could have been synthesized under early Earth conditions or reached Earth with meteorites. Gözen says, "These molecules are believed to have reached sufficient concentrations to form phospholipid compartments." So it is possible that the ancient "protocell" that came before all the organisms currently on Earth had everything it needed for bubble-like compartments to form spontaneously.

More information: Karolina Spustova et al. Subcompartmentalization and Pseudo‐Division of Model Protocells, Small (2020). DOI: 10.1002/smll.202005320

Journal information: Small

Provided by Biophysical Society