The world's oldest story? Astronomers say global myths about 'seven sisters' stars may reach back 100,000 years

In the northern sky in December is a beautiful cluster of stars known as the Pleiades, or the "seven sisters." Look carefully and you will probably count six stars. So why do we say there are seven of them?

Many cultures around the world refer to the Pleiades as "seven sisters," and also tell quite similar stories about them. After studying the motion of the stars very closely, we believe these stories may date back 100,000 years to a time when the constellation looked quite different.

The sisters and the hunter

In Greek mythology, the Pleiades were the seven daughters of the Titan Atlas. He was forced to hold up the sky for eternity, and was therefore unable to protect his daughters. To save the sisters from being raped by the hunter Orion, Zeus transformed them into stars. But the story says one sister fell in love with a mortal and went into hiding, which is why we only see six stars.

A similar story is found among Aboriginal groups across Australia. In many Australian Aboriginal cultures, the Pleiades are a group of young girls, and are often associated with sacred women's ceremonies and stories. The Pleiades are also important as an element of Aboriginal calendars and astronomy, and for several groups their first rising at dawn marks the start of winter.

Close to the Seven Sisters in the sky is the constellation of Orion, which is often called "the saucepan" in Australia. In Greek mythology Orion is a hunter. This constellation is also often a hunter in Aboriginal cultures, or a group of lusty young men. The writer and anthropologist Daisy Bates reported people in central Australia regarded Orion as a "hunter of women," and specifically of the women in the Pleiades. Many Aboriginal stories say the boys, or man, in Orion are chasing the seven sisters—and one of the sisters has died, or is hiding, or is too young, or has been abducted, so again only six are visible.

The lost sister

Similar "lost Pleiad" stories are found in European, African, Asian, Indonesian, Native American and Aboriginal Australian cultures. Many cultures regard the cluster as having seven stars, but acknowledge only six are normally visible, and then have a story to explain why the seventh is invisible.

How come the Australian Aboriginal stories are so similar to the Greek ones? Anthropologists used to think Europeans might have brought the Greek story to Australia, where it was adapted by Aboriginal people for their own purposes. But the Aboriginal stories seem to be much, much older than European contact. And there was little contact between most Australian Aboriginal cultures and the rest of the world for at least 50,000 years. So why do they share the same stories?

Barnaby Norris and I suggest an answer in a paper to be published by Springer early next year in a book titled Advancing Cultural Astronomy, a preprint for which is available here.

All modern humans are descended from people who lived in Africa before they began their long migrations to the far corners of the globe about 100,000 years ago. Could these stories of the seven sisters be so old? Did all humans carry these stories with them as they traveled to Australia, Europe, and Asia?

-

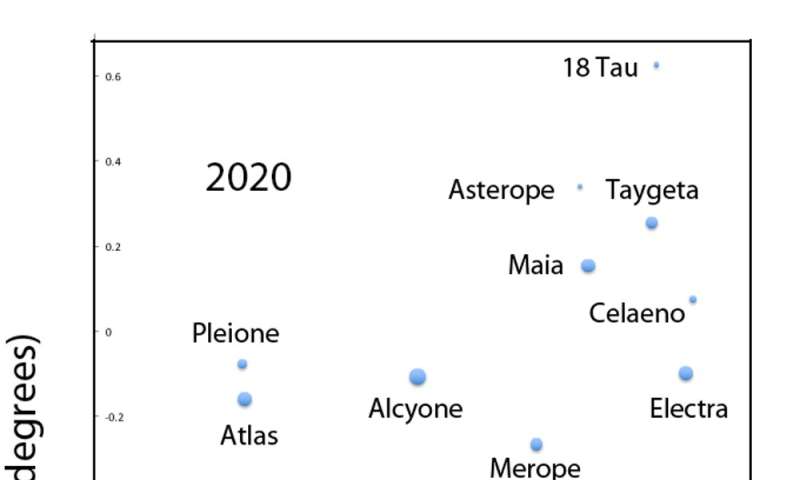

The positions of the stars in the Pleiades today and 100,000 years ago. The star Pleione, on the left, was a bit further away from Atlas in 100,000 BC, making it much easier to see. Credit: Ray Norris -

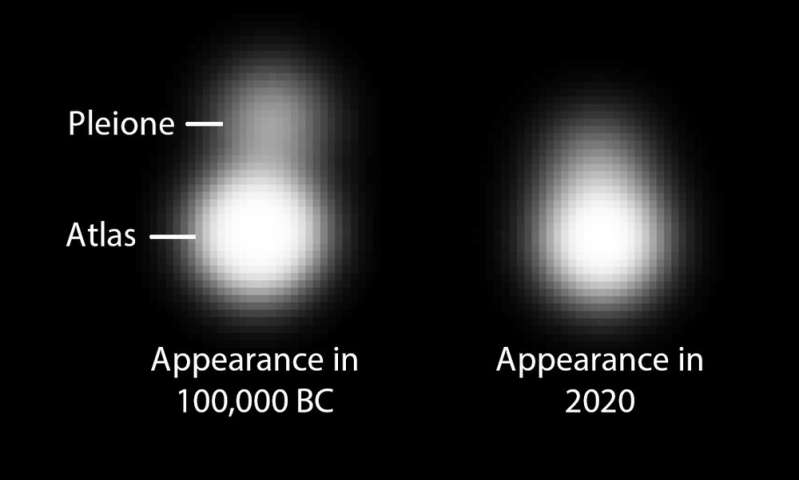

A simulation showing hows the stars Atlas and Pleione would have appeared to a normal human eye today and in 100,000 BC. Credit: Ray Norris

Moving stars

Careful measurements with the Gaia space telescope and others show the stars of the Pleiades are slowly moving in the sky. One star, Pleione, is now so close to the star Atlas they look like a single star to the naked eye.

But if we take what we know about the movement of the stars and rewind 100,000 years, Pleione was further from Atlas and would have been easily visible to the naked eye. So 100,000 years ago, most people really would have seen seven stars in the cluster.

We believe this movement of the stars can help to explain two puzzles: the similarity of Greek and Aboriginal stories about these stars, and the fact so many cultures call the cluster "seven sisters" even though we only see six stars today.

Is it possible the stories of the Seven Sisters and Orion are so old our ancestors were telling these stories to each other around campfires in Africa, 100,000 years ago? Could this be the oldest story in the world?

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()