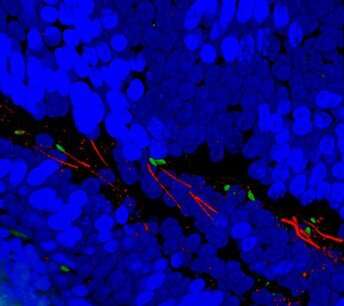

Credit: Three-dimensional image showing the head (green) and tail (red) of sperm cells travelling towards the fertilisation site (to the left side of the image) in the reproductive tract (blue cells) of a female mouse. Credit: Lukas Ded (CC BY 4.0)

A protein called CatSper1 may act as a molecular 'barcode' that helps determine which sperm cells will make it to an egg and which are eliminated along the way.

The findings in mice, published recently in eLife, have important implications for understanding the selection process that sperm cells undergo after they enter the female reproductive tract, a key step in reproduction. Learning more about these processes could lead to the development of new approaches to treating infertility.

"Male mammals ejaculate millions of sperm cells into the female's reproductive tract, but only a few arrive at the egg," explains senior author Jean-Ju Chung, Assistant Professor of Cellular & Molecular Physiology at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, US. "This suggests that sperm cells are selected as they travel through the tract and excess cells are eliminated. But most of our knowledge about fertilization in mammals has come from studying isolated sperm cells and eggs in a petri dish—an approach that doesn't allow us to see what happens during the sperm selection and elimination processes."

To address this challenge, Chung and colleagues, including lead author Lukas Ded, who was a postdoctoral fellow in the Chung laboratory when the study was carried out, devised a new molecular imaging strategy to observe the sperm selection process within the reproductive tract of mice. Using this technique, and combining it with more traditional molecular biology studies, the team revealed that a sperm protein called CatSper1 must be intact for a sperm cell to fertilize an egg.

The CatSper1 protein is one of four proteins that create a channel to allow calcium to flow into the membrane surrounding the tail of the sperm. This channel is essential for sperm movement and survival. If this protein is lopped off in the reproductive tract, the sperm never makes it to the egg and dies. "This highlights CatSper1 as a kind of barcode for sperm selection and elimination in the female reproductive tract," says Chung.

The findings, and the new imaging platform created by the team, may enable scientists to learn more about the steps in the fertilization process and what happens afterwards, such as when the egg implants into the mother's uterus.

"Our study opens up new horizons to visualize and analyze molecular events in single sperm cells during fertilization and the earliest stages of pregnancy," Chung concludes. "This and further studies could ultimately provide new insights to aid the development of novel infertility treatments."

More information: Lukas Ded et al, 3D in situ imaging of the female reproductive tract reveals molecular signatures of fertilizing spermatozoa in mice, eLife (2020). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.62043

Journal information: eLife

Provided by eLife