Painstaking race against time to uncover Viking ship's secrets

Inch by inch, they gently pick through the soil in search of thousand-year-old relics. Racing against onsetting mould yet painstakingly meticulous, archaeologists in Norway are exhuming a rare Viking ship grave in hopes of uncovering the secrets within.

Who is buried here? Under which ritual? What is left of the burial offerings? And what can they tell us about the society that lived here?

Now reduced to tiny fragments almost indistinguishable from the turf that covers it, the 20-metre (65-foot) wooden longship raises a slew of questions.

The team of archaeologists is rushing to solve at least some of the mystery before the structure is entirely ravaged by microscopic fungi.

It's an exhilarating task: there hasn't been a Viking ship to dig up in more than a century.

The last was in 1904 when the Oseberg longship was excavated, not far away on the other side of the Oslo Fjord, in which the remains of two women were discovered among the finds.

"We have very few burial ships," says the head of the dig, Camilla Cecilie Wenn of the University of Oslo's Museum of Cultural History.

"I'm incredibly lucky, few archaeologists get such an opportunity in their career."

Under a giant grey and white tent placed in the middle of ancient burial grounds near the southeastern town of Halden, a dozen workers in high visibility vests kneel or lie on the ground, examining the earth.

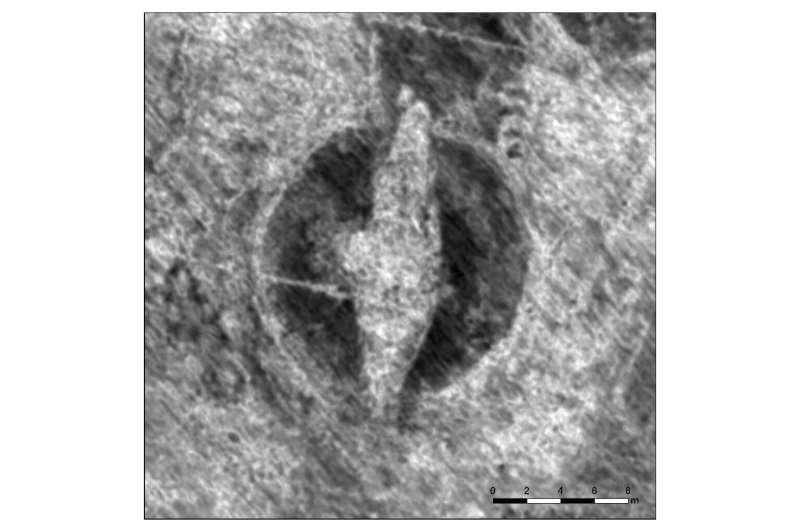

Buried underground, the contours of the longship were detected in 2018 by geological radar equipment, as experts searched the known Viking site.

When the first test digs revealed the ship's advanced state of decomposition, the decision was taken to quickly excavate it.

Viking VIP

So far, only parts of the keel have been dug out in reasonable condition.

Analyses of the pieces have determined that the ship was probably raised on land around the ninth century, placed in a pit and buried under a mound of earth as a final resting place.

But for whom? "If you're buried with a ship, then it's clear you were a VIP in your lifetime," Wenn says.

A king? A queen? A Viking nobleman, known as a jarl? The answer may lie in the bones or objects yet to be found—weapons, jewels, vessels, tools, etc—that are typical in graves from the Viking Age, from the mid-eighth to mid-11th centuries.

The site has however been disturbed several times, accelerating the ship's disintegration and reducing the chance of finding relics.

At the end of the 19th century, the burial mound was razed to make space for farmland, entirely destroying the upper part of the hull and damaging what is believed to have been the funeral chamber.

It's also possible that the grave may have been plundered long before that, by other Vikings keen to get their hands on some of the precious burial offerings and to symbolically assert their power and legitimacy.

Animal bones

So far the archaeologists' bounty is pretty meagre: lots of iron rivets used for the boat's assembly, most heavily corroded over time, as well as a few bones.

"These bones are too big to be human," says field assistant Karine Fure Andreassen, as she leans over a large, orange-tinged bone.

"This is not a Viking chief we're looking at unfortunately, it's probably a horse or cattle."

"It's a sign of power. You were so rich that an animal could be sacrificed to be put in your grave," she explains.

Beside the tent, Jan Berge looks like he's panning for gold. He's sifting soil and spraying it with water in hopes of finding a little nugget from the past.

"Make an exceptional find? I doubt it," admits the archaeologist. "The most precious items have probably already been taken. And anything made of iron or organic material has eroded over time or completely disappeared."

But Berge, whose big bushy beard gives him the air of a Viking, is not easily discouraged.

"I'm not here for a treasure hunt," he says. "What interests me is finding out what happened here, how the funeral was carried out, how to interpret the actions of the time."

Glamorous and worldly: Five things to know about Vikings

In popular culture they're depicted as ruthless warriors who pillaged and plundered. That reputation is not totally undeserved, but is only part of the picture. Here are five things to know about Vikings.

Where does their name come from?

Like many things about them, the etymology of the word "viking" is uncertain.

In Old Norse, an old Scandinavian language, the word appears as "vikingr", which designates a person, while "viking" designates a practice.

"The Scandinavians never spoke of themselves as Vikings, as an identity for anybody Scandinavian. The word rather meant an activity, to go raiding, or a person who was doing that," explains Jan Bill, a professor of Viking archaeology and curator of Oslo's Viking Ship Museum.

"But today, practice is to use 'Viking' to describe anybody Scandinavian from the Viking period," he adds, referring to the period from around the mid-eighth to mid-11th centuries.

Exposed to cannabis and Buddha

Apart from their pillaging, the Vikings were big tradesmen who forged a vast network of contacts from the Caspian Sea to Greenland.

It has been debated for years, but it is very likely that Vikings landed in America around the year 1,000, or five centuries before Christopher Columbus.

Some objects recovered from ship graves—three such ships are on display in very good condition at the Oslo museum—bear witness to the rich and varied nature of their contacts.

Among the numerous objects is a small leather bag containing cannabis, found on one of the two women buried with the longship dug up at Oseberg.

"The seeds may have been for recreational or medicinal purposes, or to grow hemp plants whose fibres were used for textiles and rope," says Jan Bill.

Other finds at various Viking sites include textiles and beads from the Orient, as well as coins from the Arab world—often broken into pieces as the Vikings didn't use them for currency but rather for their weight in silver and other precious metals.

A bronze Buddha dating back to this period was also found on the Swedish island of Helgo.

'Drakkar' or not 'drakkar'?

The word "drakkar" is sometimes purported to be a Viking-era word for a longship, which occasionally featured an ornamental dragon on the bow.

But some historians insist that the term is as recent as the 19th century, inspired by the modern Swedish word for dragon, "drake" in singular and "drakar" in plural.

That word is similar, but not exactly the same, as the word used in Old Norse.

"There are actually seven instances of ships being called 'dreki', or 'drekar' in plural, in poems from the Viking Age," says Jan Bill.

"It was not a technical term, though, rather poetic."

Historians do however agree that light longships, powered by oars and/or sails, were known for their speed and flexibility, capable of crossing oceans and, thanks to their shallow draught, sailing upriver.

The anti-Hagar

The famous American comic strip Hagar the Horrible depicts a heavy red-bearded Viking with a horned helmet and shaggy tunic.

But according to experts, the Vikings were more glamorous than that.

"Their clothing was very colourful. They loved jewellery and bling," says archaeologist Camilla Cecilie Wenn of the University of Oslo's Museum of Cultural History.

"Far from the drab style in which they're portrayed, they spent a lot of time on their appearance. They washed and brushed their hair and beards regularly," she says.

And the horned helmet? "A modern invention from the Romantic period," Jan Bill says dismissively.

"None of the few helmets found from the Viking Age, or the preceding centuries, have horns."

The "mistake" is attributed to costume designer Carl Emil Doepler, who in 1876 added horns to the warriors' helmets in a performance of Richard Wagner's Ring Cycle opera, inspired by Nordic mythology.

Clinking to toast?

Urban legend also attributes the modern act of clinking drinking glasses to the Vikings.

They purportedly clinked their mugs so violently that some of their beer or mead would slosh into the other person's mug, thereby ensuring that their drink wasn't poisoned.

But there's no evidence to support that theory.

And contrary to popular belief, Vikings did not drink out of their enemies' skulls either.

© 2020 AFP