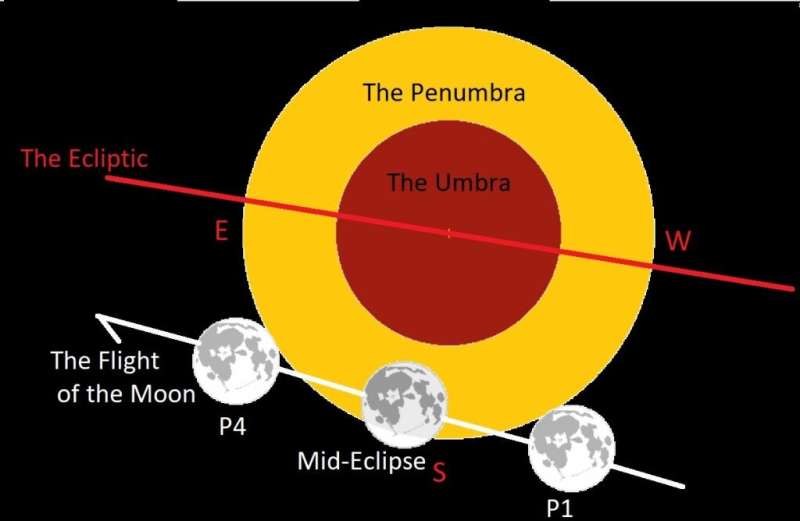

The Moon vs. the shadow of the Earth during Monday morning’s eclipse. Adapted from NASA/GSFC/F. Espenak graphic

Howling at the Moon Sunday night? Sunday night into Monday morning November 30th features not only the penultimate Full Moon for 2020, but the final lunar eclipse of the year, with a penumbral eclipse of the Moon.

The eclipse is a subtle penumbral eclipse, the fourth and final of four such eclipses in 2020 and the final lunar eclipse for the decade. The Moon won't turn blood-red like during a total lunar eclipse: at most, expect a fine tea-colored shading to drape to Moon, with perhaps a ragged discoloration on the northwestern limb of the Moon near mid-eclipse.

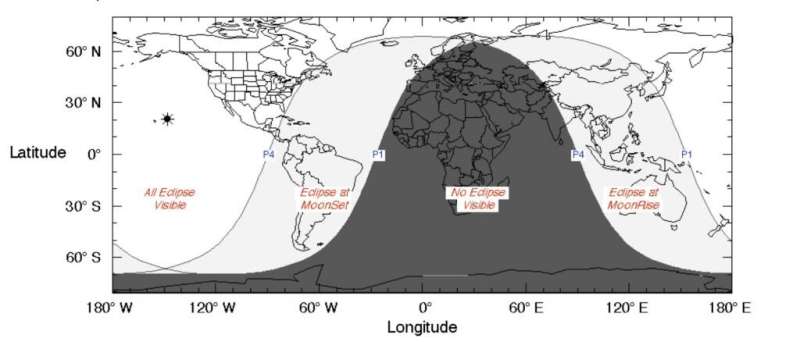

The eclipse is visible in its entirety from North America, while South America sees the eclipse in progress at sunrise/moonset, and eastern Asia and Australia sees the eclipse underway at sunset/moonrise. Hawaii gets the very best view, with the eclipsed Moon very near the zenith.

Times for the eclipse are:

- The Moon starts to enter the penumbral shadow of the Earth (P1) at 7:32 Universal Time (UT)/2:32 AM Eastern Standard Time (EST) on Monday, November 30th.

- Mid-eclipse occurs at 9:44 UT/4:44 AM EST.

- The Moon exits the Earth's penumbral shadow (P4) at 11:53 UT/6:53 AM EST.

The entire eclipse lasts 4 hours and 21 minutes… but the best time to take a look and see perhaps a light shading on the Moon is around mid-eclipse, when the Moon is 83% immersed in the penumbra of the Earth. The Moon juuuuust misses the inner dark umbra of the Earth's shadow by less than 10' arcminutes.

The visibility footprint for Monday’s eclipse. Credit: NASA/GSFC/Fred Espenak

This eclipse also marks the start of the final eclipse season for 2020. If the orbit of the Moon was aligned with the ecliptic flight of the Earth around the Sun, we would see an eclipse every 29.5 day synodic period: one lunar and one solar eclipse at Full and New Moon, respectively. Since the orbit of the Moon is tilted just over five degrees relative to the ecliptic, we have to wait until the intersection nodes are lined up for an eclipse season to occur, something that happens roughly twice a year. This also means that eclipses occur in lunar-solar pairs. In the case of the upcoming eclipse season, Monday's penumbral lunar eclipse is followed by a total solar eclipse spanning the southern tip of South America on December 14th.

Tales of the Saros

What's more, lunar and solar eclipses are members of larger 18 year, 11 day and 8 hour-long period known as a saros. This works out because 223 synodic lunations (the period of time it takes the Moon to return to like phase, i.e. Full-to-full or New-to-New) very nearly equals a saros. This also means that successive eclipses with very similar circumstances occur one saros apart, with the visibility path shifted 120 degrees in longitude westward. Several saroses—both lunar and solar—are in play on any given year. In the case of Monday's penumbral, this eclipse is member 58 of 73 eclipses in lunar saros series 116, which started in 933 AD on March 11th, and runs all the way out to 2291. Saros 116 also produced its last total lunar eclipse on July 11th, 1786 and is now on its way out the door, with a final shallow penumbral eclipse occurring on May 14, 2291.

Why do penumbrals occur? Why doesn't the Earth cast one distinct, sharp shadow out into space? This dual shadow has to do with the nature of light, and the fact that the Sun isn't a point source: it's actually visually very nearly the apparent size of of the Moon as seen from the Earth, as witnessed during a total solar eclipse. You see this secondary shadow effect daily, in places like a room lit only from a window off to one side: once you know to look for them, penumbral shadows are literally everywhere.

Here's another way to think of it: when you're witnessing a partial solar eclipse, you're also in the penumbral shadow of the Moon. Likewise, standing on the nearside of the Moon on Monday morning and looking back at the Earth (with proper eye protection, of course), you would see a partial solar eclipse.

Turn's out, a newcomer will indeed be on the Moon, assuming it lands successfully: China's Chang'e 5 sample return mission, set to land at Mon Rümker in the Oceanus Procellarum region this weekend. There's no word if the team is planning on imaging the partial solar eclipse (or even has to capability to do so) but this possible view from the surface of the Moon would be a first.

Monday’s eclipse… as seen from the Moon. Credit: Stellarium

Here's a fun naked eye observation to carry out during a penumbral eclipse: take a close at the Full Moon right near mid- 'penumbralarity…' would you notice something was afoot, if you didn't know better? Can you spy the ragged edge of the umbra, trying in vain to gobble up the Moon? Perhaps a lux or color meter (common on many smartphones these days) might sense the slight difference in brightness and tint during a penumbral eclipse.

A more straight-forward way to 'see' the eclipse is to simply image the Moon before, during and after the eclipse, using the exact same camera and settings… does the mid-eclipse photo look noticeably different to you?

Fear not: the total lunar eclipse drought is almost over. While 2021 features only four eclipses (the minimum that occur on a calendar year, which must be 2 lunar and 2 solar) we do indeed have a total lunar eclipse on May 26th, favoring the Pacific Rim region.

If skies are clear, be sure to set your alarm for the 'penultimate penumbral eclipse," of 2020.

Source Universe Today