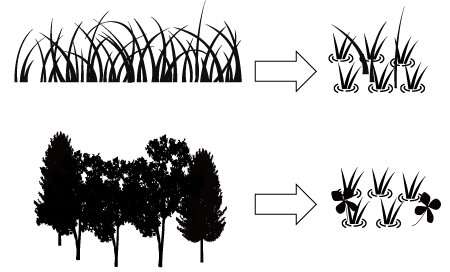

Rice paddies which were originally wetland are able to provide a new home for the original wetland plant species that were present. Conversely, paddies which were not originally wetland are a better home for non-wetland species. Credit: Tokyo Metropolitan University

Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University studied the biodiversity of wetland plants over time in rice paddies in the Tone River basin, Japan. They found that paddies that were more likely to have been wetland previously retained more wetland plant species. On the other hand, land consolidation and agricultural abandonment were both found to impact biodiversity negatively. Their findings may one day inform conservation efforts and promote sustainable agriculture.

The Asian monsoon region is home to a vast number of rice paddies. Not only have they fed its billions of inhabitants for centuries, they are also an important part of the ecosystem, home to a vast array of wetland plant species. But as the population grows and more agricultural land is required, their sheer scale and complexity beg an important question: What is their environmental impact?

A team from Tokyo Metropolitan University led by Associate Professor Takeshi Osawa and their collaborators have been studying how rice paddies affect local plant life. In their most recent work, they investigated the biodiversity of wetland plants in rice paddies around the Tone River basin Japan. The Tone River is Japan's second longest river, and runs through the 170,000 square kilometer expanse of the Kanto plains. Previous studies have looked at how a particular species or group of species fare in different conditions. Instead, the team turned their attention to the range of species that make up the plant community, with a particular focus on the number of wetland and non-wetland species present. Changes were tracked over time using extensive survey data from 2002, 2007 and 2012.

They found that not all rice paddies are equal when it comes to how well they support original wetland species. In fact, there was a correlation between how likely it was that the land was wetland before it was put to agricultural use, and the number of wetland species that were retained over time. Here, the team measured this using flow accumulation values (FAVs) for different plots of land, a simple metric showing how easily water could accumulate. Importantly, this kind of approach might help researchers to predict how amenable new rice paddies are to the local wetland flora by calculating a simple number using the local terrain. However, they also found that things like land consolidation and agricultural abandonment could also have a negative impact. The emerging story is that both current human use and original geographical conditions play an important role in deciding how amenable rice paddies are for the original wetland ecosystem.

The team believes that the same approach could be applied to different locations such as plantation forests which were (or were not) originally woodland. After all, many nations are turning to large scale tree planting to offset carbon emissions. The ability to systematically assign how new land usage might impact local ecosystems could greatly help restoration and conversation efforts.

More information: Takeshi Osawa et al, Paddy fields located in water storage zones could take over the wetland plant community, Scientific Reports (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-71958-z

Journal information: Scientific Reports

Provided by Tokyo Metropolitan University