In Malawi, South East Africa, this pest threatens the food supply of thousands of people. The insect should not be confused with the greenhouse whitefly Trialeurodes vaporariorum, which is more frequently found in Europe. Credit: Daniel G. Vassão

When attacking crucifers, the sap-sucking whitefly Bemisia tabaci can activate the chemical defenses of these plants. In a new study, an international team of researchers demonstrated that the pest is able to render a large proportion of the plant toxins harmless by binding surplus sugar to them. The whitefly thus deploys a completely new and until now undescribed detoxification mechanism to defuse the plants' defenses, which could explain the success of this major agricultural pest. The study is published in Nature Chemical Biology.

Worldwide dreaded crop pest of hundreds of plant species

Whiteflies are a family of sap-sucking insects that feed on the sugar-containing phloem of plants. The silverleaf whitefly Bemisia tabaci is particularly widespread worldwide and is greatly feared as an agricultural pest. Strictly speaking, it is not a single species, but a complex of about two dozen barely distinguishable species.

The actual damage to the plants occurs when the insects excrete sweet honeydew, which causes fungi to colonize the plants, and from the variety of plant viruses transmitted by the insects. For researchers studying the detoxification mechanisms of plant pests, Bemisia tabaci is a particularly interesting study system.

"This pest is perhaps one of, if not the most, successful phloem feeding insect in the world, found on hundreds of different species of plants to date. It encounters a variable landscape of chemical defense compounds in its diet," says Michael Easson, one of the two first authors of the study, who is a doctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology. For this reason, he teamed up with an international research team, in which the Hebrew University of Jerusalem plays a key role, to find out what makes Bemisia tabaci such a successful pest insect and how it deals with the chemical defense of its food plants.

The team around project group leader Daniel Vassão in the Department of Biochemistry at the Max Planck Institute has been studying detoxification mechanisms in different herbivores for several years. Of particular interest is how insects defuse the so-called mustard oil bomb of crucifers: This plant defense mechanism consists of two components, glucosinolates and the enzyme myrosinase, which are stored in different plant cells.

If plant tissue is damaged by herbivores, the enzyme cleaves off glucose sugars from the glucosinolates and toxic mustard oils are formed. Since sap-sucking insects do not chew leaf tissue and only cause minor tissue damage with their stylets, the narrow mouthparts they use to drink phloem, it was previously assumed that this defense mechanism plays only a minor role in the plants' protection against whiteflies or aphids. However, recent research has shown that not only chewing but also sucking insects can activate the mustard oil bomb.

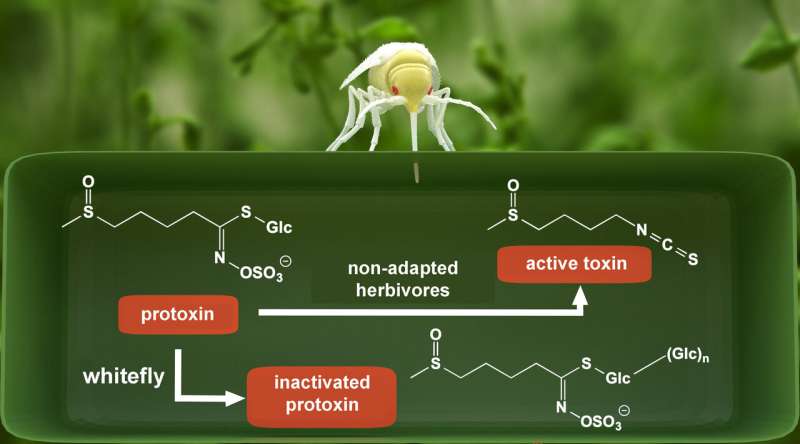

The protoxin (glucosinolate) is inactivated when an additional glucose group is bound to it. In comparison, the protoxin is converted into an active toxin (mustard oil) in non-adapted herbivores Credit: Kimberly Falk

A novel detoxification pathway

The scientists used the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, a cruciferous plant whose defense is also based on glucosinolates to study the metabolism of whiteflies in more detail. They especially analyzed the honeydew, the sugar-containing secretion of many sap-sucking insects, by means of chemical analyses and isotope labeling of individual chemical compounds. The researchers were surprised that the defense mechanism of Arabidopsis thaliana was actually activated by the whitefly as they found toxic mustard oils. However, they also discovered that the biochemical pathway leading to detoxification is a completely novel type of reaction in which sugar from the phloem is used to defuse plant toxins. "This reaction costs these insects basically nothing, as this sugar is in such surplus and has to be secreted as honeydew anyway," says study leader Daniel Vassão.

The detoxification process is based on a simple reaction in which sugar in the form of a glucose group is bound to another sugar that is already part of the glucosinolate. The researchers showed that the resulting new chemical product cannot be activated by the plant enzyme, probably because it is too bulky.

For this novel glucosylation pathway, the researchers were able to identify enzymes in Bemisia tabaci that catalyze the chemical reaction. They were amazed at the diversity of the detoxification toolbox of this insect. Although they focused on only one single class of plant defenses, the glucosinolates, they have already found at least three independent pathways for detoxification. "It will be interesting to see how general these detoxification pathways are and whether the whitefly also has specific detoxification pathways for other plant defensive compounds in its repertoire, and which enzymes control these processes," says Vassão.

More information: Easson et al., Glucosylation prevents plant defense activation in phloem-feeding insects, Nature Chemical Biology (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41589-020-00658-6, www.nature.com/articles/s41589-020-00658-6

Journal information: Nature Chemical Biology

Provided by Max Planck Society