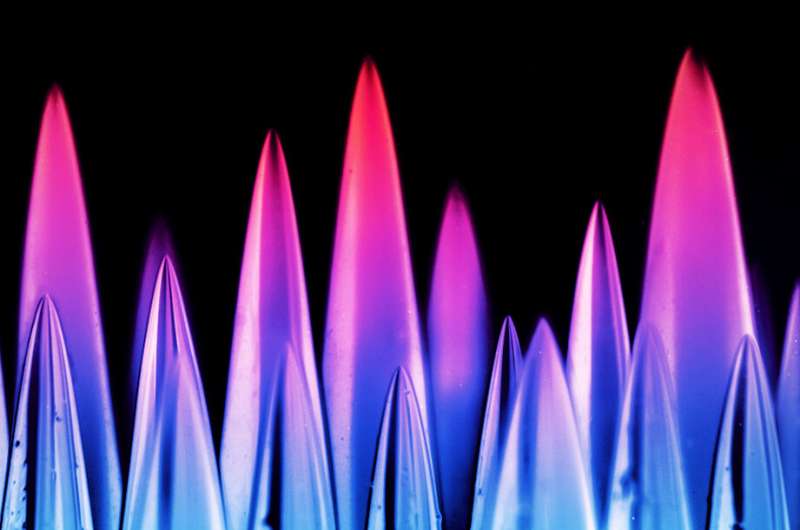

This false-color photograph shows a "forest" of many candy pinnacles that have been dissolved in water. The candy was initially a solid block containing pores, which the dissolving process has reshaped into a bed-of-nails formation. Credit: NYU's Applied Mathematics Lab

Stone forests—pointed rock formations resembling trees that populate regions of China, Madagascar, and many other locations worldwide—are as majestic as they are mysterious, created by uncertain forces that give them their shape.

A team of scientists has now shed new light on how these natural structures are created. Its research, reported in the latest issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), also offers promise for the manufacturing of sharp-tipped structures, such as the micro-needles and probes needed for scientific research and medical procedures.

"This work reveals a mechanism that explains how these sharply pointed rock spires, a source of wonder for centuries, come to be," says Leif Ristroph, an associate professor at New York University's Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences and one of the paper's co-authors. "Through a series of simulations and experiments, we show how flowing water carves ultra-sharp spikes in landforms."

The researchers, who included Michael Shelley, a professor at the Courant Institute, note that the study also illuminates a mechanism that explains the prevalence of sharply pointed rock spires in karst—a topography formed by the dissolution of rocks, such as limestone.

This video shows an experiment in which a dissolving block of candy develops into an array of sharp spikes. The block starts out with internal pores and is entirely immersed under water, where it dissolves and becomes a "candy forest" before collapsing. Credit: NYU's Applied Mathematics Lab

In their study, the scientists simulated the formation of these pinnacles over time through a mathematical model and computer simulations that took into account how dissolving produces flows and how these flows also affect dissolving and thus reshaping of a formation.

This video shows a side-by-side comparison of the shape development of a single dissolving pillar from experiment and simulation. Both methods show that an initially smooth apex is carved into an ultra-sharp spike. Credit: NYU's Applied Mathematics Lab

To confirm the validity of their simulations, the researchers conducted a series of experiments in NYU's Applied Mathematics Lab. Here, the scientists replicated the formation of these natural structures by creating sugar-based pinnacles, mimicking soluble rocks that compose karst and similar topographies, and submerging them in tanks of water. Interestingly, no flows had to be imposed, since the dissolving process itself created the flow patterns needed to carve spikes.

The experimental results reflected those of the simulations, thereby supporting the accuracy of the researchers' model (see "Video2ExperimentSimulation" in the below drive). The authors speculate that these same events happen—albeit far more slowly—when minerals are submerged under water, which later recedes to reveal stone pinnacles and stone forests.

More information: Jinzi Mac Huang el al., "Ultra-sharp pinnacles sculpted by natural convective dissolution," PNAS (2020). www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2001524117

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by New York University