Researchers recently learned of the unique weight-saving adaptation to dinosaur bone that enabled 8,000 pound dinosaurs like hadrosaurs to move easily. Credit: Illustration by Karen Carr

Weighing up to 8,000 pounds, hadrosaurs, or duck-billed dinosaurs were among the largest dinosaurs to roam the Earth. How did the skeletons of these four-legged, plant-eating dinosaurs with very long necks support such a massive load?

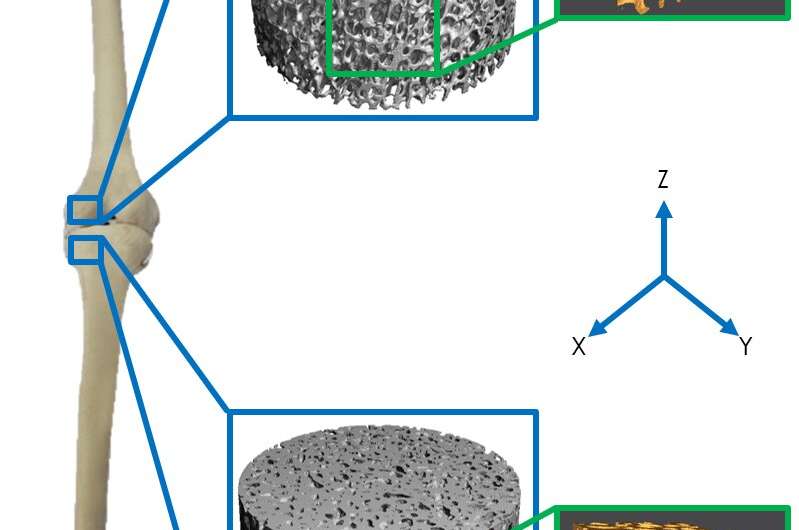

New research recently published in PLOS ONE offers an answer. A unique collaboration between paleontologists, mechanical engineers and biomedical engineers revealed that the trabecular bone structure of hadrosaurs and several other dinosaurs is uniquely capable of supporting large weights, and different than that of mammals and birds.

"The structure of the trabecular, or spongy bone that forms in the interior of bones we studied is unique within dinosaurs," said Tony Fiorillo, SMU paleontologist and one of the study authors. The trabecular bone tissue surrounds the tiny spaces or holes in the interior part of the bone, Fiorillo says, such as what you might see in a ham or steak bone.

"Unlike in mammals and birds, the trabecular bone does not increase in thickness as the body size of dinosaurs increase," he says. "Instead it increases in density of the occurrence of spongy bone. Without this weight-saving adaptation, the skeletal structure needed to support the hadrosaurs would be so heavy, the dinosaurs would have had great difficulty moving."

An interdisciplinary team of researchers that compared CT scans of bones of living mammals with fossil bones of dinosaurs found that the trabecular bone structure of hadrosaurs and several other dinosaurs is uniquely capable of supporting large weights and different than that of mammals and birds. Figure 1 illustrates cross sections of trabecular bone in mammals (B) and dinosaurs (E). Credit: Southern Methodist University

The interdisciplinary team of researchers used engineering failure theories and allometry scaling, which describes how the characteristics of a living creature change with size, to analyze CT scans of the distal femur and proximal tibia of dinosaur fossils.

The team, funded by the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs and the National Geographic Society, is the first to use these tools to better understand the bone structure of extinct species and the first to assess the relationship between bone architecture and movement in dinosaurs. They compared their findings to scans of living animals, such as Asian elephants and extinct mammals such as mammoths.

"Understanding the mechanics of the trabecular architecture of dinosaurs may help us better understand the design of other lightweight and dense structures," said Trevor Aguirre, lead author of the paper and a recent mechanical engineering Ph.D. graduate of Colorado State University.

-

Hadrosaur bones used in the study were extracted from the banks of the Colville River in Alaska’s Prince Creek Formation, about 250 miles north of the Arctic Circle. Credit: Southern Methodist University

-

The structure of the trabecular, or spongy bone that forms in the interior of bones, is unique within dinosaurs, according to a recent study by SMU paleontologists and others. Credit: Southern Methodist University

The idea for the study began ten years ago, when Seth Donahue, now a University of Massachusetts biomedical engineer and expert on animal bone structure, was invited to attend an Alaskan academic conference hosted by Fiorillo and other colleagues interested in understanding dinosaurian life in the ancient Arctic. That's where Fiorillo first learned of Donahue's use of CT scans and engineering theories to analyze the bone structure of modern animals.

"In science we rarely have lightning bolt or 'aha' moments," Fiorillo says. "Instead we have, 'huh?' moments that often are not close to what we envisioned, but instead create questions of their own."

Applying engineering theories to analyze dinosaur fossils and the subsequent new understanding of dinosaurs' unique adaptation to their huge size grew from the 'huh?' moment at that conference.

More information: Trevor G. Aguirre et al, Differing trabecular bone architecture in dinosaurs and mammals contribute to stiffness and limits on bone strain, PLOS ONE (2020). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237042

Journal information: PLoS ONE

Provided by Southern Methodist University