Geometry of intricately fabricated glass makes light trap itself

Laser light traveling through ornately microfabricated glass has been shown to interact with itself to form self-sustaining wave patterns called solitons. The intricate design fabricated in the glass is a type of "photonic topological insulator," a device that could potentially be used to make photonic technologies like lasers and medical imaging more efficient.

Topological materials, which were awarded the Nobel Prize in 2016, have the ability to "protect" the flow of waves through them against unwanted disorder and defects. Until now, our understanding of topological protection of light has been mostly limited to particles of light acting independently, but in a new paper that appears May 22 in the journal Science, researchers at Penn State report that they have used the glass to mediate interaction between photons, directly observing the fundamental wave patterns of these intricate devices.

"People are perhaps more familiar with electronics, but there is a whole parallel world of 'photonics,' where we are concerned with the properties of light instead of electrons," said Mikael Rechtsman, Downsbrough Early Career Development Professor of Physics at Penn State, and senior author of the paper. "There are myriad applications of photonics, including in solar energy, fiber optics for telecommunication, manufacturing using laser cutting, and lidar, which is used, for example, to help control autonomous vehicles. Topological protection offers the promise to make photonic devices more energy efficient, lighter, and more compact."

The concept of topological protection can be applied in electronic, photonic, atomic and mechanical systems. In electronics, for example, topological protection can improve efficiency by getting electrons to flow reliably through a material without scattering. For electrons this protection requires extremely cold temperatures, nearing absolute zero, and very often, a strong external magnetic field, but with photons, all of the experiments can be performed at room temperature, and because photons do not have a charge, without a magnetic field.

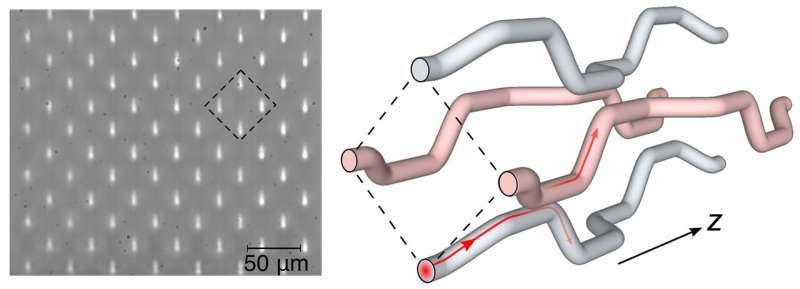

To perform their experiments, the researchers shine a laser through a piece of glass that has a series of extremely precise tunnels carved through it, each with a diameter of about one-tenth that of a human hair. The tunnels, called "waveguides," act like wires, concentrating the flow of light through them. The waveguides in the piece of glass are arranged in a grid, forming an array, but the path of each waveguide through the glass is not straight—it is perhaps better described as serpentine, with twists and turns designed by the researchers with a geometry that leads to the topological protection of light.

"We had to build the fabrication facility in our lab to precisely carve the three-dimensional waveguides through the glass, a process called femtosecond laser writing," said Sebabrata Mukherjee, a postdoctoral researcher at Penn State and first author of the paper. "The ability to write three-dimensional waveguides is crucial to making the device topological, a property that is confirmed experimentally by observing the 'protected' one-way flow of light along the edge of the device."

Through a process called the "Kerr effect," the properties of the glass are changed due to the presence of the intense laser light. This change in the glass mediates an interaction between the many photons, which usually do not interact, propagating through the array. As the power was increased, the light collapsed into a beam that didn't spread out (i.e., diffract), but rather rotated in spirals. The spiral rotation of the solitons is a signature of the specific shape of the waveguides designed by the researchers and an indicator that the device is, indeed, topological.

"Under normal circumstances, photons are oblivious to one another," said Rechtsman. "You can cross two laser beams and neither will be changed by the other. In our system, we were able to get photons to interact and form solitons because the intensity of the laser altered the properties of the glass. The photons became 'aware' of each other through the change in their environment."

Solitons are known to be the most fundamental waveforms in many systems where interaction is mediated by the surrounding environment.

"Theoretically understanding and experimentally probing solitons in topological systems like our waveguide arrays will be a key ingredient in applying topological protection for practical use in photonic devices, especially those that require high optical power," said Rechtsman.

More information: Sebabrata Mukherjee et al. Observation of Floquet solitons in a topological bandgap, Science (2020). DOI: 10.1126/science.aba8725

Journal information: Science

Provided by Pennsylvania State University