NASA astronaut and Expedition 63 Commander Chris Cassidy works in the Combustion Integrated Rack, connecting water umbilicals and checking for leaks in the research device that enables safe fuel, flame and soot studies in microgravity. Credit: NASA

Astronauts donned gloves on the International Space Station to kick off two European experiments on metals and foams, while preparing spacesuits for future work outside their home in space.

The new crew, NASA's Chris Cassidy and Roscosmos' Anatoly Ivanishin and Ivan Vagner, has completed three full weeks of their 195-day mission. They have more space for themselves than the typical crew of six, but not much time to spare.

New metallurgy

Most metals used today are mixtures—alloys—of different metals, combining properties to make new materials. Alloys are everywhere now, from your smartphone to aircraft.

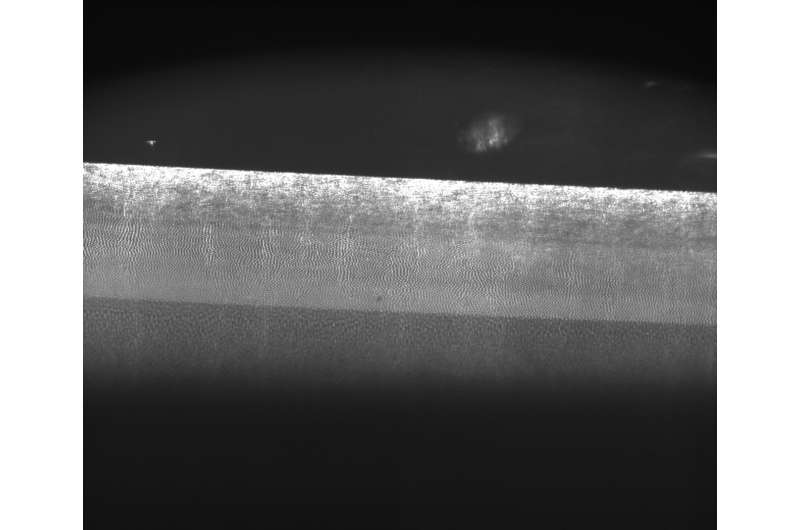

Scientists want to improve their understanding of melting-solidification processes in alloys, and they are taking organic compounds to the Space Station as analogues to experiment with. Microgravity allowed the Transparent Alloys experiment to observe their formation unaffected by convection at microscopic resolution.

Before the new crew arrived, former inhabitant Andrew Morgan handled the samples using the European Microgravity Science Glovebox, a device that allows them to carry out experiments in a sealed and controlled environment, isolated from the rest of the International Space Station.

The behavior of foams was also in the spotlight. The Foam-Coarsening experiment started the science campaign to better understand how bubbles evolve in microgravity. In space, foams are quite stable because there is no drainage in weightlessness. This allows scientists to study the slower phenomena of a bubble becoming bigger and bursting.

This image shows how a metal alloy could look like as it solidifies, using a transparent organic mixture as a stand-in for metals. X-rays allow us to peer into the casting process but ideally researchers should look at the process under normal lighting. Unfortunately, metals are not transparent. Credit: E-USOC

Three sample cells filled with liquid were stored inside the Fluid Science Laboratory in the European Columbus module. After some shaking by pistons inside the cells, laser optics and high-resolution cameras could record the birth evolution of the foam.

The results from this research will not just apply to the foam in your morning cappuccino. Foams are used in a wide range of areas from food to cleaning and sealing products, and even construction.

Bones and muscles

On average astronauts in space lose 1% bone density a month due to living in weightlessness. Studying what happens during long stays in space offers a good insight into osteoporosis.

Cosmonauts Anatoly Ivanishin and Ivan Vagner ran their first sessions of European experiment EDOS-2 to help scientists understand the effects of spaceflight on bone, and how it recovers after returning to Earth.

-

A sample cell unit of the Foam Coarsening experiment on the International Space Station. By shaking the pistons inside the cell, foam is generated. Credit: NASA

-

Flight engineer and European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti exercises on the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED) in the Tranquility Node 3 during her Futura mission in 2014-2015. Credit: ESA/NASA

-

This gadget looks like a precursor to the devices medical officers use to scan patients in science fiction, and it is not far off. The MyotonPRO tests muscle tension and stiffness. Credit: Cadmos

A better understanding of bone loss and its recovery is crucial not only for astronauts, but also for patients suffering from bone diseases or fractures during aging and immobilization on our planet.

NASA astronaut Chris Cassidy performed his first in-space session of the Myotones experiment that monitors his muscle tone, stiffness and elasticity. A non-invasive device measured his back, shoulders, arms and legs—areas known to be affected by atrophy during extended inactivity periods.

Results will be compared with measurements before and after his spaceflight. Chris is one 12 astronauts to take part in this experiment that could improve the lives of many people affected by strained muscles with new strategies for rehabilitation treatments.

Provided by European Space Agency