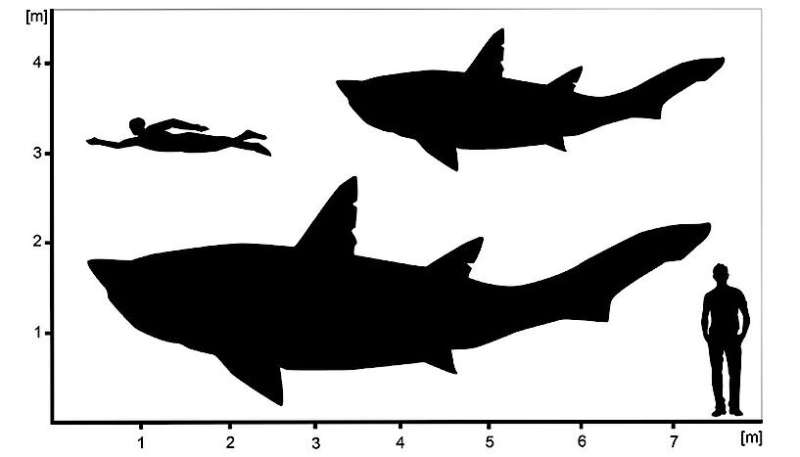

Hypothetical outlines of †Ptychodus showing the minimum and maximum size estimations for the sub-adult specimen from Spain. Credit: Patrick L. Jambura

Scientists of the University of Vienna have examined parts of a vertebral column found in northern Spain in 1996, and assigned it to the extinct shark group Ptychodontidae. In contrast to teeth, shark vertebrae bear biological information like body size, growth and age, which allowed the team of Patrick L. Jambura to gain new insights into the biology of this mysterious shark group.

In 1996, palaeontologists found skeletal remains of a giant shark on the northern coast of Spain, near the city Santander. Here, the coast comprises meter-high limestone walls that were deposited during the Cretaceous period around 85 million years ago, when dinosaurs still roamed the world. Scientists from the University of Vienna examined this material now and were able to assign the remains to the extinct shark family Ptychodontidae, a group that was specious and successful in the Cretaceous but vanished mysteriously before the infamous end-Cretaceous extinction event.

Shark vertebrae are rare but precious in the fossil record

Ptychodontid sharks are mainly known from their flattened teeth, which allowed them to crush hard-shelled prey like bivalves or ammonites, similar to some of today's ray species. However, the find in Spain consists only of parts of the vertebral column and placoid scales (teeth-like scales), which are much rarer than teeth in the fossil record.

In contrast to teeth, shark vertebrae bear important information about a species' life history such as size, growth and age, which are saved as growth rings inside the vertebra, like in the stem of trees. Statistical methods and the comparison with extant species allowed the scientists to decode these data and reconstruct the ecology of this enigmatic shark group.

Ptychodontid sharks grew big and old

"Based on the model, we calculated a size of 4-7 meters and an age of 30 years for the examined shark. It's astonishing that this shark was not yet mature when it died despite its rather old age," says Patrick L. Jambura, lead author of the study. Sharks follow an asymptotic growth curve, meaning that they grow constantly until maturation, and after that, the growth curve flattens, resulting from a reduced growth rate. "However, this shark doesn't show any signs of flattenings or inflections in the growth profile, meaning that it was not mature—a teenager, if you want. This suggests that these sharks even grew much larger and older."

The study suggests that ptychodontid sharks grew very slow, matured late, but also showed high longevity and reached enormous body sizes. "This might have been a main contributor to their success, but also, eventually, demise."

Do modern sharks face a similar fate?

Many living sharks, like the whale shark or the great white shark, show very similar life history traits, a combination of low recruitment and late maturation, which makes them vulnerable to anthropogenic threats, like overfishing and pollution.

"It might be the case that similar to today's sharks, ptychodontid sharks faced changes in their environment to which they could not adapt quickly enough, and ultimately led to their demise, even before dinosaurs went extinct. However, unlike in the Cretaceous period, it is up to us now to prevent this from happening to modern sharks again and to save the last survivors of this ancient and charismatic group of fishes."

More information: Patrick L. Jambura et al. Articulated remains of the extinct shark Ptychodus (Elasmobranchii, Ptychodontidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Spain provide insights into gigantism, growth rate and life history of ptychodontid sharks, PLOS ONE (2020). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231544

Journal information: PLoS ONE

Provided by University of Vienna