Future detectors to detect millions of black holes and the evolution of the universe

Gravitational-wave astronomy provides a unique new way to study the expansion history of the Universe. On 17 August 2017, the LIGO and Virgo collaborations first detected gravitational waves from a pair of neutron stairs merging. The gravitational wave signal was accompanied by a range of counterparts identified with electromagnetic telescopes.

This multi-messenger discovery allowed astronomers to directly measure the Hubble constant—a unit of measurement that tells us how fast the Universe is expanding. A recent study by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav) led by researchers Zhiqiang You and Xingjiang Zhu (Monash University), studied an alternative way to do cosmology with gravitational-wave observations.

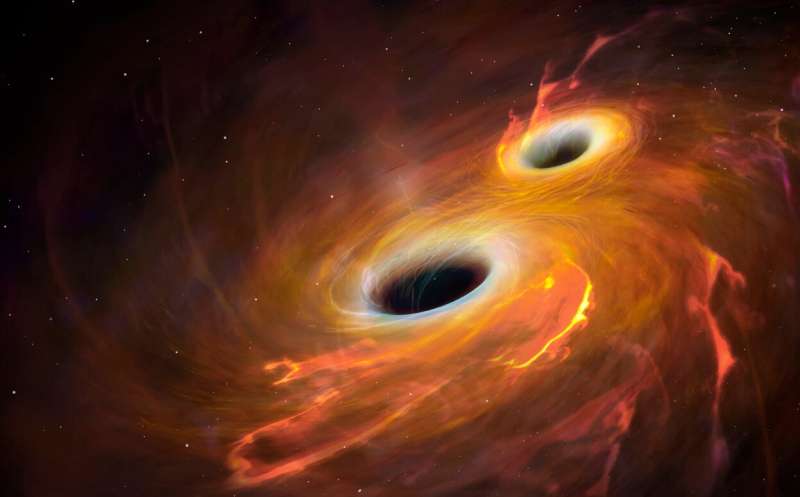

In comparison to neutron star mergers, black hole mergers are much more abundant sources of gravitational waves. Whereas there have been only two neutron star mergers detected so far, LIGO and Virgo collaborations have published 10 binary black hole merger events and dozens more candidates have been reported.

Unfortunately, no electromagnetic emission is expected from black hole mergers. Theoretical modeling of supernovae—powerful and luminous stellar explosions—suggests that there is a gap in the masses of black holes around 45-60 times the mass of our Sun. Some inconclusive evidence that supports this mass gap was found in observations made in the first two observing runs of LIGO and Virgo. The new OzGrav research shows that this unique feature in the black hole mass spectrum can help determine the expansion history of our Universe using gravitational-wave data alone.

OzGrav Ph.D. student and first author Zhiqiang You says: "Our work studied the prospect with third-generation gravitational-wave detectors, which will allow us to see every binary black hole merger in the Universe."

Apart from the Hubble constant, there are other factors that can affect how black hole masses are distributed. For example, scientists are still uncertain about the exact location of the black hole mass gap and how the number of black hole mergers evolves over the cosmic history.

The new study demonstrates that it is possible to simultaneously measure black hole masses along with the Hubble constant. It was found that a third-generation detector like the Einstein Telescope or the Cosmic Explorer should measure the Hubble constant to better than one percent within one-year's operation. Moreover, with merely one-week observation, the study revealed it is possible to distinguish the standard dark energy-dark matter cosmology with its simple alternatives.

More information: Zhi-Qiang You, et al. Standard-siren cosmology using gravitational waves from binary black holes, arxiv.org/abs/2004.00036. arXiv:2004.00036v1 [astro-ph.CO]