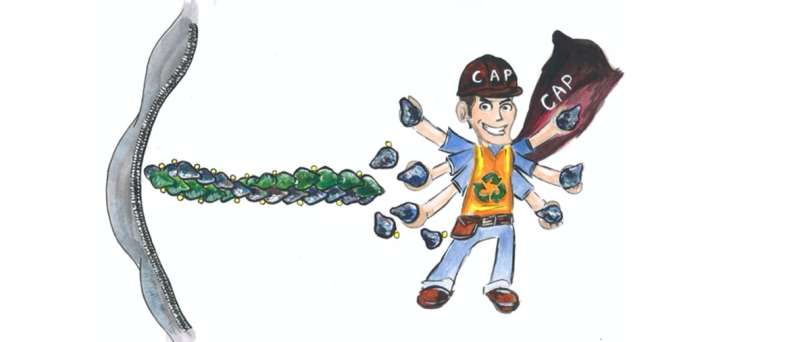

Cyclase-associated protein (CAP) promotes the rapid depolymerisation of actin filaments and recycles the resulting actin monomers for a new round of filament assembly. Credit: Reena Kumari

Researchers have found that two specific proteins take apart actin filaments at one end and return the building blocks to the other end for a new round of polymerization. The structure of this machinery driving cell motility may open new opportunities for developing therapeutics to inhibit cell migration in cancer.

Many cells in our body constantly change their shape and move within our tissues. For example, wound healing and the immune system depend on migrating cells. On the other hand, uncontrolled cell migration is a hallmark of metastasis during the development of malignant cancers, so cell migration must be very tightly regulated.

The driving force for cell migration is produced by a protein called actin. Actin monomers act as building blocks by polymerizing into rod-like filaments that push the leading edge of the cell forward. The polymerization of the actin filaments must be balanced by depolymerization of the filaments at the other end.

Now, scientists at the University of Helsinki, Finland, and Institut Jacques Monod, France, have identified a molecular machinery which drives rapid depolymerization of actin filaments and recycles the resulting actin monomers for a new round of polymerization. Two proteins, cyclase-associated protein and cofilin, work together in this.

"By using X-ray crystallography and computer simulations, we could actually see the atomic details of how these two proteins embrace actin filaments and disassemble them into their building blocks. One of the most exciting parts of the project was to see under the microscope how actin filaments suddenly began disappearing when we introduced these two proteins into their vicinity," says Ph.D. student Tommi Kotila, the lead author of the study from HiLIFE Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, .

In malignant tumors, cells go haywire in their movements, because their migration machinery is not properly controlled. Because, in cancer cells, the regulation of cyclase-associated protein is often defective, the atomistic structure of this machinery may open new avenues for developing therapeutics to inhibit cell migration in cancer.

"This is a great contribution to our understanding of the basic principles of cell migration. It also helps us understand the molecular basis of the uncontrolled migration of cancer cells," says academy professor Pekka Lappalainen from the Institute of Biotechnology.

More information: Tommi Kotila et al. Mechanism of synergistic actin filament pointed end depolymerization by cyclase-associated protein and cofilin, Nature Communications (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-13213-2

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by University of Helsinki