Credit: National Research University Higher School of Economics

Researchers from HSE University have shown that the 2010 happiness level of citizens from Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and other Arab countries could provide a much more accurate forecast of the Arab Spring events than purely economic indices, such as GDP per capita and unemployment rate.

Motifs for action

At the beginning of the 2010s, a new wave of political protests swept through North Africa and the Middle East. The disturbances broke out in Tunisia in December 2010, resulting in the president dismissing the government and fleeing the country on January 15, 2011. Two days before, on January 13, political protests began in Libya, leading to the overthrow of Gaddafi's regime, followed by a military intervention and a civil war. At that time, unrests and riots started in Syria, Egypt, and Yemen, and by the end of February, as many as 19 nations had been involved in the event of the Arab Spring.

The Arab Spring is not the first example of the 'revolution wave' in human history. In the middle of the 19th century, a similar series of political upheavals happened in Europe (the Spring of Nations). This leads to the conclusion that the society seeking a wide confrontation with the existing authorities possesses particular characteristics which can be identified by demographic, sociological, economical, or any other type of monitoring.

In the 1960s, street rallies may have been driven by relative deprivation—that is, moral dissatisfaction of the people who feel they lack resources they believe they deserve. For example, this deprivation may be caused if the elected authorities fail to keep their promises, while citizens aspire to the quality of life comparable with that of other nations.

According to HSE Professor Andrey Korotayev, relative deprivation is a psychological term denoting the subjective feeling of a gap between expected and actual welfare. Relative deprivation should not be confused with absolute deprivation, as the latter means real lack of immediate basic resources, such as shelter, food, etc., i.e., it is an economic rather than psychological metric.

The theory of relative deprivation—without quantitative assessments—has been widely used to analyze political processes in many countries, including Russia. However, there is no common opinion on the role of relative deprivation in generating social and political events, as it is still quite unclear how to measure it accurately.

Sociologists propose a 10-point scale to measure Subjective Feeling of Happiness (SFH). According to Veenhoven, a typical happy person is a citizen of an economically successful state that guarantees stable democracy and freedom; a representative of the dominant majority, occupying the top positions on the social ladder; and a supporter of moderately conservative views.

Arab Spring Reasons

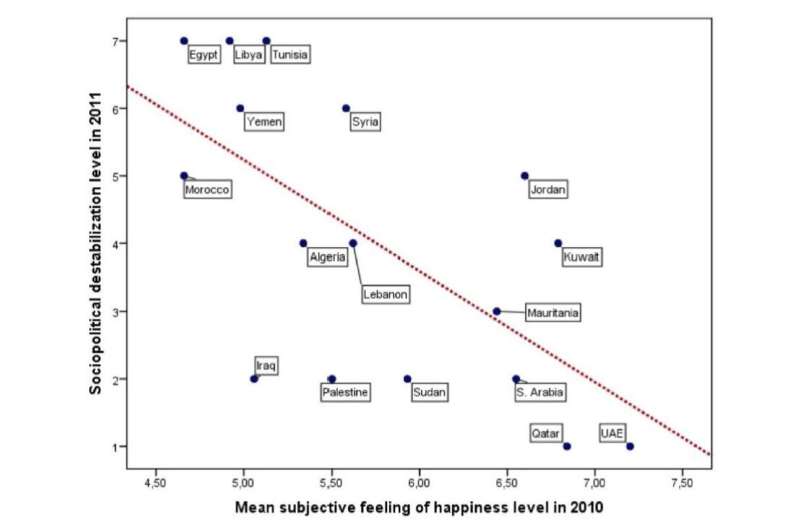

Russian sociologists Andrey Korotayev and Alisa Shishkina sought to verify subjective happiness efficiency as a relative deprivation metric based on the Arab Spring countries data. They ranked the countries according to the sociopolitical destabilization index. The index can be evaluated in points—from 1 to 7—depending on the scale and consequences of the protests in the country. The sociopolitical destabilization index equals 1 in countries with very few low-intensity separate protests, such as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, while 7 is given to nations that experienced revolutions (Egypt, Libya, Tunisia).

Having compared the index with the 2010 SFH values, the researchers found that in the countries with a low-intensity protest activity people were subjectively happier than inhabitants of the states where demonstrations and riots lasted for quite a while. These people were also happier than citizens of countries with a higher GDP per capita. For example, the highest SFH level (7.2) was recorded in the United Arab Emirates, with its 2010 GDP per capita exceeding $57,000; while Morocco appeared to have the lowest SFH level (4.66) and GDP per capita of $6,000.

In addition, the researchers analyzed correlation between GDP on the eve of the Arab Spring and the sociopolitical destabilization index. The findings prove that the average protest activity was much lower in affluent Arab countries than in their poor neighbours.

Jobs, money, and something else

On the face of it, the findings seem to suggest that revolutionary sentiments are driven by economic factors, not socio-psychological reasons. However, subsequent multiple regression analyses—applying the sociopolitical destabilization index, the change in the level of the subjective feeling of happiness between 2009 and 2010, GDP per capita and unemployment rate—clearly show that more weight should be placed on socio-psychological rather than purely economic explanation of the genesis of the Arab revolutions.

Meanwhile, the researchers point out that the subjective feeling of happiness cannot be seen as the ultimate predictor of protests. We should remember that a number of political, social, demographic, historical, religious, and economic factors played their role in sociopolitical destabilization. Relative deprivation appears to be one of many possible reasons.

Andrey Korotayev says that the researchers are planning to apply a similar approach to analyze political processes in other countries across the globe. By doing so, they will try to measure the threshold level of relative deprivation that forces people to take part in protests, including peaceful demonstrations, mass strikes, or terrorist acts.

More information: Andrey V. Korotayev et al, Relative Deprivation as a Factor of Sociopolitical Destabilization: Toward a Quantitative Comparative Analysis of the Arab Spring Events, Cross-Cultural Research (2019). DOI: 10.1177/1069397119882364

Provided by National Research University Higher School of Economics