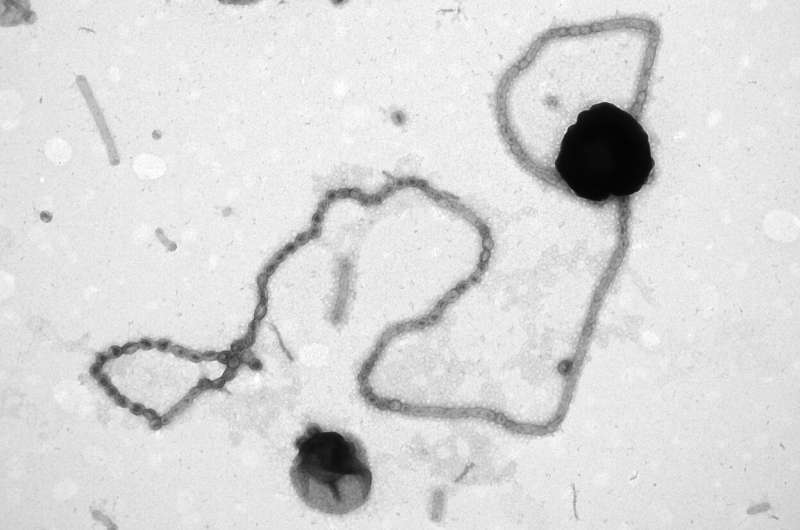

Electron microscope image of a long pearl chain on a flavobacterium. Credit: Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology / Tanja Fischer

For the first time, scientists in Bremen were able to observe bacteria forming pearl chains that protrude from the cell surface. These pearl chains serve to better absorb and store substances from the environment. The researchers now present their results in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

Bacteria eat by absorbing substances from their environment through the cell wall. However, there are natural physical limits to this way of eating. To bypass these limits, some bacteria enlarge their cell surface. For example, they form tubular extensions or small bubbles, so-called vesicles. A group of researchers led by Jens Harder from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany, has now observed for the first time that bacteria initially form tubes and then vesicles.

North Sea bacteria with pearl chains

"We have investigated a flavobacterium that is widespread in the North Sea," says Harder. These bacteria live in a nutrient-poor, so-called oligotrophic, environment. It is therefore advantageous for them to enlarge their cell surface and thus have more space to hold and absorb sugar and other food with enzymes on the surface. "Bacteria that have vesicles or tubes for this purpose have already been observed," Harder continues. "The flavobacteria we studied have one after the other: First we observed tubes, then regular strings of pearls. The formation of pearls probably results from a twisting of the fatty acid molecules in the cell wall."

Ecologically successful strategy

The flavobacteria examined in this study appear in large numbers in so-called bacterial blooms in the North Sea, which occur after the annual algae spring blooms. They have a special set of enzymes to use laminarin, the storage sugar of the algae. Harder and his colleagues fed the bacteria colored laminarin to check whether there was an exchange between the pearl chains and the "main cell." And indeed, the dye also appeared in the pearl chains. "We think that enzymes on the surface of the pearl chains capture, hold and break up the laminarin sugar and then deliver it to the cell," Harder explains. It seems to pay off: "The mass occurrence of flavobacteria after algal blooms clearly reveals their ecological success."

More information: Tanja Fischer et al, Biopearling of Interconnected Outer Membrane Vesicle Chains by a Marine Flavobacterium, Applied and Environmental Microbiology (2019). DOI: 10.1128/AEM.00829-19

Journal information: Applied and Environmental Microbiology

Provided by Max Planck Society