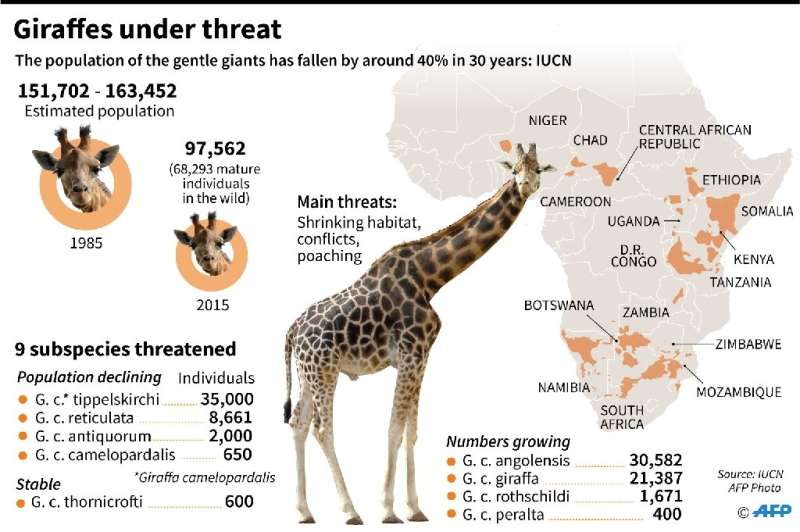

Giraffe numbers across the continent fell 40 percent between 1985 and 2015, to just under 100,000 animals

For most of his life as a Samburu warrior, Lesaiton Lengoloni thought nothing of hunting giraffes, the graceful giants so common a feature of the Kenyan plains where he roamed.

"There was no particular pride in killing a giraffe, not like a lion... (But) a single giraffe could feed the village for more than a week," the community elder told AFP, leaning on a walking stick and gazing out to the broad plateau of Laikipia.

But fewer amble across his path these days: in Kenya, as across Africa, populations of the world's tallest mammals are quietly, yet sharply, in decline.

Giraffe numbers across the continent fell 40 percent between 1985 and 2015, to just under 100,000 animals, according to the best figures available to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

But unlike the clarion calls sounded over the catastrophic collapse of elephant, lion and rhino populations, less attention was paid to the giraffe's private crisis.

"The giraffe is a big animal, and you can see it pretty easily in parks and reserves. This may have created a false impression that the species was doing well," said Julian Fennessy, co-chair of the IUCN's specialist group for giraffes and okapis.

The rate of decline is much higher in central and eastern regions, with poaching, habitat destruction and conflict the main drivers blamed for thinning herds of these gentle creatures.

In Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia, reticulated giraffe numbers fell 60 percent in the roughly three decades to 2018, the IUCN says.

The Nubian giraffe meanwhile has suffered a tragic decline of 97 percent, pushing this rarer variety toward total extinction.

Giraffes under threat

Further afield in Central Africa, the Kordofan giraffe, another of the multitude subspecies, has witnessed an 85 percent decrease.

In 2010, giraffes were a species of "least concern" on the IUCN red list. But six years later they leapt to "vulnerable", one step down from critical, catching many by surprise.

"This is why for the giraffe we speak of the threat of a silent extinction," said Jenna Stacy-Dawes, research coordinator at the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research.

Mysterious giants

Despite this, an international effort underway to put giraffes squarely on the global conservation agenda has divided professional opinion.

Six African nations are pushing to regulate the international trade in giraffes under the UN Convention on Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which meets from August 17 to 28 in Geneva.

Those advocating for the change, including Kenya, want the giraffe classified as "a species that, although not necessarily currently threatened with extinction, could become so if trade in their specimens were not closely controlled".

Critics however say there is little evidence the international wildlife trade is responsible for dwindling giraffe numbers. A lack of reliable data has long hindered efforts to protect them.

"Compared to other charismatic species like elephants, lions and rhinos, we know very little about giraffes," said Symon Masiaine, a coordinator in the Twiga Walinzi giraffe study and protection program, which began in Kenya in 2016.

In Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia, reticulated giraffe numbers fell 60 percent in the roughly three decades to 2018

"Nowadays, we are still far behind, but we are making progress."

Almost nothing is reliably known about giraffe populations in Somalia, South Sudan and eastern parts of Democratic Republic of Congo, where collecting such information is perilously difficult.

But even research outside conflict zones has been patchy.

Arthur Muneza, from the Giraffe Preservation Foundation, said the first long-term study of giraffes was not carried out until 2004. Data on giraffes is often gathered as an afterthought by researchers focussing on other wildlife, he added.

"Without reliable data, it is more difficult to take appropriate conservation measures," Muneza said.

It was not until 2018 that the IUCN had enough statistics to be able to differentiate the threat levels facing many giraffe subspecies.

The reticulated and Masai giraffes, for examples, were classified as "endangered" while the Nubian and Kordofan were "critically endangered".

Trophy hunting

Under the proposal before CITES, the legal trade in giraffe parts, including those obtained by trophy hunters on Africa's legal game reserves, would be globally regulated.

Six African nations are pushing to regulate the international trade in giraffes under the UN Convention on Trade in Endangered Species

Member countries would be required to record the export of giraffe parts or artefacts, something only the United States currently does, and permits would be required for their trade.

But observers say the limited information available suggests most of this trade originates from places where giraffe numbers are actually rebounding, like South Africa and Namibia, where game hunting is legal.

Muneza says there isn't a clear enough picture that the legal trade is linked to declining giraffe numbers.

"The first step should be to conduct a study to find out the extent of international trade and its influence on giraffe populations," he said.

Those supporting the proposal before Geneva talk of a "precautionary principle"—doing something now before it is too late.

For Masiaine, the Kenyan giraffe researcher, any publicity is good publicity for these poorly-understood long-necked herbivores.

"It means that people are talking about the giraffe," he said. "And the species really needs that."

Conservationist Symon Masiaine (driving), who study and carry out awareness on giraffe plight and conservation, and a colleague scope for giraffe clusters at Loisaba conservancy in Laikipia on August 5, 2019. In Kenya, as across the wider African continent, the world's tallest mammals are less abundant than they once were, their numbers having quietly yet steadily declined in recent decades.The twin drivers of poaching and habitat destruction have sent populations of this gentle and charismatic creature into freefall.

Factfile on Africa's under-studied giant: the giraffe

One of the most under-studied large mammals in Africa, the giraffe may be on a slow path to extinction, with numbers dropping 40 percent in the three decades to 2015.

Here are unusual facts about one of the world's most distinctive-looking creatures.

Neck

The giraffe's best-known feature can be longer than most people are tall. However, like humans, its neck still only has seven vertebrae. Each is about 25 centimetres (10 inches) long.

It is used to reach high up into trees for food but too short to reach the ground, so the animals have to splay their legs or kneel down to drink water. Luckily they only drink every few days and get most of their hydration from plants.

The neck is also used in an elaborate ritual fight known as "necking" in which giraffes swing at each other to establish dominance.

Markings

With its spotted pattern and long legs and neck, the giraffe was given the Latin name "camelopardalis", meaning "camel marked like a leopard".

But the spots are not only for camouflage.

According to the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF), each patch is surrounded by a sophisticated system of blood vessels which act as thermal windows to release body heat.

A thermal scan of a giraffe shows the intensity of heat in its body matching the pattern of the spots.

Like the human fingerprint, each giraffe has its own unique pattern.

Big tongue, big heart

It's not just the neck and legs which are outsized on a giraffe, which despite its iconic status is not one of Africa's "Big Five" wildlife.

Its tongue can measure up to 50 cm to give the animal even more leverage in nibbling from the top of its favoured tree, the acacia.

The tongue's blue-black colour is believed to shield the organ from sun exposure and it is widely accepted that a giraffe's sticky saliva has antiseptic properties to protect it from spiky thorns on the acacia.

A giraffe's heart weights up to 11 kilogrammes (24 pounds)—to power blood up a neck of nearly two metres (six and a half feet)—and beats up to 170 times per minute, double the speed of a human heart.

The blood vessels inside giraffe legs have been studied by NASA engineers trying to improve spacesuit design.

Breeding

Giraffes have one of the longest gestation periods, at 15 months. They give birth standing up, which means their calves drop just under two metres to the ground.

This startling introduction to life gets them up and running around in less than an hour. A newborn calf is bigger than the average adult.

In the wild, giraffes can live up to 25 years, while in captivity they can survive over 35 years.

Genetics

Giraffes evolved from an antelope-like animal of about three metres tall that roamed the forests of Asia and Europe 30 to 50 million years ago. Its closest living relative is the okapi.

In September 2016 scientists revealed there were in fact four distinct giraffe species and not one divided into nine subspecies, as initially thought. Discussions are underway to have this recognised by the IUCN, so specific initiatives can be tailored for each subspecies.

© 2019 AFP