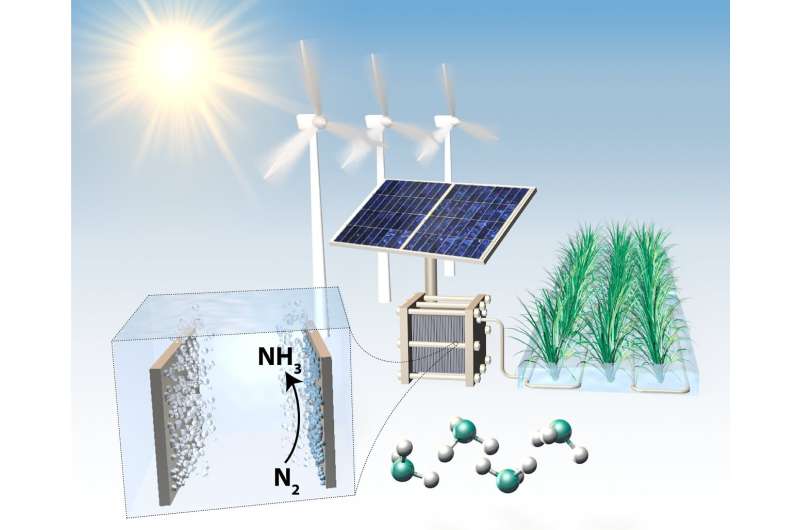

Electrochemically produced ammonia. Credit: Jakob Kibsgaard

Ammonia (NH3) is one of the most widely produced chemicals, with a global output of 170 megatons per year. It is the key ingredient in the production of fertilizers, and thus plays a critical role in sustaining the world's population. However, more than 1 percent of global energy is consumed by the production of ammonia, which involves the reaction of dinitrogen (N2) from air and dihydrogen (H2), via the Haber-Bosch process.

Although industry has seen some breakthroughs in terms of efficiency, the hydrogen atoms in ammonia are derived from the fossil fuel methane (CH4), and carbon dioxide (CO2) is produced as a byproduct. In other words, the Haber Bosch process is unsustainable. Moreover, it requires high temperatures and pressures, meaning that it can only be produced in large centralised reactors, far from the point-of-consumption. Consequently, the logistical and safety challenges of transporting ammonia, which is both toxic and corrosive, prevent many potential users from being able to use it, particularly in developing countries.

For many years, scientists have therefore been working hard to find an alternative, electrochemical method of synthesising ammonia, which could be powered by renewable energy and produced on a localised basis, at the point of use. There are major challenges to be solved—scientific as well as technical—before the process can become scalable and profitable.

Experimental studies—thus far—have been unable to match the efficiency of the dominant Haber-Bosch process. Moreover, many of these studies fail to rule out contamination due to the ammonia or other nitrogen-containing compounds already present in air, human breath, ion-conducting membranes or even the catalyst itself.

A new study in Nature by an international team of scientists from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), Stanford University and Imperial College London highlights this issue.

"Synthesis of ammonia through electrochemical processes is gathering enormous interest, not only from academic researchers but also from industry and government. This interest is driven by the need to make the production of ammonia less dependent on fossil fuels. However, many academic groups fail to prove that the ammonia is indeed derived from the N2 molecule. This is in part because of the very small amounts of ammonia produced which makes even small contaminations yield a false positive," says Associate Professor Jakob Kibsgaard at DTU.

The protocol put forth by the scientists uses nitrogen-15 (15N2), an isotope that allows them to detect and quantify the electroreduction of N2 to ammonia. Through this method, they are able to separate the effects of spurious contamination from true N2 reduction.

"If electrochemical processes become more efficient, isotope labelling will become less of an issue, as we will be producing larger amounts of ammonia. Even so, we have studies coming out at the moment that fail to adhere to even the most basic protocols to ensure that the results are valid," says Senior Lecturer Ifan E. L. Stephens at Imperial College London.

Using their protocol, the scientists have proven that a method reported in 1993 by another team of scientists (from Tokyo Institute of Technology), unequivocally yields ammonia derived from N2. While many studies need to be re-evaluated, the current result is significant, as it shows that the electrochemical production of ammonia is indeed feasible.

"We hope this paper will remind the research community to use the proper control experiments and protocols to correctly evaluate their research. We are all part of an emerging field that could have a very positive impact on ammonia production and global CO2 emissions. Consequently, we need to be sure that we make good use of our time in the lab—and this research could help us to do so." says Professor Ib Chorkendorff at DTU.

More information: Nature (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1260-x

Journal information: Nature

Provided by Technical University of Denmark