Newly discovered fossil footprints force paleontologists to rethink ancient desert inhabitants

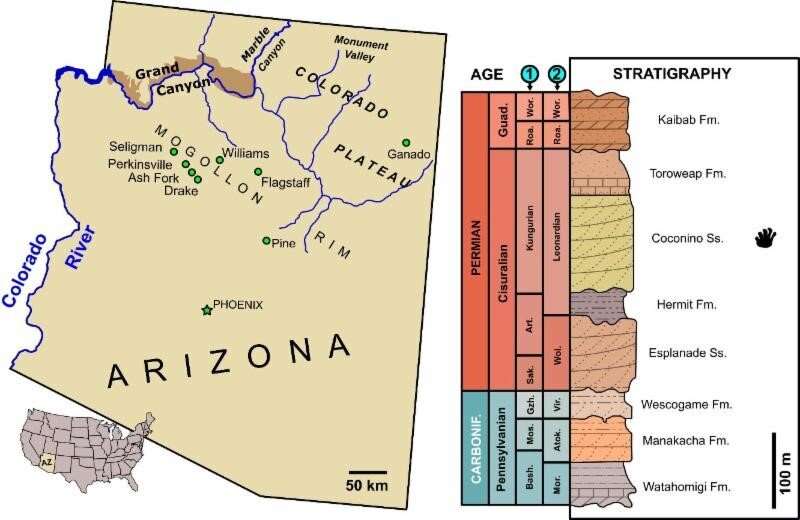

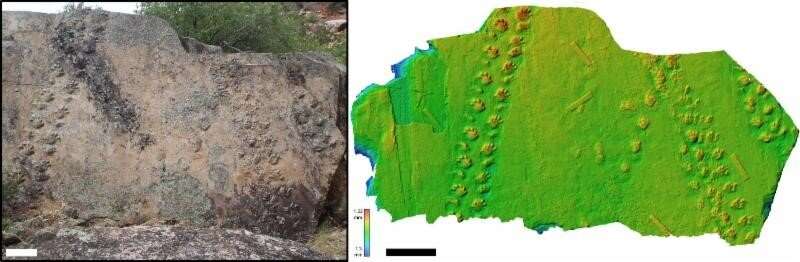

An international team of paleontologists has united to study important fossil footprints recently discovered in a remote location within Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. A large sandstone boulder contains several exceptionally well-preserved trackways of primitive tetrapods (four-footed animals) which inhabited an ancient desert environment. The 280-million-year-old fossil tracks date to almost the beginning of the Permian Period, prior to the appearance of the earliest dinosaurs.

The first scientific article reporting fossil tracks from the Grand Canyon was published in 1918, just a year before the park was established as a unit of the National Park Service. One hundred years later, during the Centennial Celebration for Grand Canyon National Park, new research on ancient footprints from the park is being presented in a scientific publication released this week. Brazilian paleontologist Dr. Heitor Francischini, from the Laboratory of Vertebrate Paleontology,Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, is the lead author of the new publication, working with scientists from Germany and the United States.

Francischini and Dr. Spencer Lucas, Curator of Paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science in Albuquerque, New Mexico, first visited the Grand Canyon fossil track locality in 2017. The paleontologists immediately recognized the fossil tracks were produced by a long-extinct relative of very early reptiles and were similar to tracks known from Europe referred to as Ichniotherium (ICK-nee-oh-thay-ree-um). This new discovery at Grand Canyon is the first occurrence of Ichniotherium from the Coconino Sandstone and from a desert environment. In addition, these tracks represent the geologically youngest record of this fossil track type from anywhere in the world.

Ichniotherium is a kind of footprint believed to have been made by an enigmatic group of extinct tetrapods known as the diadectomorphs. The diadectomorphs were a primitive group of tetrapods that possessed characteristics of both amphibians and reptiles. The evolutionary relationships and paleobiology of diadectomorphs have long been important and unresolved questions in the science of vertebrate paleontology.

Although the actual track maker for the Grand Canyon footprints may never be known for certain, the Grand Canyon trackways preserve the travel of a very early terrestrial vertebrate. The measurable characteristics of the tracks and trackways indicate a primitive animal with short legs and a massive body. The creature walked on all four legs and each foot possessed five clawless digits.

Another interesting aspect of the new Grand Canyon fossil tracks is the geologic formation in which they are preserved. The Coconino Sandstone is an eolian (wind-deposited) rock formation that exhibits cross-bedding and other sedimentary features indicating a desert / dune environment of deposition. Therefore, the presence of Ichniotherium in the Coconino Sandstone is the earliest evidence of diadectomorphs occupying an arid desert environment.

According to Francischini, "These new fossil tracks discovered in Grand Canyon National Park provide important information about the paleobiology of the diadectomorphs. The diadectomorphs were not expected to live in an arid desert environment, because they supposedly did not have the classic adaptations for being completely independent of water. The group of animals that have such adaptations is named Amniota (extant reptiles, birds and mammals) and diadectomorphs are not one of them."

Lucas also notes that "paleontologists have long thought that only amniotes could live in the dray and harsh Permian deserts. This discovery shows that tetrapods other than reptiles were living in those deserts, and, surprisingly, were already adapted to life in an environment of limited water."

Provided by New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science