Scientist drawing collected by Julie Libarkin. Credit: Scott E. Kalafatis and Julie C. Libarkin, Geosphere.

Creating new policies that deal with important issues like climate change requires input from geoscientists. Policy makers, media outlets, and the general public are interested in hearing from experts, and scientists are put under increasing amounts of pressure to effectively engage in policy decisions.

"Over the years, scientists have received a lot of criticism about how they engage in policy discussions," says co-author Scott Kalafatis, assistant professor at Dickinson College. "But I've worked with a lot of scientists who were remarkably dedicated and skilled at engaging in the policy process." Yet, despite these efforts, Kalafatis says it's still unclear how scientists see themselves in those interactions, and some are unsure of how they might best leverage their strengths into policy decisions.

In their new paper for Geosphere, Kalafatis and his co-author Julie Libarkin investigate how scientists in all stages of their career perceive interactions with policy makers. They discovered that there's not a one-size-fits-all approach to interactions between scientists and policy makers—and relying on your strengths can be the most effective way to communicate.

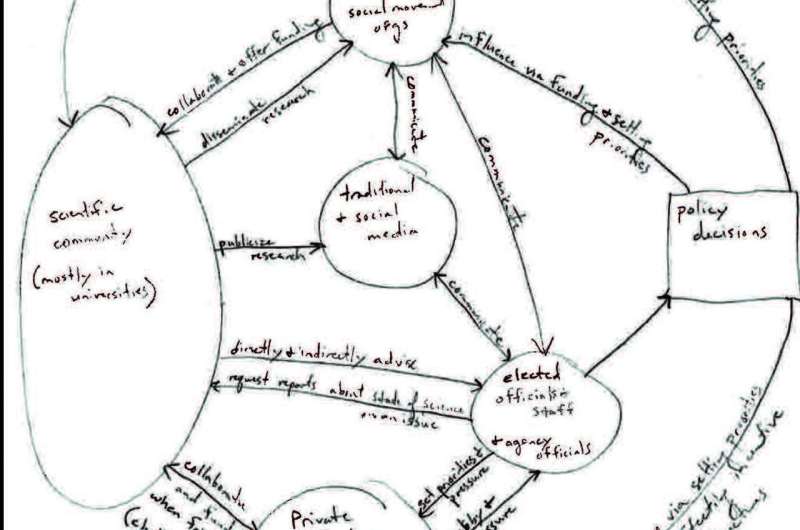

Libarkin, a professor at Michigan State University, developed a way to analyze drawings to help understand the interactions of science and policy. The authors asked a group of 61 geoscientists to draw a picture of how they imagined science migrating through society and leading to policy decision making. Within the drawings, key elements where research was provided or needed for decision making were identified and labeled. The team assigned the key elements in each drawing specific codes for use in their statistical analysis.

Using the codes, they found five different ways scientists viewed their roles in science-policy decisions: a beacon informing decisions, a collaborator working alongside policymakers to co-produce knowledge, an educator enhancing the capacity of society in the classroom and media, an outcast whose efforts to inform are rejected, or an investigator whose research may or may not be used depending on how others interpret it.

The team believes that these scientists' impressions of how science and policy connect with one another depended very much on who they were, where they were in their career, and where they wanted to be in the future. The researchers note that highlighting the five science-policy models is an important initial step to helping scientists tailor their approach. "In my opinion, there's not 'one neat trick' to make scientists engage more effectively with policy," says Kalafatis. Instead, he says the most effective approach is tailored to people's particular personality, career, and experiences.

In particular, understanding how to best train geoscientists for policy interactions could be especially helpful to the next generation of researchers, says Kalafatis. "I find that my undergraduate students have been told their whole lives that the world is under threat from global environmental challenges," he says. "They are hungry to learn practical ways that they might be able to contribute to addressing these challenges in ways both large and small in their professional lives."

More information: Scott E. Kalafatis et al, What perceptions do scientists have about their potential role in connecting science with policy?, Geosphere (2019). DOI: 10.1130/GES02018.1

Journal information: GeoSphere

Provided by Geological Society of America