Wastewater reveals the levels of antibiotic resistance in a region

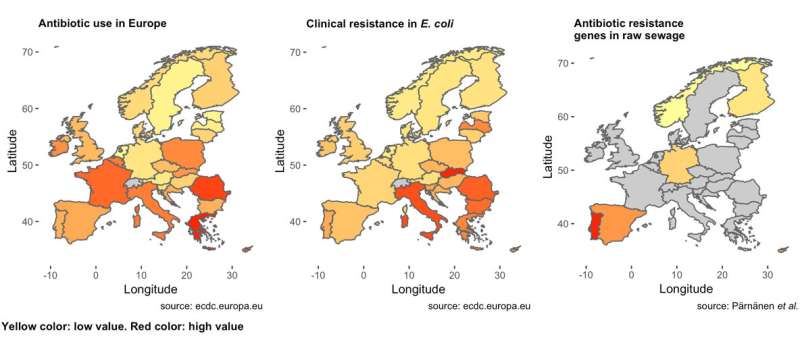

An international study compares the number of antibiotic resistance genes found in the water treatment plants of Finland, Norway, Germany, Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus. The results show that the number of antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater corresponds with the number of such bacteria found in samples collected from patients in that region, as well as with overall antibiotic consumption in the area.

However, modern, well-functioning wastewater treatment plants seem to be quite effective in removing bacteria resistant to antibiotics from the water during the treatment process. Nevertheless, the study did indicate that it's possible for a treatment plant to function as an incubator of antibiotic resistance under certain conditions. Among the 12 plants studied, in one facility, the relative number of antibiotic resistance genes increased during the purification process.

The study was conducted by an international research group. The University of Helsinki was represented in the study by microbiologist Marko Virta's group from the Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry. The results were published in Science Advances.

Southern Europe uses more antibiotics than northern Europe

European antibiotic use varies widely by country. Overall, southern Europeans use many more antibiotics than their counterparts in the north. Similarly, people living in the south of Europe tend to carry a much higher number of antibiotic-resistant bacteria than those living in northern Europe.

Among the countries in the study, antibiotic use is relatively high in Spain, Portugal, Cyprus, and Ireland, whereas in Finland, Norway and Germany antibiotics are prescribed and used less. The amount of antibiotic resistance in these countries mirrors the division above: the Spaniards, the Portuguese, the Cypriots and the Irish have more bacteria resistant to antibiotics in their bowels than do the Finns, the Norwegians and the Germans.

All of the countries investigated in the study had various antibiotic resistance genes in the wastewater entering their treatment plants. The number of resistance genes found in wastewater bound for purification was higher in Portugal, Spain, Cyprus and Ireland than in Finland, Norway and Germany.

However, the treatment plants were successful in eliminating resistance from most of the samples. Even so, the difference between countries persisted: the higher the resistance in the incoming wastewater, the higher it remained in the water leaving the plant.

Only at one Portuguese treatment plant did the share of antibiotic resistance genes found in the wastewater grow during purification, turning the plant into an incubator of antibiotic resistance.

Age of treatment plants, water temperature, and other factors have an impact

The study does not provide a direct answer as to why the extent of antibiotic resistance increased in one plant and decreased in the others. The development of resistance may be influenced by a number of factors: the age and size of the treatment plant, the techniques used, the temperature of the wastewater, the amount of antibiotic residue in the water, and the interaction between the bacteria and various types of protozoa found in the water.

"In this study, 11 of the 12 wastewater treatment plants under investigation mitigated the resistance problem, which seems to indicate that modern plants work well in this regard," Marko Virta says.

"At the same time, an older plant or otherwise deficient purification process may end up increasing antibiotic resistance in the environment. We need more research findings from countries with high antibiotic consumption and less developed wastewater treatment practices."

Virta's research group is currently initiating new projects in Asia and West Africa.

Irrigation spreads resistance into food

Assessing the risk associated with antibiotic resistance found in wastewater is difficult, as so far researchers and authorities have an incomplete picture of the number of antibiotic resistance genes potentially causing a clear danger to human health.

At their worst, disease-causing bacteria resistant to antibiotics could be transported in the purified wastewater into the environment and to the irrigation water used in agriculture. Further down the line, they could find their way back to humans in their food.

This problem might particularly impact countries suffering from a lack of potable water since they are more prone to using purified wastewater for irrigation.

More information: K.M.M. Pärnänen el al., "Antibiotic resistance in European wastewater treatment plants mirrors the pattern of clinical antibiotic resistance prevalence," Science Advances (2019). advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/3/eaau9124

Journal information: Science Advances

Provided by University of Helsinki