New research finds a geologic fault system in central Italy that produced a deadly earthquake in 2016 is also responsible for a fifth-century earthquake that damaged many Roman monuments, including the Colosseum. Credit: David Iliff, CC-BY-SA 3.0

A geologic fault system in central Italy that produced a deadly earthquake in 2016 is also responsible for a fifth-century earthquake that damaged many Roman monuments, including the Colosseum, according to new research.

The Mount Vettore fault system, which winds through Italy's Apennine Mountains, ruptured in the middle of the night on August 24, 2016. The magnitude 6.2 earthquake it generated killed nearly 300 people and destroyed several villages in the surrounding region. The fault ruptured again in October 2016, producing two more earthquakes with magnitudes greater than 6.

Scientists had thought the Mount Vettore fault system was dormant until it ruptured in 2016. They knew it could produce earthquakes, but as far as anyone knew, this was the first time the fault had ruptured in recorded history.

But a new study in the AGU journal Tectonics combining geologic data with historical records shows the fault produced a major earthquake in 443 A.D. that damaged or destroyed many well-known monuments from Roman civilization.

Among the damaged buildings were the Colosseum, made famous by the Roman Empire's gladiator contests, as well as Rome's first permanent theater and several important early Christian churches.

The finding suggests dormant faults throughout the Apennines are a silent threat to Italians and the country's numerous historical and cultural landmarks, according to the authors. Quiescent faults could be more destructive than active faults, because researchers don't fully consider them when evaluating seismic hazards, said Paolo Galli, a geophysicist at Italy's National Civil Protection Department in Rome and lead author of the new study.

The surface of the Mount Vettore fault system, where it ruptured in 2016. Credit: Paolo Galli

Reconstructing Italy's geologic past

Italy lies on the southern end of the Eurasian tectonic plate, close to where it meets the Adriatic, African, and Ionian Sea plates. The movement of these plates relative to each other created the Apennine mountains millions of years ago, and makes Italy seismically and volcanically active today.

Hundreds of kilometers of geologic faults snake through the Apennine Mountains. Seismologists consider some of these faults to be silent or dormant because they haven't been linked to any known historical earthquakes.

Scientists thought Mount Vettore was one of these silent fault systems until it ruptured in 2016. After Galli and his colleagues mapped the fault's rupture in 2016, they decided to look for evidence of it having ruptured in the past.

A recently reassembled epigraph, or stone inscription, of the prefect Rufius Caecina Felix Lampadius, describing restorations for the Colosseum after the 443 A.D. earthquake. Credit: Paolo Galli

To do so, they dug deep trenches around parts of the fault system that ruptured in October 2016. The trenches allowed them to see the various sediment layers on either side of the fault and to determine whether the two sides of the fault had moved relative to each other at any other times in the past – in other words, if the fault had generated past earthquakes.

In the new study, Galli and his colleagues analyzed the sediment layers in the trenches and found the Mount Vettore system ruptured five other times in the past 9,000 years, in addition to 2016. One of those ruptures occurred in the middle of the fifth century, at the very end of the Roman period. Averaging the time between ruptures, they found the Mount Vettore system produces major earthquakes every 1,500 to 2,100 years.

Combining science and history

Using data from past archaeological digs in Italy and historical records from the Roman Empire, Galli and his colleagues matched the fifth-century rupture of Mount Vettore to an earthquake that rocked central Italy in 443 A.D., just three decades before the final Roman emperor was deposed.

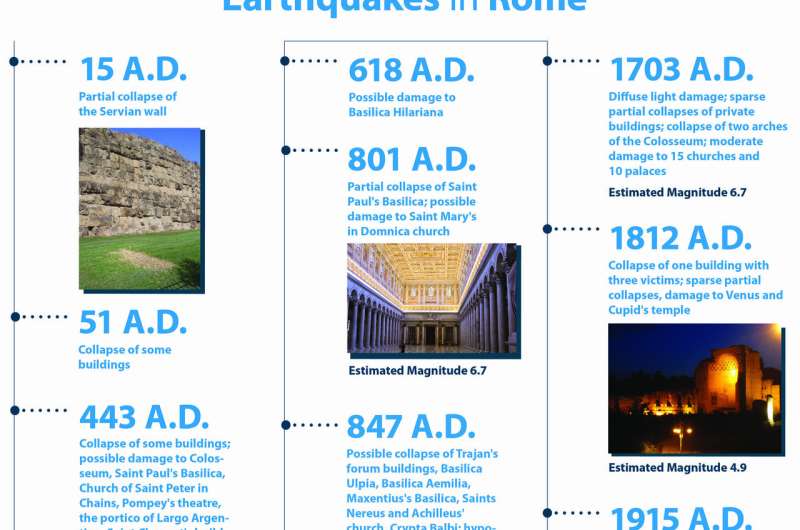

A timeline of past earthquakes that have damaged Roman ruins during the common era (A.D.). Credit: GeoSpace

The 443 earthquake destroyed many towns in the Italian countryside and damaged numerous landmarks in Rome, including the Colosseum and the Theater of Pompey, Rome's first permanent theater. The earthquake also damaged several famous early Christian churches, such as Saint Paul's Basilica and the Church of Saint Peter in Chains, currently home to Michelangelo's statue of Moses. Inscriptions written by Pope Leo I, emperors Valentinianus III and Theodosius II in the fifth century refer to restorations made to these structures likely as a result of this earthquake.

The new study's results suggest the 2016 earthquake was not as unexpected as scientists thought, and other Apennine faults considered dormant by scientists may in fact pose a seismic hazard to central Italy. Considering the immense historical and cultural value of Roman ruins in this region, Galli's priority is to better understand the rest of the silent faults on the Italian peninsula.

More information: P. Galli et al. The Awakening of the Dormant Mount Vettore Fault (2016 Central Italy Earthquake, M w 6.6): Paleoseismic Clues on Its Millennial Silences, Tectonics (2019). DOI: 10.1029/2018TC005326

Provided by American Geophysical Union

This story is republished courtesy of AGU Blogs (http://blogs.agu.org), a community of Earth and space science blogs, hosted by the American Geophysical Union. Read the original story here.