Water molecules bound closest to the mineral have a rigid, ice-like structure and cannot move into arrangements that enable chemical reactions. Water molecules farther from the mineral surface have a less constrained, liquid-like structure and can organize to promote reactivity. Credit: Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory

A team of researchers led by PNNL computational scientist Simone Raugei have revealed new insights about how this complex enzyme does its job, finding that the seemingly wasteful formation of hydrogen has an essential purpose. Their paper, "Critical computational analysis illuminates the reductive-elimination mechanism that activates nitrogenase for N2 reduction," was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in November 2018. Raugei's co-authors are Lance Seefeldt, who holds a joint appointment at PNNL and Utah State University, and Brian Hoffman of Northwestern University.

Nitrogenase can convert nitrogen to ammonia at room temperature and atmospheric pressure. Industry, on the other hand, relies on the Haber-Bosch process, a century-old technique using high temperature and pressure. Fossil fuels typically provide the energy for this process, which is why industrial ammonia production alone accounts for more than 1% of the world's total energy-related carbon emissions. Understanding what lends nitrogenase its bond-breaking muscle can lead to new, stimulating ideas for the design of synthetic catalysts to make ammonia.

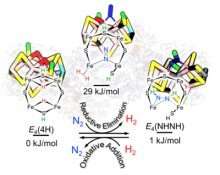

For every molecule of nitrogen transformed to ammonia, nitrogenase makes at least one molecule of hydrogen (H2), which is "one of the most puzzling mysteries of nitrogenase," Raugei said. "Instead of just producing ammonia, you also produce this byproduct. Why is that necessary?"

The researchers found that this phenomenon actually helps nitrogenase tackle nitrogen's strong bonds. "Nature found a solution by coupling the production of hydrogen, which releases energy, with cleaving nitrogen, which requires energy," Raugei said. "It's total balance."

To arrive at the results, the team used a blend of theoretical and experimental methods. Raugei conducted quantum chemical calculations on models of the core of the enzyme, relying on guidance from Seefeldt and Hoffman, who are experts on the biochemistry of nitrogenase. Their experimental data helped inform the computations, and vice versa.

The researchers focused on the nitrogenase catalytic core, composed of iron, molybdenum and sulfur (FeMo-co). During the catalytic event, when FeMo-co has acquired a critical number of electrons and protons (H+) in the form of two bridging hydrides (Fe-H-Fe) in its peripherical belt, generation of an H2 bound to FeMo-co and its displacement by N2 provides the give and take of energy to spark nitrogen reduction, the researchers found.

"We were very well positioned to make to this breakthrough because we combined experimental information on nitrogenase with the computational information," Raugei said. "That was key."

The researchers seek to extend the research by examining the fine details of electron- and proton-accumulation at the active site of nitrogenase and exactly how the N2 bond is broken to form ammonia.

More information: Simone Raugei et al. Critical computational analysis illuminates the reductive-elimination mechanism that activates nitrogenase for N2reduction, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2018). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1810211115

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory