Researchers report nitrate respiration of an enteropathogen

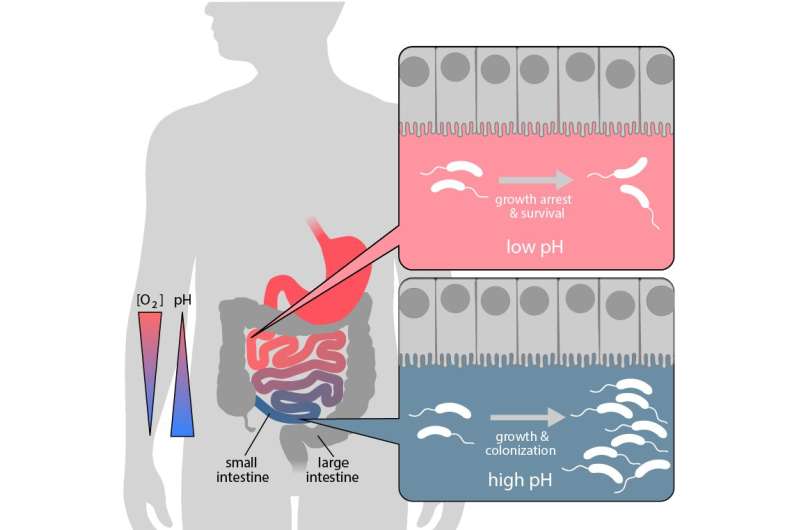

The human pathogen Vibrio cholerae has stumped scientists since its discovery 150 years ago. Experts who studied the bacterium were puzzled that the bacterium was unable to grow under anaerobic conditions although it was equipped with active metabolic machinery to breathe nitrate instead of oxygen, conditions that typically exist in the gastrointestinal tract. The common opinion was that the bacteria accumulates the intermediate product nitrite, which inhibits further growth. The research group of Felipe Cava at the Laboratory for Molecular Infection Medicine Sweden has now studied this bacteria under low-oxygen and varied pH-conditions. Together with their colleagues in Boston, U.S., the scientists at Umeå University discovered an elegant pH-dependent metabolic mechanism that permits the pathogen to switch to a resting mode with preserved viability. The strategy provides a competitive advantage against commensal bacteria to better colonize and infect the intestine. The group have published their results in Nature Microbiology.

To survive and proliferate in the absence of oxygen, many enteric pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae can undergo anaerobic respiration within the host by respiring nitrate instead of oxygen. Respiratory nitrate reduction produces nitrite, a toxic agent, and thus, most nitrate-reducing bacteria normally have additional enzymes to prevent nitrite accumulation. However, Vibrio cholerae accumulates nitrite and stops growth, implying that nitrate respiration could be detrimental for this pathogen. Surprisingly, scientists at Umeå University (Sweden) and their colleagues at Harvard University (USA), have now proved that nitrite is ideal for Vibrio cholerae's lifestyle.

"Nitrate reduction has been reported to be highly induced during infection. We were not convinced that this process could be negative for V. cholerae fitness," said Felipe Cava.

Previous reports showed that under anaerobic conditions, V. cholerae cultures supplemented with nitrate grew less than without nitrate, consistent with the belief that nitrite was toxic. Emilio Bueno and Felipe Cava tested the viability of bacteria and got an unexpected result that changed the project. Bueno, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab, said, "I thought that there should be some kind of technical problem, but I repeated the experiment 10 times with the same results: The viability and growth data were contradictory. We found that, although less grown, V. cholerae cultures supplemented with nitrate fully retained their viability, whereas without nitrate, they were largely dead."

Given that these results proved that nitrite was not responsible of the killing, the team suspected that there was an intriguing mechanism behind this phenomenon. "We found a mutant that survived in the absence of nitrate. This mutant was affected in its fermentative capacity, a pathway that in V. cholerae generates a strong acidification of the media. Therefore, we reasoned that the acidity was the factor compromising Vibrio cholerae's viability, while nitrite's seeming toxicity was inducing a growth arrest state that ultimately prevented the cells from undergoing fermentative suicide," said Bueno.

Remarkably, the authors found that when the pH of the media was higher, Vibrio cholerae was perfectly capable of growing anaerobically with nitrate, and efficiently competed with other bacteria such as intestinal commensals. Given that V. cholerae colonizes the human intestine, which is an anaerobic environment, these results might be particularly relevant during an infection.

The authors observed that these findings are not exclusive of V. cholerae. Similar results were obtained with Salmonella typhimurium, enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) and Citrobacter rodentium.

"It seems that diverse enteric pathogens share the same pH-dependent mechanism to control population expansion and survival in anoxic environments with nitrate. Therefore, our work might inspire the development of new strategies to control gastrointestinal infections and outbreaks. However, the impact of these discoveries might reach far beyond the context of an infection. Therefore, it is important to study whether nitrate-reducing bacteria can benefit from this metabolic switch in the free environment or when associated with other hosts," concludes Felipe Cava.

More information: Emilio Bueno et al, Anaerobic nitrate reduction divergently governs population expansion of the enteropathogen Vibrio cholerae, Nature Microbiology (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41564-018-0253-0

Journal information: Nature Microbiology

Provided by Umea University