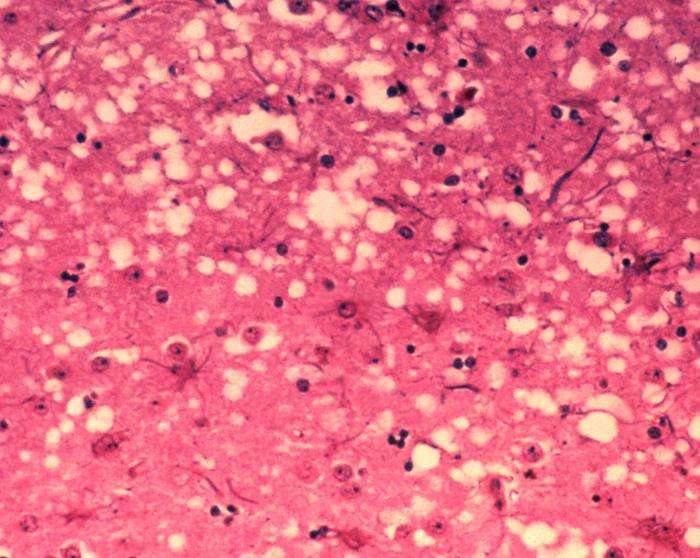

This micrograph of brain tissue reveals the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in bovine spongiform encephalopathy. The presence of vacuoles, i.e. microscopic “holes” in the gray matter, gives the brain of BSE-affected cows a sponge-like appearance when tissue sections are examined in the lab. Credit: Dr. Al Jenny - Public Health Image Library, APHIS: Public domain

Researchers from the Verstreken lab (VIB-KU Leuven) have identified a completely novel function for Hsp90, one of the most common and most studied proteins in our body. In addition to its well-known role as a protein chaperone, Hsp90 stimulates exosome release. These findings shed new light on treatment strategies for both cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

Hsp90, short for heat-shock protein 90, is one of the most abundant proteins, making up one or two out of every hundred proteins in our cells. Heat shock proteins are conserved across animals, plants and even fungi. Their name dates back to the '80, when they were first described as a group of proteins upregulated upon sudden heat stress.

Over the past decades we have learned an awful lot about Hsp90's function. As a protein chaperone, it assists in the proper folding of other proteins and stabilizes them in case of cellular stress. Hsp90 also helps degrade damaged or misfolded proteins that are beyond salvation. These myriad functions make Hsp90 a crucial governor of protein homeostasis in the cell.

Membrane deformation and exosome release

New research by prof. Patrik Verstreken and his team at VIB and KU Leuven shows that—independently of its chaperone function—Hsp90 also aids in the release of exosomes. Exosomes are vesicles that are released from the cell after the fusion of vesicle-containing bodies with the cellular membrane. They can contain signaling molecules but also potentially toxic proteins.

"Our experiments in the lab using fruit flies show that Hsp90 can bind and deform cellular membranes," explains Yu-Chun Wang, one of the researchers in Verstreken's team. "This activity involves a conserved helix structure within Hsp90 that stimulates the fusion of the vesicle-containing bodies with the cell membrane, resulting in the release of exosomes."

What's more, the interaction can be regulated, adds his colleague Elsa Lauwers: "Hsp90 proteins act in pairs, which can take either an open or a closed conformation. Mutations or drugs that stabilize the open conformation allow membrane deformation and thus exosome release, while the closed state blocks both."

Neurodegenerative disease and cancer treatment

According to Prof. Patrik Verstreken, these findings have implications for numerous neurodegenerative diseases. "Exosomes are important for signal transduction across cells, but these vesicles are often hijacked by toxic proteins such as prions, alpha-synuclein or tau, thus contributing to the spread of diseases across the brain." Prions are toxic proteins that cause transmissible brain diseases such as Creutzfeld-Jakob (sometimes referred to as mad cow disease), while alpha-synuclein or tau aggregate in Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease. As such, a better understanding of the mechanisms of exosome release could inform drug development in these areas.

As part of its role as a chaperone, Hsp90 is known to stabilize several proteins that affect tumor growth. That is why Hsp90 inhibitors are currently investigated for cancer therapy. Verstreken's team uncovered that some of these inhibitors may also block exosome release.

"We found that some of the Hsp90 inhibitors that are being developed for clinical use in fact also inhibit exosome release," says Verstreken. "Our work may thus bring important insights into the mode of action of these drugs, and of course their potential adverse effects."

Provided by VIB (the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology)