Study of ancient forefoot joints reveals bipedalism in hominins emerged early

The feet of primates function as grasping organs. But the adoption of bipedal locomotion – which reduces the ability to grasp – was a critical step in human evolution.

In the first comprehensive study of the forefoot joints of ancient hominins, to be published online in PNAS, an international team of researchers conclude that adaptations for bipedal walking in primates occurred as early as 4.4 million years ago, and in that process early hominin feet may have retained some grasping ability.

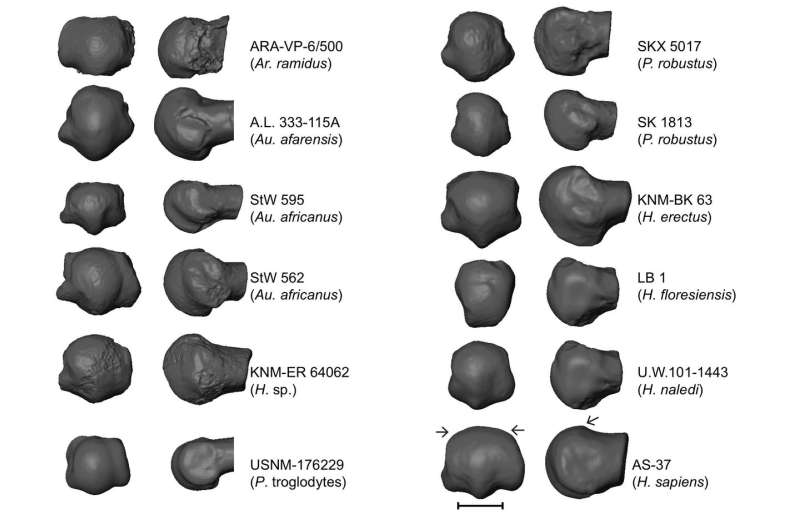

Co-author Carrie S. Mongle, a doctoral candidate in the Interdepartmental Doctoral Program in Anthropological Sciences, explained that by studying and comparing the toe joint morphologies in fossil hominins, apes, monkeys and humans, the researchers identified novel bony shape variables in the forefoot from both extinct to existent hominins that are linked to the emergence of bipedal walking. Included in their paper, titled "Evolution and function of the hominin forefoot," are data that provide evidence for how and when the hominin pedal skeleton evolved to accommodate the unique biomechanical demands of bipedalism.

The findings also corroborate the importance of a bony morphology in hominins called the dorsal head expansion and "doming" of the metatarsal heads – essential for bipedalism and a unique feature that distinguished hominins from other primates.

More information: Peter J. Fernández et al. Evolution and function of the hominin forefoot, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2018). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1800818115

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by Stony Brook University