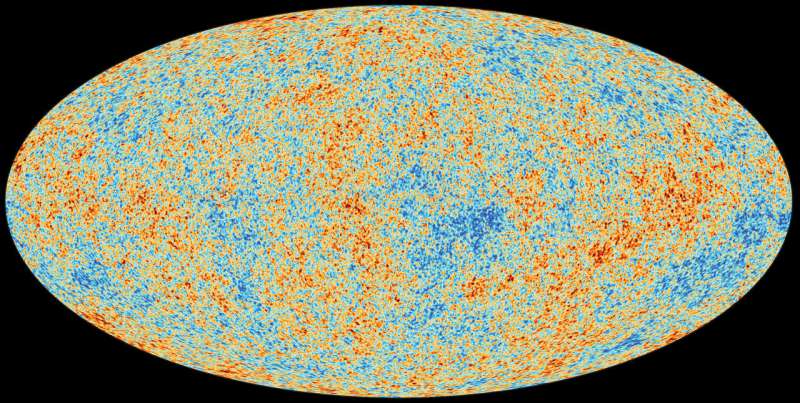

Planck’s view of the cosmic microwave background. Credit: ESA/Planck Collaboration

It was 21 March 2013. The world's scientific press had either gathered in ESA's Paris headquarters or logged in online, along with a multitude of scientists around the globe, to witness the moment when ESA's Planck mission revealed its 'image' of the cosmos. This image was taken not with visible light but with microwaves.

Whereas light that our eyes can see is composed of small wavelengths – less than a thousandth of a millimetre in length – the radiation that Planck was detecting spanned longer wavelengths, from a few tenths of a millimetre to a few millimetres. Most importantly, it had been generated at very beginning of the Universe.

Collectively, this radiation is known as the cosmic microwave background, or CMB. By measuring its tiny differences across the sky, Planck's image had the ability to tell us about the age, expansion, history, and contents of the Universe. It was nothing less than the cosmic blueprint.

Astronomers knew what they were hoping to see. Two NASA missions, COBE in the early 1990s and WMAP in the following decade, had already performed an analogous set of sky surveys that resulted in similar images. But those images did not have the precision and sharpness of Planck.

The new view would show the imprint of the early Universe in painstaking detail for the first time. And everything was riding on it.

If our model of the Universe were correct, then Planck would confirm it to unprecedented levels of accuracy. If our model were wrong, Planck would send scientists back to the drawing board.

Operating between 2009 and 2013, ESA’s Planck mission scanned the sky at microwave wavelengths to observe the cosmic microwave background, or CMB, which is the most ancient light emitted in the history of our Universe. Data from Planck have revealed an ‘almost perfect Universe’: the standard model description of a cosmos containing ordinary matter, cold dark matter and dark energy, populated by structures that had been seeded during an early phase of inflationary expansion, is largely correct, but a few details to puzzle over remain. In other words: the best of both worlds. Credit: ESA/Planck Collaboration

When the image was revealed, the data had confirmed the model. The fit to our expectations was too good to draw any other conclusion: Planck had showed us an 'almost perfect Universe'. Why almost perfect? Because a few anomalies remained, and these would be the focus of future research.

Now, five years later, the Planck consortium has made their final data release, known as the legacy data release. The message remains the same, and is even stronger.

"This is the most important legacy of Planck," says Jan Tauber, ESA's Planck Project Scientist. "So far the standard model of cosmology has survived all the tests, and Planck has made the measurements that show it."

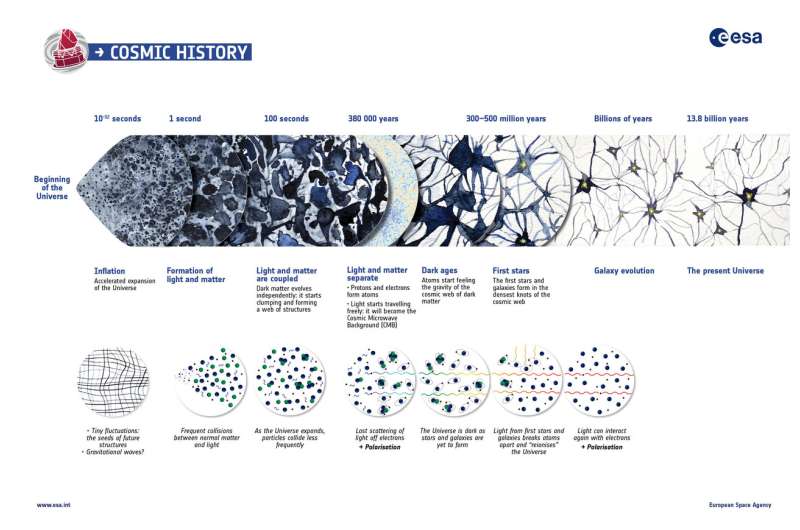

All cosmological models are based upon Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity. To reconcile the general relativistic equations with a wide range of observations, including the cosmic microwave background, the standard model of cosmology includes the action of two unknown components.

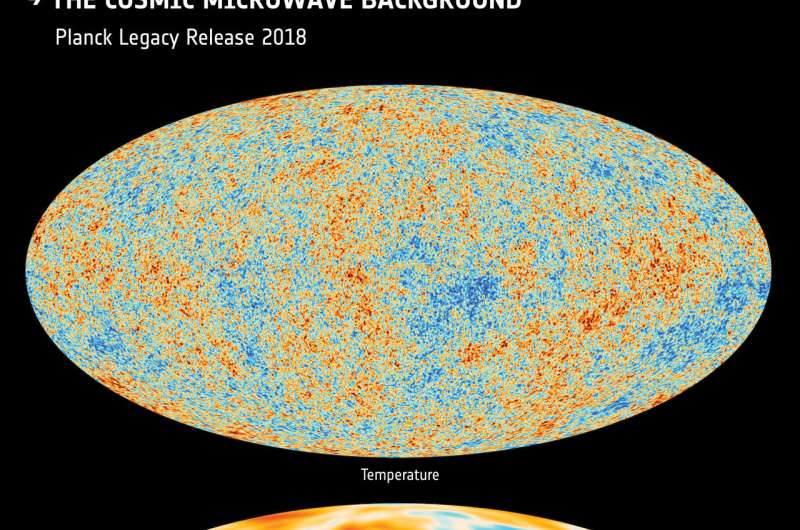

The Cosmic Microwave Background: temperature and polarisation. Credit: ESA/Planck Collaboration

Firstly, an attractive matter component, known as cold dark matter, which unlike ordinary matter does not interact with light. Secondly, a repulsive form of energy, known as dark energy, which is driving the currently accelerated expansion of the Universe. They have been found to be essential components to explain our cosmos in addition to the ordinary matter we know about. But as yet we do not know what these exotic components actually are.

Planck was launched in 2009 and collected data until 2013. Its first release – which gave rise to the almost perfect Universe – was made in the spring of that year. It was based solely on the temperature of the cosmic microwave background radiation, and used only the first two sky surveys from the mission.

The data also provided further evidence for a very early phase of accelerated expansion, called inflation, in the first tiny fraction of a second in the Universe's history, during which the seeds of all cosmic structures were sown. Yielding a quantitative measure of the relative distribution of these primordial fluctuations, Planck provided the best confirmation ever obtained of the inflationary scenario.

Besides mapping the temperature of the cosmic microwave background across the sky with unprecedented accuracy, Planck also measured its polarisation, which indicates if light is vibrating in a preferred direction. The polarisation of the cosmic microwave background carries an imprint of the last interaction between the radiation and matter particles in the early Universe, and as such contains additional, all-important information about the history of the cosmos. But it could also contain information about the very first instants of our Universe, and give us clues to understand its birth.

The history of the Universe. Credit: European Space Agency

In 2015, a second data release folded together all data collected by the mission, which amounted to eight sky surveys. It gave temperature and polarisation but came with a caution.

"We felt the quality of some of the polarisation data was not good enough to be used for cosmology," says Jan. He adds that – of course – it didn't prevent them from doing cosmology with it but that some conclusions drawn at that time needed further confirmation and should therefore be treated with caution.

And that's the big change for this 2018 Legacy data release. The Planck consortium has completed a new processing of the data. Most of the early signs that called for caution have disappeared. The scientists are now certain that both temperature and polarisation are accurately determined.

"Now we really are confident that we can retrieve a cosmological model based on solely on temperature, solely on polarisation, and based on both temperature and polarisation. And they all match," says Reno Mandolesi, principal investigator of the LFI instrument on Planck at the University of Ferrara, Italy.

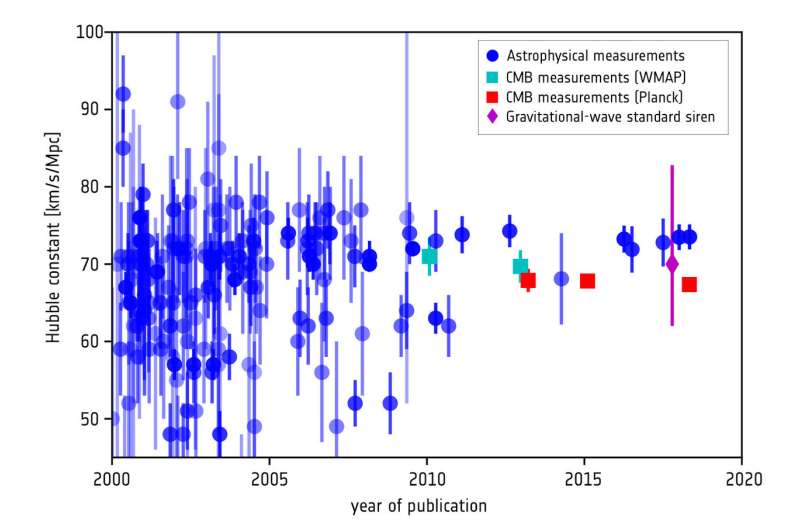

Measurements of the Hubble constant. Credit: ESA/Planck Collaboration

Provided by European Space Agency