The highly complex sugarcane genome has finally been sequenced. Credit: R. Carayol

Sugarcane was the last major cultivated plant to have its genome sequenced. This was because of its huge complexity: The genome comprises between 10 and 12 copies of each chromosome, while the human genome has just two. It was an international team coordinated by CIRAD that achieved this milestone, as reported in Nature Communications on July 6. It will now be possible to modernize the methods used to breed sugarcane varieties. This will be a real boon to the sugar and biomass industry.

Sequencing the sugarcane genome was so complex that conventional sequencing techniques proved useless. This meant that sugarcane was the last major cultivated plant to have its genome sequenced.

The team took up the gauntlet using a new approach based on a discovery made at CIRAD some 20 years previously: The genome structures of sugarcane and sorghum are very similar. The term for this is "collinearity," which means that there is a degree of parallelism, with numerous genes occurring in the same order. Olivier Garsmeur, a CIRAD researcher and lead author of the study, was thus able to use the sorghum genome as a template to assemble and select the sugarcane chromosome fragments to sequence. "Thanks to this novel method, the reference sequence obtained for a cultivar from Réunion, R570, is very good quality," says Angélique D'Hont, a CIRAD geneticist who coordinated the study.

That reference sequence is a vital step toward fully sequencing the sugarcane genome and analysing the variations between the various sugarcane varieties more effectively. Angélique D'Hont had the same experience with the banana genome in 2012. She says, "having a reference sequence for a species radically changes all the genomic and more broadly genetic approaches for that species."

As with all other cultivated plants before it, sugarcane breeding will now be able to enter the age of molecular biology. Until now, for want of a reference sequence, sugarcane cultivar breeding programmes were restricted to hybridization, followed by cumbersome conventional field assessments. Molecular screening techniques can now be developed to supplement field trials. This is a major breakthrough, since almost 80 percent of the world's sugar comes from sugarcane. Moreover, the plant has also recently become a biomass crop. This new genetic knowledge will serve to create new varieties for a wider range of uses.

Credit: CIRAD

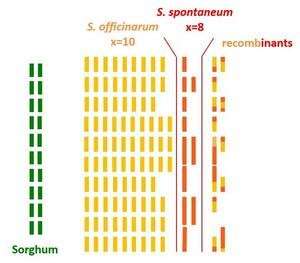

In comparison to sugarcane, the sorghum genome (in green) is much simpler. Each bar represents a sugarcane chromosome. In orange, those from a domesticated variety, Saccharum officinarum , and in red, those from the wild variety S. spontaneum.

The sugarcane genome is complex for several reasons:

- high polyploidy (large number of copies of each chromosome category)

- aneuploidy (variable number of copies depending on the chromosome category)

- bispecific origin of the chromosomes

- structural differences and interspecific chromosome recombinants.

More information: Olivier Garsmeur et al, A mosaic monoploid reference sequence for the highly complex genome of sugarcane, Nature Communications (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05051-5

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by CIRAD