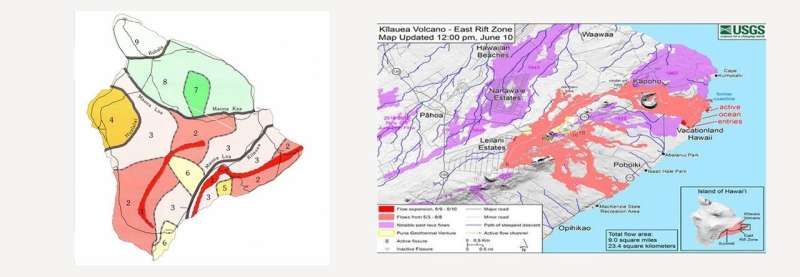

Detail of map on left shows lava-flow hazard zones on the island of Hawaii as determined by Thomas Wright and the U.S. Geological Survey in 1992 (ranked in descending order with nine being least hazardous and one being most hazardous); map on right shows lava flow as of June 10. Credit: U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY / U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

In the late 1980s, geologist Thomas Wright oversaw the production of a volcano hazard map that would help guide zoning and land use decisions on the island of Hawaii.

The map, published in 1992 by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, featured two bright red ridges running along volcanoes Mauna Loa and Kilauea on the island's southeast quadrant. Red crosshatching ran from the ridge line to the coast, marking the most hazardous areas for real estate development.

Housing developments were built anyway, said Wright during a talk Tuesday at Johns Hopkins University. He had even recently been invited to give a concert with his string quartet in a gated community built along the shore in the hazard zone he had identified decades before.

"Politicians don't want to take land out of circulation," he said. "Hazard maps and land use are always politically fraught."

Last month, following a 6.9-magnitude earthquake on the island, Kilauea erupted, spewing projectile rocks and debris and sending lava streaming down the island's ridges. By May 17, two weeks after the eruption, plumes of steam and volcanic ash reached nearly six miles into the air.

Officials report that more than 700 homes in the area have been destroyed by lava flows, which have also created environmental health emergencies, Wright said. Along the shoreline, as lava pours into the ocean, it mixes with the saltwater, forming clouds of hydrochloric acid—which Wright called lava haze, or laze. On roadways, otherworldly blue flames leap from cracks in the pavement where lava has ignited leaking methane gas.

A new fissure erupted in the evening of May 5, beginning with small lava spattering at about 8:45 p.m. local time. By 9 p.m., lava fountains as high as 230 feet erupted from the fissure. Credit: U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY / U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Wright, a Johns Hopkins alum who has worked for the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory and the U.S. Geological Survey, said he didn't expect the volcanic eruption to end any time soon.

"I think it's most likely that there will be a long-term extension of activity," he said. "There have been ongoing explosions and earthquakes, and historically, activity at Kilauea has been linked to activity at Mauna Loa, so we really don't know what the future is."

He added: "Kilauea is potentially, in my view, one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world."

Wright spoke Tuesday as part of the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences' 50th anniversary symposium. The department was established in 1968 when the Krieger School's departments of oceanography and geology merged. As the department celebrates its milestone anniversary, it also ushers a new phase of leadership.

"This department has gone through an almost total refresh," said Anand Gnanadesikan, an oceanographer and climate modeler who will succeed Thomas Haine as chair of the department this summer. "In the past seven years, we've hired nine new tenure-track faculty members and one teaching-track faculty member. We really planned this symposium to help highlight the work of our junior faculty and give them a chance to highlight what they're excited about going forward."

Provided by Johns Hopkins University