Neanderthals are thought to have needed up to 4,480 calories a day to keep them alive in the European winter—some of their skulls have been on display as part of a Neanderthal exhibition at the Musee de l'Homme in Paris since last month

Neanderthals had large, protruding noses to warm and humidify cold, dry air, a study into the distinct design of our extinct European cousin's face suggested Wednesday.

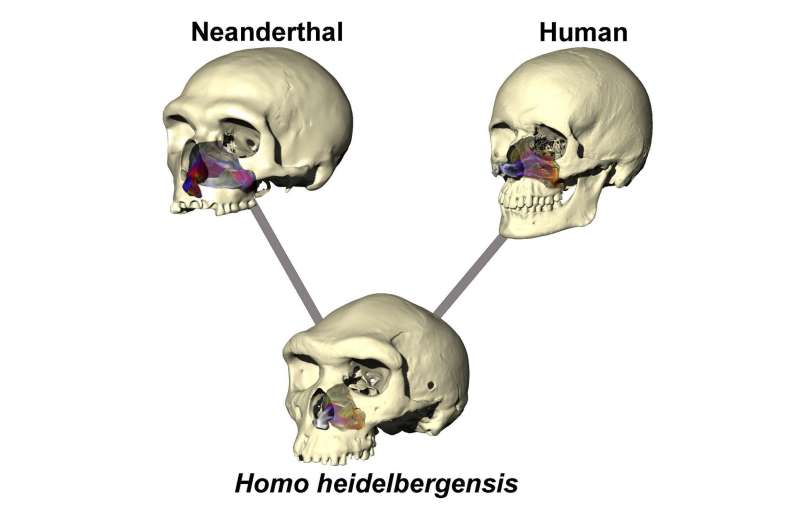

Using 3-D models of the skulls of Neanderthals, modern humans, and Homo heidelbergensis—considered to have been the common ancestor of both—an international research team found very different breathing adaptations.

Computerised "fluid dynamics" revealed that the shape of Neanderthal and human faces "condition air more efficiently" than H. heidelbergensis, suggesting that "both evolved to better withstand cold and/or dry climates," the researchers wrote in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

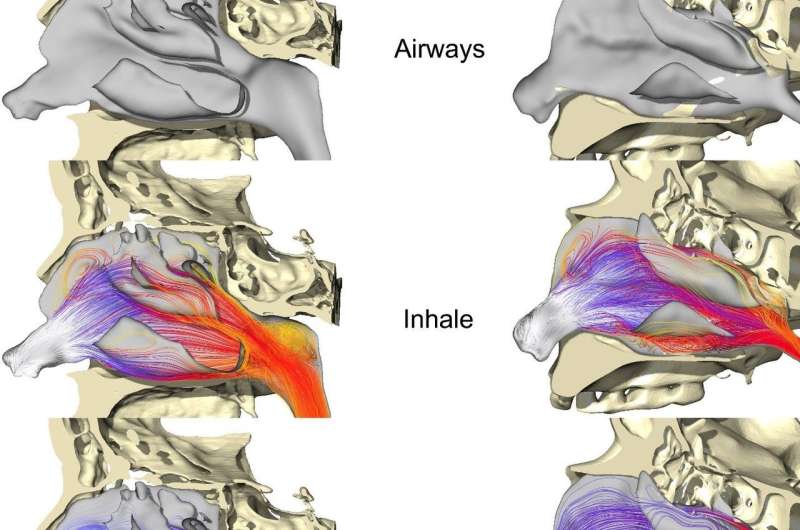

Neanderthals could also move "considerably more" air through their nasal cavity than could H. heidelbergensis or modern humans—possibly in response to higher energy requirements for their stocky bodies and hunting lifestyle.

Neanderthals were thought to have required as much as 4,480 calories per day to keep them alive in the European winter. For a modern human male, 2,500 daily calories are recommended.

A high-calorie intake requires more oxygen to burn the sugars, fats and proteins in our cells to produce energy.

Take a deep breath

Scientists have long debated over the reason for the Neanderthal's face shape, which includes a large, wide nose and protruding upper jaw.

One theory was they were built to exert more bite force.

But Wednesday's study said this was not the case. Computer simulations showed that Neanderthals "were not particularly strong biters" compared to humans.

Image illustrates the difference in skull and nose shape in the three human species tested. Airflow is color-coded for temperature (warmer colors = warmer air, cooler colors = colder air). Lines indicate that Neanderthal and modern-humans likely diverged from an ancestor very close to Homo heidelbergensis. Credit: University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales

But "where the Neanderthal really excelled is in its ability to move large volumes of air through its nasal passage, indicating a very high-energy lifestyle."

The conclusion, said the team, was "that the distinctive facial morphology of Neanderthals has been driven, at least in part, by adaptation to cold"—both to "condition" cold, dry air, and to absorb more oxygen.

Airflow comparison between a modern human (left) and Neanderthal (right) when breathing in air at 0°C (32°F), with warmer colors representing warmer air flow and cooler colors representing colder air flow. Skulls have been cut down the midline to better visualize the airway. As demonstrated, Neanderthals were better suited to condition large amounts of cold air than today's humans. Credit: University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales

Neanderthals emerged in Europe, Central Asia and the Middle East some 200,000 years ago. They vanished about 30,000 years ago—coinciding with the arrival of modern humans out of Africa.

The two groups briefly overlapped and interbred, and today, non-African people are said to carry about 1.5-2.1 percent of Neanderthal DNA.

Long portrayed as knuckle-dragging brutes, recent studies have started to paint a picture of Neanderthals as sophisticated beings who made art, took care of the elderly, buried their dead, and may have been the first jewellers—though they were probably also cannibals.

More information: Computer simulations show that Neanderthal facial morphology represents adaptation to cold and high energy demands, but not heavy biting, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, rspb.royalsocietypublishing.or … .1098/rspb.2018.0085

Journal information: Proceedings of the Royal Society B

© 2018 AFP