Credit: Monash University

There's no shortage of global issues. Nuclear tensions, increasing drug use, genocide in Syria, mass shootings, extreme weather events, animals going extinct, obesity ... these are only a few on an almost endless list.

On some we can all agree; others are more controversial. Take Donald Trump's presidency – some denounce him as a divisive misogynist who puts the country and the world at risk, while others hail him for addressing the needs of the average American, bringing down bureaucracy and reviving the economy.

Some are so controversial that they hang around for decades, Take marriage equality in Australia. The Netherlands settled on this issue in 2000, but it took Australia 17 more years to achieve it.

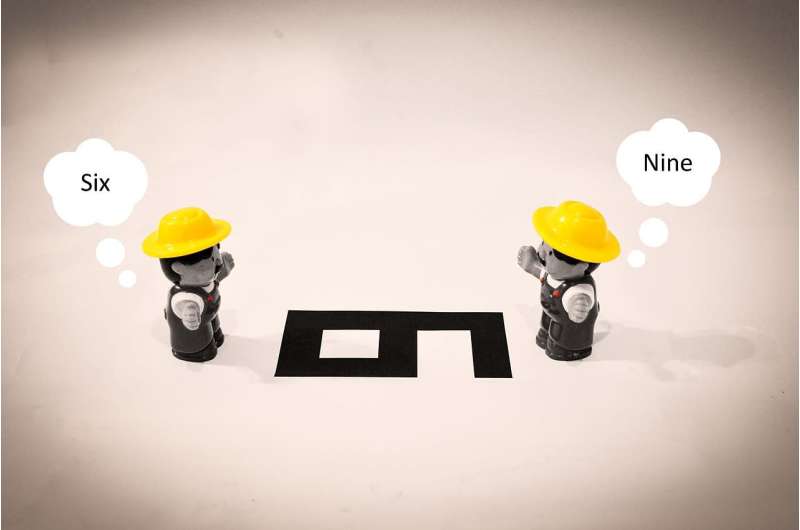

So what makes issues controversial, why can it take so long to address them, and why are they often so divisive? Well, it has much to do with how we learn.

We often approach controversial issues like we approach riding a bike – without thinking. Balancing, pedalling, steering, paying attention to traffic ... riding a bike is surprisingly complex. But after much practice we can a ride bike and do all these things while thinking about what we will have for dinner that night.

Becoming really good at something includes a move from conscious to unconscious thinking and acting. Through practice and reflection, we 'program' our brain, and as a result we don't have to think about all this complexity every time we ride a bike. It certainly makes life easy and exemplifies that practice makes perfect.

This programming starts at a very early age. Slowly we learn to navigate social situations, we learn practical skills and obtain ideas and values through family and political, religious, and other social circles. Over time, all this practice shapes our deepest values and beliefs and hones skills. Interestingly, we're not aware of much of what we've learned because we were either too young to remember or the process was too gradual to realise. Learning makes us all unique, but also determines how we see and approach controversial issues.

It probably comes as no surprise that we find it easier to agree with something that aligns with our values and beliefs than to something that does not, regardless of whether it's right or not. Because we better understand information that aligns with our values and beliefs, it's also easier to recall or interpret such information.

Researchers refer to this phenomenon as 'confirmation bias'. For example, when asked to draw an 'effective leader', most people will draw a man. We perpetuate the idea of effective leaders being men after being trained by many images of male leaders in movies, advertising and elsewhere. A good illustration is that Google for a long time portrayed men in 77 per cent of its Doodles (image on the homepage) until it recognised this bias and purposefully changed it to represent males and females equally in 2014.

Abraham Maslow, a psychologist and management guru, said: "I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail." Which means that you approach controversial issues with your unique values, beliefs, and skills – your hammer.

In other words, people trained as, for example, engineers will try to engineer their way out of every problem because they are familiar and comfortable with the beliefs and assumptions of that skill set.

Unfortunately, many of the issues I mentioned at the start of this article are too complex to solve with just a hammer. They need a whole toolbox, and more importantly, the tools need to know how to understand each other and work together.

Credit: Monash University

Now back to controversial issues. Last week, Monash University released a video that came with a trigger warning: "Some may find the following disturbing."

The video starts with a cascade of big issues, very similar to the list at the top of this article. Not surprisingly, this video generated plenty of reactions that together can illustrate how our biases dictate how we relate to those issues.

Take the opening shot – a left-wing protester elbows alt-right figurehead Richard Spencer. Based on your values and beliefs, you might support the left-wing protester, or you might support Spencer and blame the protester or altogether see it is an example of how violence is threatening free speech.

Yaysayers and naysayers of climate change can view a polar bear on an iceberg and images of extreme weather events as driving a climate change agenda, or as disturbing images of a threatened species and extreme weather events, full stop. You might like it, or not.

Because everyone views these issues through their unique lens, everyone's opinion on these issues is unique, as are their approaches. It therefore doesn't matter what your take on these issues is, but more so how you respond to them.

Big issues become controversial because they touch on our deepest values and beliefs, regardless of whether we're for or against, or what is right or wrong. The closer to our core, the stronger and often more emotional, or even physical this reaction becomes, to the extent that people elbow others for their views, leave disturbing comments online, or feel sick watching Trump or hear others speak about climate change.

My point is therefore not to convince you one way or the other. My point is that every time we're confronted with issues and viewpoints that don't align with our values and beliefs, it evokes a reaction. It makes us want to hang on to our beliefs more strongly, because changing these beliefs would be changing ourselves.

Because our beliefs and values define us, as well as our closest social circles, we respond strongly to others with different values. It becomes an 'us-versus-them' situation, as we start to stereotype 'them' as a group – left activists, climate deniers, Muslims, Aboriginals.

We denounce their values and look down on them. How could they possibly think X or believe Y!

We think of them as dumb, less worthy of our attention, and we might even despise them. If they happen to respond to our viewpoints, our biases seek further confirmation on what we already think about them, and vice versa. This can generate a cycle of destructive criticism, which can take decades to resolve.

What is your tool of preference, and how will you use it when you come across a controversial issue? Your views are essential, and criticism is great. They keep the conversation alive about what needs to be changed, in what pace, and by whom. It creates a clash of value systems, which elicits emotions and a drive to either step-up or defend, which are both honourable actions.

While you may not be able to choose your initial emotions, you can choose how you react and contribute. Can you change destructive criticism into constructive criticism and drive progress on controversial issues, together with all the other tools?

Provided by Monash University