February 14, 2018 report

Silent singing crickets still going through the motions

A team of researchers with the University of St Andrews and the University of Cambridge, both in the U.K., has found that singing crickets in Hawaii have evolved to silence their singing apparatus but continue to sing inaudibly. In their paper published in the journal Biology Letters, the group describes their study of field crickets living on the island of Kauai and suggest some possibilities for the behavior they witnessed.

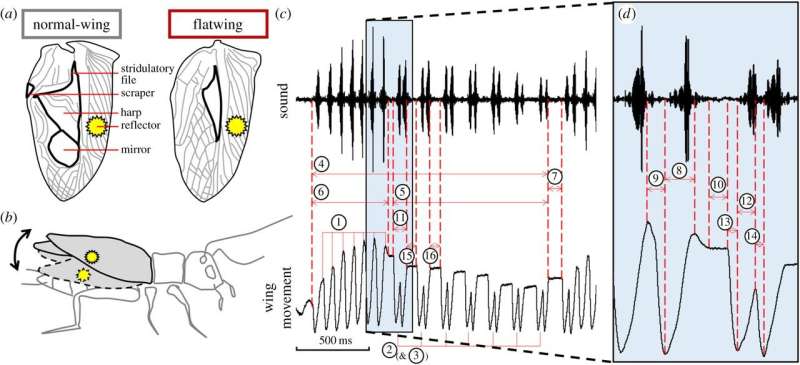

Most field crickets rub their wings together to produce a singing sound in order to attract a mate. But the field crickets on Kauai found themselves under attack many years ago—parasitic flies attracted by their singing began using them as hatcheries for their young, and the larvae would eat them from the inside out. Because of that, evolution took over, causing changes to the wings that prevented sounds when they were rubbed together, and the crickets went silent. However, the researchers found that they did not stop trying to sing—they still rub their wings together, singing in silence like sad mimes.

To better understand what was occurring, the researchers brought samples into their lab and photographed and recorded them and then analyzed their data. They found that despite being unable to make any noise with their wings, the males continued to rub them together.

Among crickets in the field, the researchers found that muted males moved closer to cricket varieties that still sing, using the song of another male to capture the attention of a potential mate. The researchers were not able to identify a mating strategy in areas where all the males were mute, suggesting they may have evolved another mating behavior that has not yet been observed.

The team reports that they plan to continue studying the crickets. They want to know if the silent wing rubbing is lessening—a sign that evolution is making it obsolete or if the continued rubbing is serving another purpose. The researchers are also interested in what has happened with other behaviors related to singing, such as warning off other males both before and after mating.

More information: Will T. Schneider et al. Vestigial singing behaviour persists after the evolutionary loss of song in crickets, Biology Letters (2018). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2017.0654

Abstract

The evolutionary loss of sexual traits is widely predicted. Because sexual signals can arise from the coupling of specialized motor activity with morphological structures, disruption to a single component could lead to overall loss of function. Opportunities to observe this process and characterize any remaining signal components are rare, but could provide insight into the mechanisms, indirect costs and evolutionary consequences of signal loss. We investigated the recent evolutionary loss of a long-range acoustic sexual signal in the Hawaiian field cricket Teleogryllus oceanicus. Flatwing males carry mutations that remove sound-producing wing structures, eliminating all acoustic signalling and affording protection against an acoustically-orientating parasitoid fly. We show that flatwing males produce wing movement patterns indistinguishable from those that generate sonorous calling song in normal-wing males. Evolutionary song loss caused by the disappearance of structural components of the sound-producing apparatus has left behind the energetically costly motor behaviour underlying normal singing. These results provide a rare example of a vestigial behaviour and raise the possibility that such traits could be co-opted for novel functions.

Journal information: Biology Letters

© 2018 Phys.org