Scientists shed light on new low-cost material for seeing in the dark

Scientists at the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and Stony Brook University have developed a new synthesis process for low-cost fabrication of a material previously discounted in literature for high-sensitivity infrared cameras, opening new possibilities for future Army night-time operations.

ARL's Drs. Wendy Sarney and Stefan Svensson led a novel approach to using the semiconductor InAsSb, a material that has not been used before in high-performance IR cameras for the longest wavelengths (10 micron). The best materials for the IR camera light-sensors are currently based on HgCdTe, which belongs to the family of II-VI compounds.

"Unfortunately, they are very expensive, mostly because there are only military customers for this material," Svensson said.

InAsSb is a III-V semiconductor, which is a class of materials used in opto-electronics in many commercial products such as DVD players and cell phones.

"The human eye is optimized by nature to observe reflected light from the sun in a very narrow band of colors (wavelengths of light), known as the visible spectrum; however, all objects in nature glow with a faint light even at low temperatures, which produces colors in the infrared (IR) range which are invisible to the naked eye. These wavelengths are about ten times longer than those of visible light.

"By using cameras that can see the faint IR light, soldiers can operate during night times," Sarney said. "The more sensitive such a camera is, or in other words, the smaller the color or temperature differences are that it can see, the more details that can be discerned on a battlefield and enemies can be detected at longer ranges. High-performance IR cameras are therefore extremely important for the Army."

The key in this discovery was the realization that the material needed to be undistorted by strain in order to see at 10 microns. This was a major difficulty that had to be overcome before InAsSb could be used as a sensor material. The performance of devices based on semiconductor materials also depends on the material's crystalline perfection. InAsSb has to be deposited onto a starting crystalline material (a substrate) which has a smaller spacing between the atoms. This size mismatch at the atomic scale must be managed extremely well in order for the light-sensitive material to work properly.

Among possible substrates, larger and cheaper ones typically have progressively smaller atomic spacing. Over several years ARL and Stony Brook found a way to manage the atomic spacing mismatch culminating in the current work which uses GaAs as a substrate. This is the most common substrate used in the III-V industry for numerous consumer products. It is inexpensive and available in large sizes. Large area substrates allows manufacturing of multiple camera sensors at the same time which could be done in commercial foundries. All this opens opportunities to produce high-quality IR cameras for soldiers at a much reduced cost.

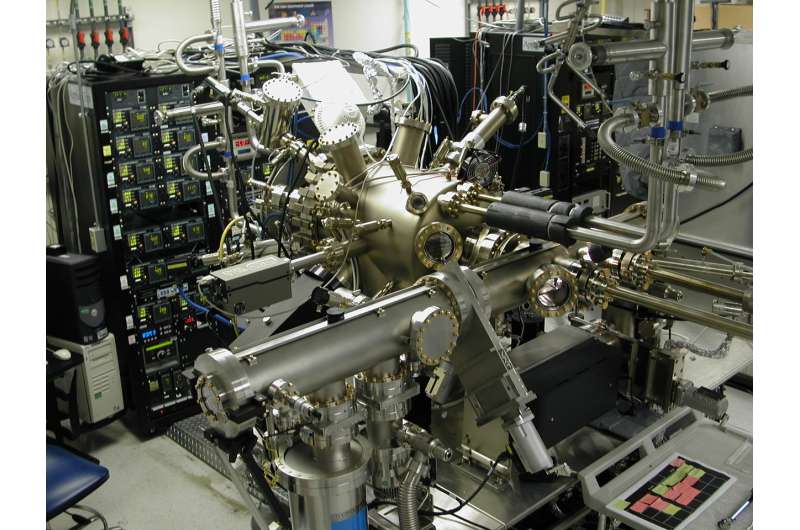

ARL and Stony Brook combined strain-mediating techniques to effectively manage the ?10% atomic spacing mismatch between the InAsSb sensing material and GaAs substrate. To do this, they deposited an intermediate layer of GaSb onto GaAs in a way that trapped most of the defects caused by the size mismatch. They then further increased the atomic spacing with a graded layer that also kept defects away from the InAsSb sensor material.

The material was examined with high resolution transmission electron microscopy in order to make sure it had sufficient structural quality. They also found that the optical quality related to detection properties was remarkably high. This research shows a path to a practical, lower cost solution for the eventual fielding of night-vision systems based on III-V long wavelength infrared materials.

Provided by U.S. Army Research Laboratory