Lab-made hormone may reveal secret lives of plants

A lab-designed hormone may unlock mysteries harbored by plants.

By developing a synthetic version of the plant hormone auxin and an engineered receptor to recognize it, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Investigator Keiko Torii and colleagues are poised to uncover plants' inner workings.

The new work, described January 22, 2018, in the journal Nature Chemical Biology, is "a transformative tool to understand plant growth and development," says Torii, a plant biologist at the University of Washington. That understanding may have big agricultural implications, raising the possibility, for instance, of a new way to ripen strawberries and tomatoes.

To plants, the hormone auxin is king. Among many other jobs, auxin helps sunflowers track sunlight, roots grow downward, and fruits ripen. This wide range of jobs, as well as the fact that every cell in a plant can both produce and detect auxin, makes it tricky to tease apart the hormone's various roles. "It's been a huge mystery as to how such a simple molecule can do so many different things," Torii says.

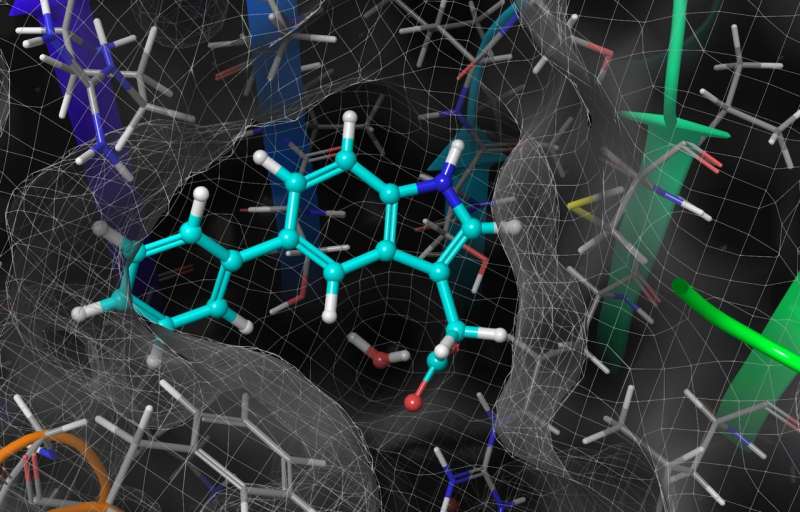

She and her colleagues set out to create a new way to study plants' responses to auxin by designing a lab-made version of the hormone that can be precisely controlled. Working with synthetic chemists in Japan, the researchers added a little bump to auxin's structure—hydrocarbon rings that auxin doesn't normally contain. The researchers then tweaked plants' auxin receptor, a protein that sits on the outside of plant cells and detects auxin. This time, the researchers removed a bulky amino acid from the receptor, creating a perfect-sized hole that cradles the lab-made auxin. That simple switch, called a "bump and hole" strategy, "is really elegant, actually," Torii says.

Next, the researchers tested whether this matched set—the synthetic auxin and the synthetic receptor—could do the same jobs as the cells' natural auxin/receptor pair. The intricately designed system worked beautifully, experiments on roots showed.

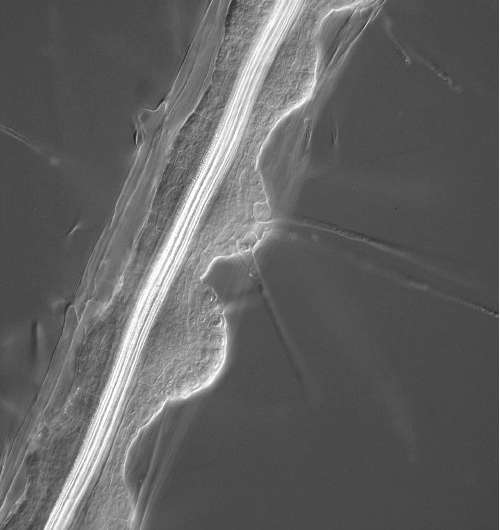

Normally, roots exposed to auxin stop growing down, and instead grow sideways by activating stem cells that break out of the main root. Torii compares the process, called lateral root development, to aliens bursting through stomachs. After detecting synthetic auxin, Arabidopsis plants genetically engineered to produce the synthetic auxin receptor behaved just like normal - growing the same sideways baubles of root branches.

What's more, roots that didn't have the synthetic auxin receptor were essentially "blind" to synthetic auxin, proof that the artificial hormone is detected by only the artificial receptor. Torii and her colleagues call this switch to synthetic auxin "chemical hijacking"—a well-controlled takeover that will now allow researchers to tease apart the tangled web of auxin's jobs in plants.

With their system up and running, the researchers tested a long-standing question in plant biology. Scientists knew that germinating seedlings use auxin to grow quickly. But the identity of the exact receptor that allows this process to happen wasn't settled.

The scientific community had a suspect in mind. Torii's team produced a plant that lacked an auxin receptor called TIR1, and instead possessed a synthetic version. When exposed to artificial auxin, these seedlings began to grow rapidly, behaving exactly as if they had the normal receptor. The results suggest that seed elongation does indeed happen through the TIR1 receptor.

Other fundamental scientific questions can be addressed with this system, Torii says, such as auxin's role in corn ripening and in opening the stomata, the structures that let plants breathe.

One day, synthetic auxin might even find a place in agriculture. Auxin is currently sprayed on fruits to hasten ripening. But in high concentrations, the hormone can act as a plant-killing herbicide. Fruits engineered to carry the synthetic receptor could be ripened with the synthetic auxin hormone, Torii says, eliminating the need to spray auxin indiscriminately. But, she cautions, much more testing needs to be done before a synthetic hormone system can be used for growing food.

More information: Naoyuki Uchida et al. "Chemical hijacking of auxin signaling with an engineered auxin-TIR1 pair." Nature Chemical Biology. Published online January 22, 2018. DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.2555

Journal information: Nature Chemical Biology

Provided by Howard Hughes Medical Institute